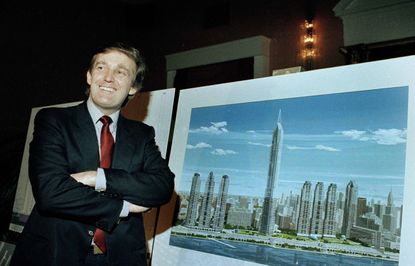

How Donald Trump built his business empire

Here's everything you need to know

Donald Trump often boasts about his "tremendous wealth." How did the Republican nominee amass his fortune? Here's everything you need to know:

How did he start out?

With a big leg up from his father. Fred Trump made an estimated $300 million building rental apartment villages in New York City's outer boroughs. Donald joined the family business after graduating from business school in 1968, but almost immediately set his sights on more glamorous real estate in Manhattan. In 1971, at the age of 25, he embarked on an ambitious project to replace a crumbling hotel near Grand Central Terminal with a Grand Hyatt. His father was instrumental in the deal: He lent Trump $1 million, guaranteed $70 million in bank loans, and used his political contacts to help his son get the project built. Completed in 1980, the development made Trump millions of dollars, and established him as a player in Manhattan real estate. "I had to prove — to the real estate community, to the press, to my father — that I could deliver the goods," he wrote in his 1987 best-seller The Art of the Deal.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What was his next project?

Trump used the profits from the Grand Hyatt deal to finance Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue, the 58-floor skyscraper where he still lives and bases his organization today. But his next venture almost bankrupted him. Eager to move into the lucrative world of gambling, he opened two casinos in Atlantic City, which was vying to become the Las Vegas of the East Coast. Launched in 1984 and 1985, Trump Plaza and Trump's Castle were initially successful. But the real estate magnate overstretched his empire with the Trump Taj Mahal, a glitzy, giant, $1 billion casino that siphoned off customers from the Plaza and the Castle. To service the huge loan Trump had taken out to build it, the Taj needed to take in $1.4 million a day — more than any other casino in history.

What happened?

The Taj lost vast amounts of money, and Trump's fledgling casino empire spiraled into irreversible decline. Between 1991 and 2009, its holding company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy four times. But Trump was saved by the power of his own celebrity status, which he had built up through his books, media interviews, and calculated leaks to the New York tabloids. Whenever creditors threatened to bankrupt Trump personally, he convinced them that doing so would destroy his brand and render what remained of the casino empire completely worthless. In the end, Trump's casino venture was an unmitigated failure — one that cost thousands of people their jobs and left dozens of small businesses without payment for their work in building or servicing the casinos. But Trump still extracted millions of dollars by awarding himself millions in salary and bonus payments. "I made a lot of money in Atlantic City," he said last year. "And I'm very proud of it."

What about his real estate?

Those ventures have been much more successful. His major building projects include Trump World Tower in midtown Manhattan, and Trump Tower in Chicago, the fourth-tallest building in the U.S. But after his failure in Atlantic City, banks became increasingly reluctant to lend him money. So Trump began focusing on monetizing his personal brand. Rather than building his own hotels and housing, Trump began licensing out his name to other developers. There are now Trump Towers and Trump Plazas everywhere — including Florida, Vancouver, Panama, and Istanbul — but Trump actually owns few of them.

What else has he put his name to?

As his biographer, Michael D'Antonio, put it: "Almost anything that might be sold as high quality, high cost, and high-class." Some of these ventures — such as the Donald J. Trump Signature Collection of shirts and ties, which are made abroad — have been moderately successful. But many more — among them Trump Steaks, Trump magazine, and Trump Vodka — sank without a trace. Other high-profile failures include the now-defunct Trump University, which is being sued by thousands of former students for fraud, and Trump Airlines, which lasted only three years. But Trump has enjoyed considerable success in one market: high-end golf courses. Since 1997, he has bought or developed 17 courses around the world, in locations including New Jersey, Scotland, and Ireland.

How much is Trump worth?

Bloomberg estimates his current fortune at $3 billion; Forbes puts it at $4.5 billion. Trump himself claims he is worth $10 billion, though he has admitted that this figure "goes up and down with markets and with attitudes and with feelings, even my own feelings." His repeated refusal to release his tax returns has prompted speculation that he is worth much less than he claims, and that he takes advantage of property tax law to report an income of zero — a trick he used to pay no income tax for several years in the 1970s and 1980s. His companies are also carrying at least $650 million in debt — some of it to the Bank of China. But Trump insists his net worth cannot be separated from the unique value of his personal brand. "It takes brains to make millions," Trump says. "It takes Trump to make billions."

Trump's mob connections

Over the decades, Trump has had many dealings with businesses and individuals linked to organized crime. For the construction of Trump Tower, he paid inflated prices for concrete from a firm partly owned by "Fat Tony" Salerno, the boss of the Genovese crime family, which controlled several labor unions. When he then hired 200 nonunion immigrant Polish workers — an act that would normally guarantee a picket line — work proceeded without any union action. There were more suspicious dealings in Atlantic City, where Trump leased land for his casinos from two men closely connected to the Scarfo crime family, and paid mobsters $1.1 million for a plot they had bought five years earlier for just $195,000 — a possible way of paying off the mob. But for many real estate developers in New York and Philadelphia at that time, mob connections weren't particularly uncommon. All developers "had to adapt," because of the mafia's control over building supplies and labor unions, says mafia expert James Jacobs. "That was the way it was."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The Nutcracker: English National Ballet's reboot restores 'festive sparkle'

The Nutcracker: English National Ballet's reboot restores 'festive sparkle'The Week Recommends Long-overdue revamp of Tchaikovsky's ballet is 'fun, cohesive and astoundingly pretty'

By Irenie Forshaw, The Week UK Published

-

Congress reaches spending deal to avert shutdown

Congress reaches spending deal to avert shutdownSpeed Read The bill would fund the government through March 14, 2025

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

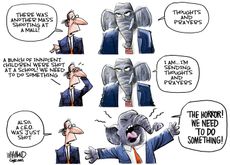

Today's political cartoons - December 18, 2024

Today's political cartoons - December 18, 2024Cartoons Wednesday's cartoons - thoughts and prayers, pound of flesh, and more

By The Week US Published

-

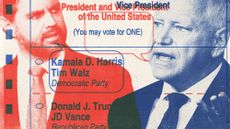

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?Today's Big Question Trump's hawkish pick for VP said UK is the first 'truly Islamist country' with a nuclear weapon

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attempt

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attemptSpeed Reads A 20-year-old gunman grazed Trump's ear and fatally shot a rally attendee on Saturday

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published