Presidential pardons, explained

Presidents have almost unlimited power to grant clemency for federal crimes — but they don't always use it wisely

Presidents have almost unlimited power to grant clemency for federal crimes — but they don't always use it wisely. Here's everything you need to know:

Why was this power created?

The Constitution's Article II, Section 2 gives presidents the power to grant pardons "for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment." Pardons can free people convicted of crimes from jail terms, formally forgive them without expunging their criminal records, and restore certain rights — to vote, or bear arms, for example. The Founders saw presidential pardons as a last resort for people wronged by the courts. Otherwise, "justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel," Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist Papers. Still, the "principal argument" for the power, he said, was to restore "tranquility" in case of armed resurrection — which motivated George Washington in granting the first pardon (see below) and Abraham Lincoln's decision to pardon Confederate soldiers and all but the highest Confederate officials. When President Trump tweeted he had "complete power to pardon," he wasn't far off — chief executives have almost unlimited latitude to put aside convictions (but only of federal crimes), and they haven't been shy about using it. "For most of American history," says political scientist P.S. Ruckman Jr., "presidents pardoned frequently, early, and often."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does the pardon process work?

Typically, offenders make a formal request to the Justice Department's Office of the Pardon Attorney, which advises on executive clemency. (The DOJ imposes a five-year waiting period after the pardon seeker's conviction or release.) The pardon office evaluates the request, then makes a recommendation. There are times, however, when presidents circumvent this process. Former Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio, a staunch Trump supporter, never submitted a pardon request; indeed, he'd yet to be sentenced for a contempt conviction arising from allegedly brutal and discriminatory immigration-enforcement practices. Yet the president pre-emptively pardoned him. While pardons often do remedy injustice, "presidents have repeatedly used this power for their personal, political, and familial interests," says constitutional scholar Jonathan Turley.

When has the pardon been abused?

Abuse can be in the eye — and politics — of the beholder. Thomas Jefferson was widely criticized for pardoning allies convicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts. More than a century later, President Warren G. Harding was accused of selling pardons for contributions, and gave one to a mob enforcer suspected in 60 murders. Franklin D. Roosevelt pardoned Conrad Mann — convicted of running an illegal lottery — mainly because he was a close associate of Kansas City's notorious Democratic boss Tom Pendergast. In 1971, Richard M. Nixon granted clemency to Teamsters President Jimmy Hoffa, who was doing 15 years for jury tampering and fraud; in 1972, the powerful Hoffa threw the union's support to Nixon's re-election bid. Of course, it was the 37th president himself who benefited from the most hotly debated pardon in U.S. history.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened?

When Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal in 1974, he still faced potential prosecution for obstruction of justice and other charges. But a month after taking office, President Gerald Ford addressed the nation and offered his predecessor "a full, free, and absolute pardon" for crimes he "committed or may have committed." Ford said he'd hoped to spare an already traumatized nation a divisive prosecution of a former president, but many suspected that Nixon had made a deal with his vice president to resign in return for the pardon. Ford's pardon contributed to his 1976 election loss to Jimmy Carter. "The pardon exacerbated the public's distrust of government," says historian Rick Perlstein, "reinforcing Americans' sense that the president was above the law." It was hardly the last pardon to invite that perception.

What other pardons were controversial?

George H.W. Bush caught heat for pardoning Reagan Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, indicted for perjury in the Iran-Contra scandal, along with five other defendants. Bush was Reagan's vice president during the illegal sale of arms to Iran, admitted having been present during discussions of the scheme, and was likely to have testified during the trials. President Bill Clinton very liberally used his pardon authority to benefit allies, including his own half-brother, Roger Clinton, and fugitive financier Marc Rich. Rich was "one of the least worthy recipients of a pardon in modern history" — a fugitive from justice who was "unrepentant for his tax evasion, racketeering, fraud," and illegal oil deals with Iran. President Barack Obama granted just 212 pardons, one of the lowest rates of any president. He did, however, commute sentences for 1,715 inmates, primarily nonviolent drug offenders serving harsh "mandatory minimums," as well as for ex–intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning, who'd served seven of 35 years for passing secrets to WikiLeaks.

How might Trump use the pardon?

There is speculation he may blunt special counsel Robert Mueller's Russia investigation by pre-emptively pardoning everyone in his inner circle. Constitutional scholars disagree about whether Trump has the power to pardon himself. But Jeffrey Crouch, author of The Presidential Pardon Power, says a Trump self-pardon could very well backfire. A 1915 Supreme Court decision deemed accepting a pardon an admission of guilt. "The standard for impeachment — 'treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors' — is not criminal, it's political," Crouch says. "So an acknowledgment of guilt made via a self-pardon could actually become a starting point for impeachment."

The first pardon

Presidential pardons began with whiskey — more precisely, a hefty tax on spirits enacted in 1791 to pay down Revolutionary War debt. The levy (as much as 30 percent) was a burden to poor farmer-distillers and sparked violent protests. While President Washington counseled "forbearance," Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton urged a more vigorous response. The so-called Whiskey Rebellion climaxed on July 17, 1794, when 500 insurgents burned the home of tax supervisor John Neville outside Pittsburgh. Reluctantly, Washington himself led a militia force of 13,000 to the area and easily put down the revolt. Two rebels — John Mitchell and Philip Weigel — were convicted of treason and sentenced to death. But on July 10, 1795, Washington granted them the first presidential pardon, expressing his belief that the new American government ought to exercise "every degree of moderation and tenderness which the national justice, dignity, and safety may permit."

-

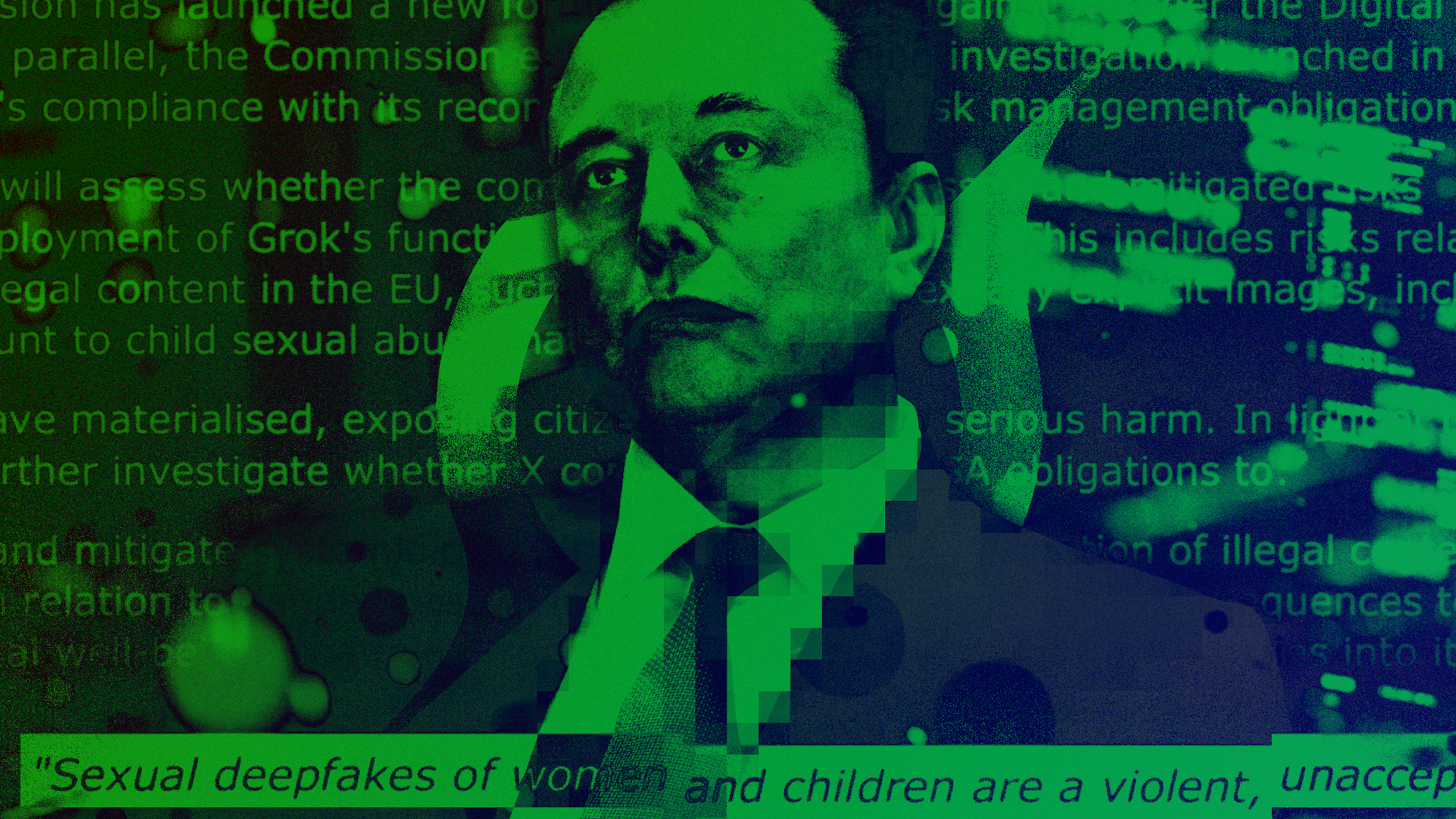

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred