Who will inherit America?

Why liberals need to talk about posterity

The debate about immigration in the United States has touched on nearly every clause mentioned in the preamble to the Constitution.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

What makes for a more perfect union — a greater moral perfection, or a more unified polity? What establishes justice — punishing rule-breakers who jump the line, or remedying injustices perpetrated by others?

Is domestic tranquility threatened by too-readily letting in people who may wish us harm — or does the common defense require making common cause with those who share with us a common enemy?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How can we best promote the general welfare — by protecting vulnerable workers and struggling homeowners from competition? Or by welcoming those with the drive and determination to cross an ocean or a desert to build a new life?

We know how to debate these kinds of questions, and few dispute the legitimacy of that kind of debate. But there's another word that we have a harder time debating: Posterity.

While Thomas Jefferson mused about the need for a revolution every 20 years, the framers of the Constitution thought they were establishing something of greater longevity, something that would endure beyond the lifetimes of those who wrote it, howsoever much it might require periodic amendment. It was intended to secure blessings not only for themselves, but for their posterity.

At its most fundamental level, the debate about immigration is a debate about whether we, the people, get to decide who those future generations will be.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In our private lives, few would accept leaving this question — who inherits our property, our name, and the custody of our reputations — to forces entirely beyond our control. Most of us think seriously about who we marry, who we will have children with. Even those of us — like myself — who are adoptive parents recognize that the choice to adopt is exactly that: a choice.

Questions of identity — of who we are — are just as fundamental to any political community. A shared sense of identity is what makes collective action possible, whether that action is financing a community center or fighting a war. Any time we make sacrifices today to benefit generations yet unborn, we imply an identifying bond between the present and the future. And yet, for many supporters of immigration there is a real dispute about whether this is even a valid political question — or, on the contrary, whether freedom of movement is an inalienable right, or whether asking questions about national identity is inherently racist.

In a piece that considers deeply how immigration advocates have gone wrong, Josh Barro argues for the need to make the case for a relatively liberal immigration regime as being in the national interest (as opposed to just being "the right thing to do”). And he’s right about that. But before that case can be made, they need to win the trust of those who suspect — perhaps rightly — that immigration advocates see "the national interest" as the interest of a corporate entity known as the United States of America, without regard to what the nature of that entity is, or who it exists for in the first place.

If they can't rule questions of identity out of bounds, liberals will be tempted to answer them with ideological definitions of Americanism that implicitly deem large numbers of actual Americans to be less-than-faithful communicants of the national religion (something conservatives have been prone to do at least as much). It's an approach that is distinctly unlikely to win over anyone not already singing from their hymnal.

So how can those with a more expansive conception of American identity make their case? The answer begins with a return to that word: posterity.

From the perspective of the founders, we are their posterity, whether our ancestors are from England, Ethiopia, or Ecuador. They are our ancestors. And what they have bequeathed to us — from our political institutions down to the land itself — is our inheritance.

We all have varied relationships with our individual parents. Some of us live in awe of their shadows; others of us cringe at their failures; still others of us have spent years working our way through the residue of abusive childhoods. And some of us are lucky to stand tall and proud on our forebears' shoulders. For all of us, they are still the people to whom we owe our beginnings. We can love them, hate them, live in illusion, or see them for who they are — but we cannot disclaim them.

The same is true of our political ancestors — and we need to talk that way.

If we want to share our inheritance more broadly, and convince our cousins to do the same, we need first to be able to demonstrate that we cherish it, that we recognize that it is our inheritance, something we, as individuals, did not create, but was given to us by those who came before, and that we are responsible for passing on. If it is ours, then we have the right to remodel it to suit better suit the needs of the present and the future — we don’t have to be shackled by the past. But if we care about it as an inheritance, then we’ll show gratitude for what we have received, and make changes in that spirit, even if we know that many of those who came before would have cringed to see just who has taken up residence in what was once their house, and what they’ve done to the place.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

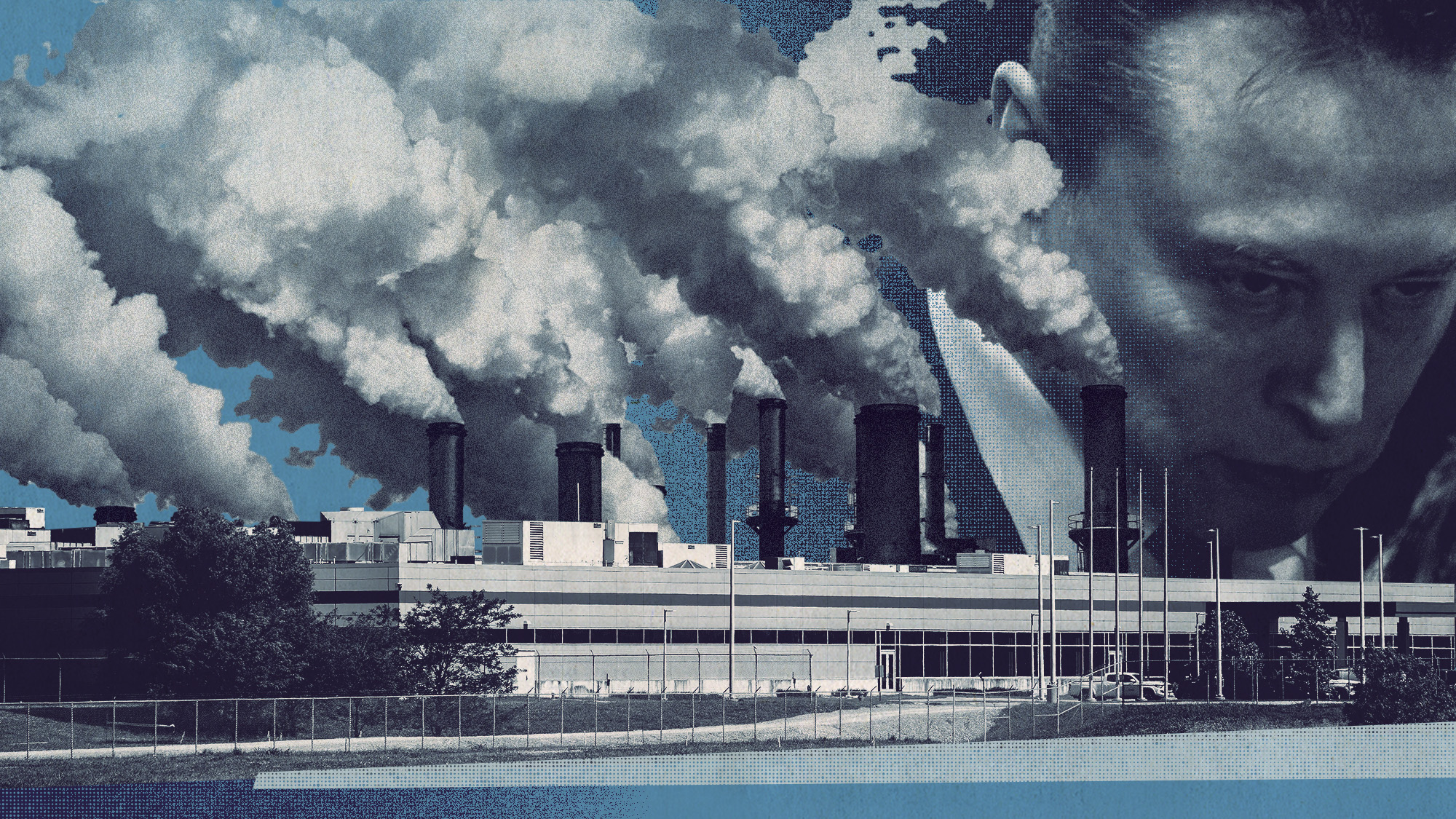

Inside a Black community’s fight against Elon Musk’s supercomputer

Inside a Black community’s fight against Elon Musk’s supercomputerUnder the radar Pollution from Colossal looms over a small Southern town, potentially exacerbating health concerns

-

Codeword: December 4, 2025

Codeword: December 4, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week

-

Sudoku hard: December 4, 2025

Sudoku hard: December 4, 2025The daily hard sudoku puzzle from The Week

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration