The CNN town hall on gun control was a failure. And that's good for our democracy.

Why America needs to see more political debates where no one "wins"

Americans are addicted to cheap political sentiment. "Own the libs" has become a kind of motto for much of the right, some members of whom recently resorted to mocking survivors of the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The left, overwhelmed by the tidal wave of contemptible sludge emanating from this White House, tilts at it with angry, constant, and useless charges of hypocrisy. Conversation isn't exactly easy in this climate. We communicate in memes. The problem is partly that we appear to have lost any format that allows for sincere, substantive disagreement. Networks have long since calcified TV "debates" into spectacles so rote they're almost dance-like in their predictability. We'd rather preach to the choir than really engage.

That seems to finally be changing. Take the #NeverAgain movement started by survivors of the Florida school shooting that killed 17. These teens mobilized with passion, speed, anger, and savvy against the gridlock we mistake for pragmatism in this political climate. Their achievements have shocked a country that no longer really believes in political solutions. Wednesday night's CNN town hall was historic, and not because the confrontation between a grieving community and its representatives is unprecedented (it's not, and it shouldn't have been as impressive as it was to see lawmakers facing their angry constituents). It's historic because no one came out of that town hall the clear victor, and we as a society aren't used to political disagreements that don't end with an obvious "win." But uncomfortable confrontations like these, in which there is no conversion or resolution or repentance on either side, are real and instructive. We need to see many more of them.

There's perhaps no better illustration of the staged political theater we've grown accustomed to than the "listening session" the president held with educators and students compared to the town hall later that same day. The former was a pathetically sanitized affair. The students leading the charge for gun control, like Emma Gonzalez, were not invited. Those present dutifully praised and thanked the president (whose leaden inadequacy is perfectly captured by the revelation that he needed a note reminding him to say "I hear you" in a listening session). And they did so in an environment he completely controlled.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The president's remarks (which included typical Trumpian word salads like "we're going to be very strong on background checks" with "very strong emphasis on mental health on somebody") were typically infelicitous. In this he was joined by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who opened the proceedings by hoping that "by talking and by listening, we can make something that was unthinkably bad something good." There being no circumstance in which a grieving parent could find such a conversation, however transformative, "good," DeVos' phrasing was as awkward as the event itself. The footage shows traumatized and bereaved citizens eloquently channeling their inexpressible emotion into a ritual so empty that Hunter Pollack, a brother of one of the victims, accidentally gave the game away: "We had a very effective meeting before we walked in this room," he said, adding that he trusted the president and needn't say anything more. It couldn't be clearer, to anyone present or anyone watching, that this was not the meeting that mattered. This was not going to be a place where solutions were seriously discussed.

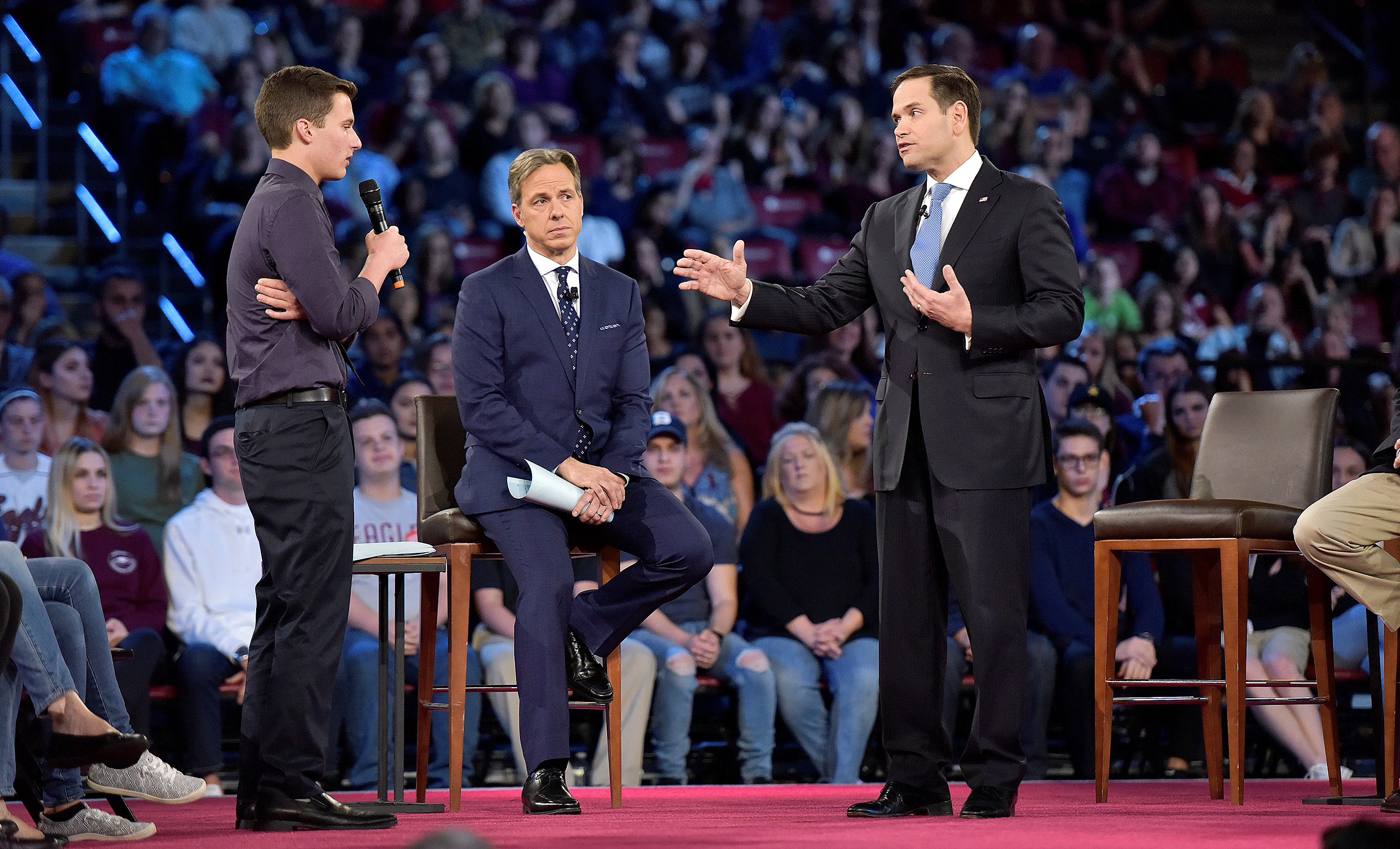

The 2.5-hour town hall, mediated by CNN's Jake Tapper, was a stunning contrast. For one thing, it gave grieving students, parents, and teachers in Florida a forum to confront lawmakers and corporate interests as equals. The result was electrifying and substantive: Murdered teen Jaime Guttenberg's father asked Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) to admit that guns were a problem. Ashley Kurth, a culinary arts teacher at Stoneman Douglas who sheltered 65 students during the shooting and identified herself as a Trump voter, asked whether the president's suggestion that teachers be armed meant she now had to train and wear a Kevlar vest in addition to educating her students. (Rubio said he did not support the proposal.)

Perhaps the most dramatic moment came when high schooler Cameron Kasky asked Rubio whether he would, in the future, reject donations from the National Rifle Association. "That's the wrong way to look at it," Rubio hedged, "people buy into my agenda." In the ensuing exchange, Kasky persisted: "In the name of 17 people, you cannot ask the NRA to keep their money out of your campaign?" Rubio, who said he supported raising the age at which you can buy a gun from 18 to 21, refused to reject NRA funds: "I will always accept the help of anyone who agrees with my agenda," he concluded, lamely. The teen drove the ugly contradiction at the heart of Rubio's answer home: "Your agenda is protecting us, right?" he said.

Judging by reactions online, viewers were stunned by this exchange. People were certainly impressed by Kasky's poise and persistence (especially given his youth). But we're also just totally unused to platforms where follow-up questions like these are asked, let alone answered. It felt, in a very small way, revolutionary. That's partly due to the kids' lack of deference. It is genuinely unusual to see citizens treat their public servants as public servants, but Kasky and the other students behaved as though the idea of public service was more than a polite fiction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The format even seemed to give the politicians a way to talk to each other. Rep. Ted Deutch (D-Fla.) and Rubio appeared to have a genuine (if heated) exchange of ideas over how to move forward with shared legislation. It may have been theater, but it felt like we were witnessing a conversation between them that they would not otherwise have had.

That doesn't mean anything was solved. There are hard limits to what this kind of spectacle can do. Any hope of converting Rubio (or NRA spokesperson Dana Loesch, who sternly condescended to the bereaved crowd in a tornado of deflection) was slim. Within a couple of hours of that town hall, Rubio was already walking back any hope of progress.

But spectacles like these aren't actually about producing his moment of conversion. They're about producing ours.

This was a confrontation in which no one changed their mind. It breaks with a long CNN tradition of fake disagreements we've learned to detect. In a world filled with videos of fake debates and fake conversions, the town hall did the unthinkable: It failed. Sincerely. There are other recent TV events I've found similarly powerful. One is an uncomfortable Jimmy Kimmel segment, in which Kimmel mediates a meeting between a DACA recipient studying to be a nurse and a group of people who believe she ought to be deported:

This segment broke with its genre and became uncomfortable and irresolute and — in a word — true. It's kind of amazing that this even made it on the air. Then again, that's precisely its power: It smashes our expectation of a feel-good late-night segment and leaves us hanging, yearning for a resolution that won't come. Something similar happened back in December of last year when John Oliver confronted Dustin Hoffman at a Tribeca film panel over allegations that he'd sexually harassed a teenager on a set. Oliver's willingness to defy the staid constraints of the panel honoring the old actor — and Hoffman's refusal to admit wrongdoing — made for an unsettling encounter that did not resolve. It was unpleasant to watch. It lacked polish and the dance-like consensus that informs these sorts of clashes. And, as a result, it felt disruptive and oddly important.

What all these spectacles share is a certain immunity to the "spin" we've come to expect out of every onscreen engagement. Oliver wasn't having it when Hoffman attempted it; neither was Kimmel. But the CNN town hall was the biggest, splashiest instance of disruptive engagement we've seen in awhile because a crowd of 7,000 people was holding elected officials accountable. It was a massive, illuminating confrontation that engaged substantively, and substantively failed. But it was real, and thanks to that event, the limits of what feels possible have expanded.

Spectacles of failure like this are instructive, and what conversions they produce are outside the frame. One of the students at that CNN town hall asked Deutch if our democracy was broken. "A little," he replied. He's right. And a society that's failing needs to see failure modeled. For years now, scientists have been calling for scientific journals to publish more "null results," that is, studies with inconclusive findings. Null results have value. They quietly build up the base on which progress depends.

We need null results in our entertainment and politics, too. In a discourse awash with memes and sneering displays of certainty, we need to see more videos like this town hall. Failure instructs. It's useful to see that our failures to persuade on Facebook or in person or wherever are symptomatic rather than exceptional. But those efforts to persuade are useful even (or especially) when they fail. Because they show the rest of us what unreasonable, even monstrous intransigence looks like. And they teach us to keep fighting anyway.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

5 editorial cartoons about ICE killing Renee Nicole Good

5 editorial cartoons about ICE killing Renee Nicole GoodCartoons Artists take on ICE training, the Good, bad, ugly, and more

-

Political cartoons for January 10

Political cartoons for January 10Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include a warning shot, a shakedown, and more

-

Courgette and leek ijeh (Arabic frittata) recipe

Courgette and leek ijeh (Arabic frittata) recipeThe Week Recommends Soft leeks, tender courgette, and fragrant spices make a crisp frittata

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred