The world wants to pay America to use the dollar. We should let them.

Owning the world's reserve currency is a privilege — and a responsibility

Glance in a Walmart, and one immediately realizes that Americans buy a ton of foreign-made stuff. Though the U.S. manufacturing sector produces much more than is commonly believed, we still import quite a bit more than we export. This is the source of the notorious trade deficit, which has been a thorn in the American side for decades.

For an ordinary country, this would be a serious problem. Imports exceeding exports typically means either a run-up in borrowing, or spending down foreign currency reserves. Keep that up for too long, and crisis will eventually strike.

However, the U.S. is not an ordinary country, as economist J.W. Mason explains in a brilliant paper for the Roosevelt Institute. Our trade deficit is in large part a result of the fact that the dollar is used as the world's reserve currency — and that gives the U.S. a much larger capacity to carry a trade deficit. Essentially, the world wants to pay us to use dollars. We should let them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I have written before about John Maynard Keynes' idea to construct an institution to manage international currency and trade. He would have created an entirely new currency, the "bancor," which would be used only to settle international accounts and keep any deficits or surpluses from becoming too large.

This idea was not adopted, so the dollar has become the de facto international reserve currency in bancor's stead. It's not as good as bancor would have been, but it's far superior to the gold standard. The dollar is stable, backed by the world's biggest economy and most powerful military, and above all can be created in arbitrary quantities (as opposed to being dug up out of the ground). There is also no sign that the euro is replacing the dollar in this capacity — unsurprising, given the eurozone's endless economic chaos and idiotic design.

But dollars being the international medium of exchange — as Mason points out, 87 percent of foreign currency exchanges involve the dollar and some other currency, and dollars are 64 percent of foreign exchange reserves — means a huge demand for dollar-denominated assets. This has actually increased in recent decades, as financial deregulation led to large cross-border capital flows and thence to repeated balance of payments crises, prompting developing countries to build up huge reserve hoards to protect against predatory speculation.

All that demand for dollars means consistent upward pressure on the dollar's exchange rate — which makes American exports uncompetitive and imports cheaper. That, in turn, weakens the American economy as dollars are spent on goods and services from other countries — by quite a lot. The trade deficit was $37 billion in April, or 2.7 percent of GDP. That represents hundreds of thousands of potential jobs.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, any attempt to reduce the trade deficit is going to be met with countervailing policy by other nations that need dollar assets. They will implement austerity and tight money to slow their economy and reduce imports and restore the previous balance of trade. In short, if America tries to cut its trade deficit, the likely result is just a slowing of the world economy as a whole, and little if any improvement in the U.S. trade position.

So what should America do? Instead of trying to export our way to prosperity, we should embrace the responsibilities and opportunities of controlling the global reserve currency. Foreigners need dollar assets: Let's give them some.

Now, this should be done with care. One of the things that fueled the mortgage bubble was this desire for dollar assets. Wall Street produced tons of such securities back in the mid-2000s that looked very safe (through the magic of financial obscurantism and systemic fraud), but were in fact toxic waste.

However, the federal government can produce the absolute best dollar assets in existence, by simply borrowing money: U.S. Treasury bonds are as solid as they come. What's more, it can ensure that money is spent on productive public works (as opposed to thousands of McMansions in the Arizona desert).

But if that is too politically challenging, then the Federal Reserve could step in to help provide credit to various entities. Another option is establishing a national infrastructure bank, seeded with federal money but funded mostly by bond sales, which would provide funding for socially desirable projects — particularly environmentally-sound infrastructure and upgrades.

There is more to the story, and more options where we might direct that juicy free money. But the basic point is clear. The world runs on the dollar, which is both an opportunity and responsibility for the nation that controls it. But until a better system is built, America has to step up.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

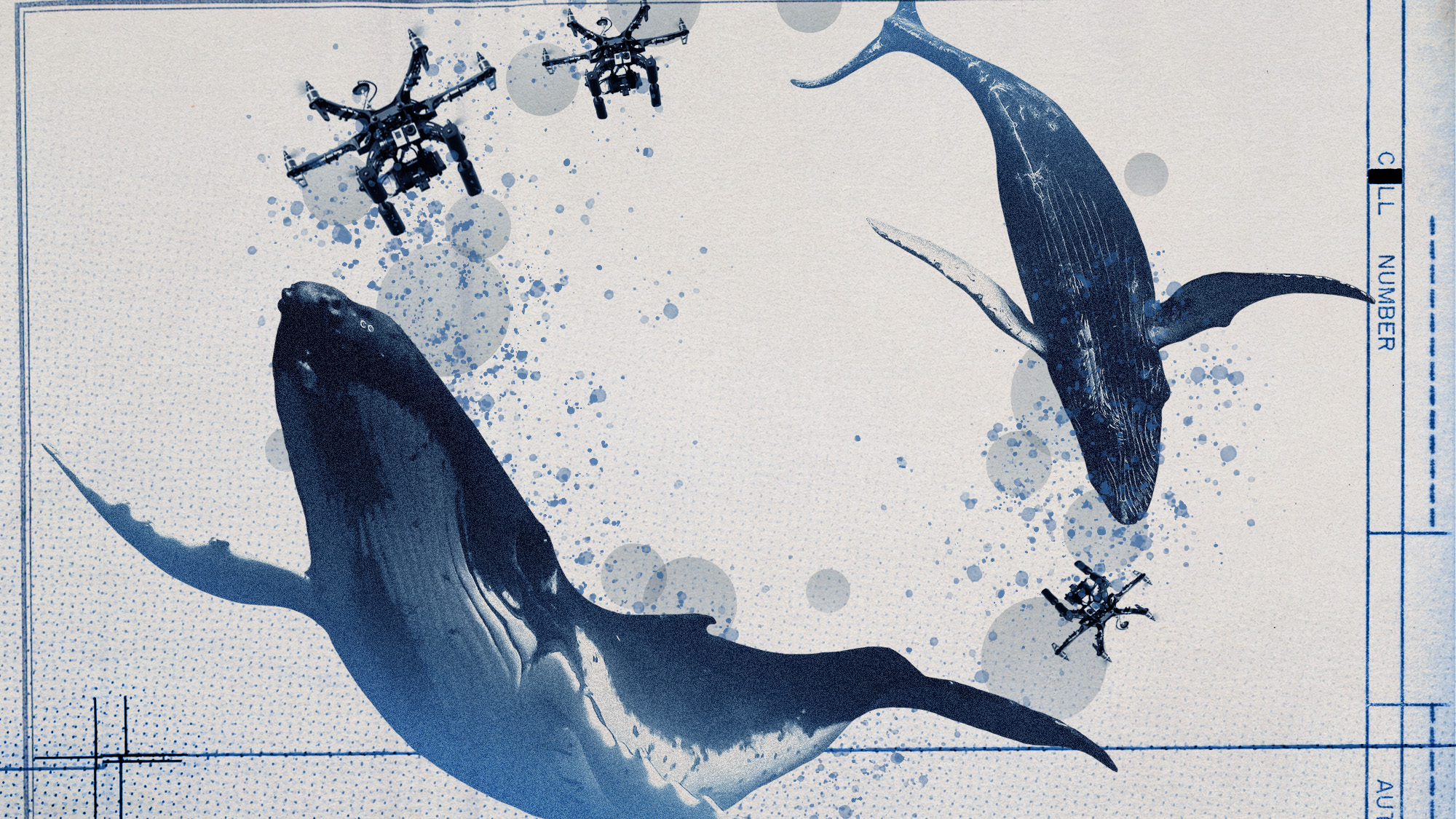

How drones have detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones have detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth Clearing the slate for his favorite elected officials

-

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of living

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of livingThe Explainer Telluride is the latest ski resort experiencing an instructor strike

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy