6 heartbreaking moments from Amy Schumer's new book

The book isn't all jokes. In fact, it contains a surprising amount of difficult material, thoughtfully rendered.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Amy Schumer's new essay collection, The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo, is often described as "hilarious." And it is. Even when the self-deprecating jokes about her appearance start to wear thin, Schumer compensates with the kinds of comedy curveballs that make her Comedy Central show a pleasure to watch. Whether she's compassionately describing a gorgeous hoarder's apartment or recovering after a matchmaker sets up her with someone who gets his jewelry from sharks, Schumer tackles the absurd with a deft hand.

But the book isn't all jokes. In fact, it contains a surprising amount of difficult material, thoughtfully rendered. The frankness Schumer is known for scans differently — and more powerfully — when she's recalling a sexual assault or recounting what it feels like to be in a codependent relationship with her mother. Her candor achieves some unexpected depths. Here are some of the more disturbing and moving instances. (And be warned — most of these are for an adult audience.)

1. On losing her virginity without her consent:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I looked down and realized he had put his penis in me. He was not fingering me. He was penetrating me. Without asking first, without kissing me, without so much as looking me in the eyes — or even confirming if I was awake. When I startled and looked down, he immediately removed himself from me and yelled quickly, "I thought you knew!" This seemed very strange to me, for him to protest so adamantly with such a prepared, defensive line — even though I hadn't yet said a word. I looked down and saw some blood on my bed. I was confused and hurt. He left soon after, and I rolled over and cried. [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

Schumer's restraint in this chapter is palpable: The dominant register throughout this whole account is confusion. She's telling this story the way many women experience it: as a combination of compassion and love for the offending party against a confused sea of unwanted contact and unexpected pain.

Our "templates" for sexual assault are few. One of the difficulties about the current conversation about rape is that everyone agrees in the abstract that sexual assault is a very bad thing, but when specifics come to light, our lens softens. Somehow the description of which part did what dissolves that horror into an agonized uncertainty that wants very badly not to think about it anymore. Shrug it off as a misunderstanding: Well, we say, a boundary got crossed in territory that's murky and hormonal and tough to police. This temptation is so strong that victims give into it too. For all this talk of a "culture of victimhood," the fact is this: Processing that someone you love caused you physical pain and violated you is actually extremely hard to do. It's almost always better to pretend you're okay and cry alone.

2. Trying to understand what happened:

Schumer talks elsewhere in the book about how her mother raised her to always "be okay" no matter what. What "being okay" means in this context is making things easier for others by refusing to recognize your own pain. It can make for intense confusion or (as Schumer does, when her mother leaves her father) getting inexplicable headaches. It means repressing or even denying that a bad thing happened in order to spare the people around you and (hopefully) convince yourself. Schumer's book illustrates this very well: "I was confused as to why he would have done this to me in this way," she writes, "but the most dominant feeling I felt was that the guy I was in love with was upset and I wanted to help him. I put my head on his chest and told him it was okay. I comforted him. Let me repeat: I comforted him."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I was still bleeding a little and feeling sore and terribly confused. What had happened was settling in, and I was getting sick to my stomach thinking about it. It made no sense. I was his girlfriend; we'd had conversations about sex and were very open when talking things through like that. ... If he'd asked me to have sex that night, I think I would have said yes. I didn't understand why he approached it the way he did. Did he feel like he needed to literally "sneak it in"? He had so much guilt attached to sexual activity, I recall, and lots of fear. Maybe he thought it would be a guiltless, shameless way to do it. Maybe, like the jerking-off sessions, it was easier for him to do it if I wasn't an active participant. I don't know. But he'd made the decision without me. It wasn't about us, it was about him. [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

3. On how she felt about sex for years after that:

Schumer's description of how her sexual attitude evolved out of this encounter is one of the more insightful things I've ever read concerning how early experiences program a person's intellectual as well as physical sense of their own sexuality. "The strangest part is that even though Jeff apologized and told me how bad it had made him feel, I don't remember ever really taking him to task about how it made me feel. I did what most girls do and continued on. ... I was 17 years old and I wanted my boyfriend to like me," she writes. They started having consensual sex a couple of months later. (Think of how that would play in a courtroom! But her reasons, as sketched out here, make a sad but perfect sense.) "The second time we did it," Schumer writes, "I tried to pretend it was the first time. I even went in my mom's room after and told her I'd lost my virginity."

But it was a lie, and I'd also be lying now if I said it didn't feel like my whole experience was ruined. My trust had been shattered — not just my trust in him but, in a lot of ways, my trust in anyone. My fantasy of a beautiful intimate memorable moment between two people had been taken from me in a flash. He took it. I didn't know it then, but I know now that it toughened me up in an irreversible way. For many years, when it came to sex, I didn't get the luxury of just being myself. Half of the time I was too defensive and guarded, assuming the guy wanted to hurt me or take too much. The rest of the time, I was too flippant — almost to the point of being dissociative, as if the act of sex didn't matter much to me. [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

4. On abusive relationships:

I think somewhere in the course of our relationship, I started to confuse his anger and aggression for passion and love. I actually started to think that real love was supposed to look like that. The more you yelled at each other, the more you loved each other. The more physical and demeaning it got, the more you were really getting through to each other. And the more I was willing to stand by him, the more he'd understand I truly loved him and that we should be together forever. And he always felt so bad about what he'd done after he shouted or bruised me. Surely he wouldn't beat himself up so much if he didn't love me so much. It's not abusive if they feel really bad afterward and promise to love you the rest of your life, right? Right? [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

5. On the shooting at a showing of Trainwreck:

I read about the disturbed man who killed Mayci and Jillian and injured nine other people. I don't believe in giving mass shooters their moment in the sun. I don't want to write his name. I never have and never will say it. But I do want to outline some facts about him. He loved the Tea Party. He publicly hated women and praised Hitler. This man purposefully selected my movie as a place to shoot and kill women. [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

6. On whether it's a comedian's place to philosophize about gun control:

I've mostly been able to find the humor in the absolute darkest moments. It's hard to do that with this, though. ... When I've written sketches about gun safety on my TV show, people have responded by saying they wish I'd just be funny. They tell me to stick to comedy because that's what they come to me for. I'll tell you what I tell them: No! I love making people laugh and am grateful that I'm equipped to do that. But when an injustice affects me deeply, I will speak about it — and I suggest you do the same. ... I think about Mayci and Jillian every day. I carry pictures of them on the road with me, and when I see that yet another American or several Americans were killed senselessly and avoidably by guns, all I can think is enough is e-f--king-nough. [The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo]

The real value of Schumer's essay collection is not its humor. It's the richer and weirder (and not always successful) discussion of control and autonomy. Schumer offers a messy object lesson in unlearning the frames we grow up with. If Schumer recognizes (and sometimes even capitulates to) society's invitation to repress things it prefers not to recognize, the book works as well as it does because we often see her really struggling with this. The essays that fall into the How I Did It category are much less interesting than her How I'm Trying To Do It pieces.

That seems right. Schumer advocates making giant mistakes (the book's title even references one), and she's made plenty. That's to be expected as we grope toward a world capable of producing, rather than demanding, "okayness."

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peace

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peaceUnder the Radar Crowds have turned out on the roads from California to Washington and ‘millions are finding hope in their journey’

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’The Week Recommends Put an end to endless swiping and make real romantic connections

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

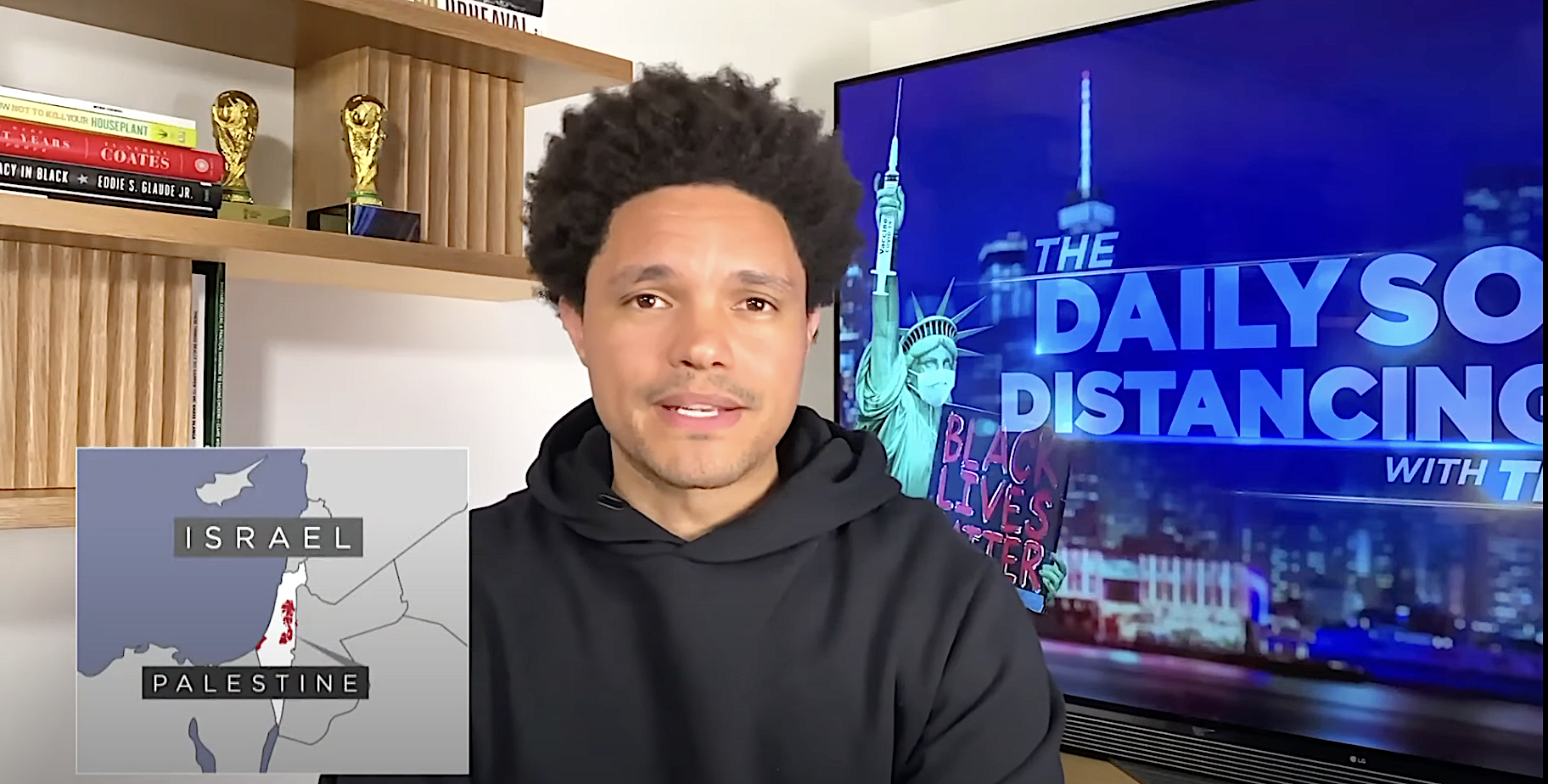

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read