How the NHS is failing children on mental health

Major new study finds level of provision for young people in UK ‘lags far behind’ other EU countries

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Child mental health services in the UK are significantly worse than those available in many other European countries, according to a major new report.

The Milestone Project, a wide-ranging study of the EU member states, concluded that access to mental health inpatient services for children and teenagers “varies significantly” from nation to nation, with some countries “providing up to 50 times more beds” per capita than others.

Britain has 9.4 specialist hospital places per 100,000 under-18s for those suffering from conditions such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, self-harm and suicidal thoughts. That puts the UK 18th out of the 28 EU nations, “despite having the largest number of services dedicated to child and adolescent mental health” in the study area, The Guardian says.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The newly published data indicates that UK is “lagging far behind” even countries in Eastern Europe such as Latvia, Estonia and Slovakia, which have far lower GDPs, when it comes to the specialist provisions.

Sweden had the fewest inpatient beds, with 1.2 beds per 100,000 young people, while Germany had the most, at 64 beds.

According to HuffPost, “around one in ten children aged five to 16 are thought to be affected by a mental health issue” in the UK, and 50% of lifelong mental health conditions manifest by the age of 14.

But the UK’s low ranking in the new study indicates that under-18s are not getting the care they needed, experts warn.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Swaran Singh, a professor of psychiatry at Warwick University, said the youth of the UK “deserve better than what they currently receive”, and that “the UK sadly lags behind other EU countries on many indicators, especially on the number of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) psychiatrists”.

Singh is one of many analysts who believe a lack of funding is the primary reason for the significant downturn in mental health treatment.

“The Milestone Project has shown how far we are from providing much-needed help and care to vulnerable young people at the time of their greatest need,” he added. “Despite repeated promises by successive governments of increased funding into youth mental health care, the state of the services remains parlous.”

Theresa May has insisted in the past that “tackling the injustice of mental illness” is one of her “absolute priorities” as prime minister. Her government has promised to treat mental health as seriously as physical health, and claims it is spending a record amount on mental health services.

Analysis by health think-tank The King’s Fund indicated that 84% of mental health trusts, which provide the majority of mental health services, received a funding increase in 2017.

But the increase masks an ongoing imbalance in health spending. Mental ill health accounts for 28% of the overall disease burden but receives just 13% of NHS funding.

Mental health provision for young people in the UK also varies wildly by location, according to Tom Madders, director of campaigns at the charity YoungMinds.

“If young people are so unwell that they need inpatient care, it’s vital that they can get it quickly and as close to home as possible,” he said. “But at the moment, families in the UK are too often forced to travel long distances to inappropriate out-of-area placements because services are overstretched.”

Figures obtained by the British Medical Association in 2017 showed that seven in ten children and teenagers with severe mental health problems were being treated in hospitals outside their region, with some sent hundreds of miles away.

“It can be an incredible wrench for children to leave their homes and being based far away is not going to help a young person in crisis,” BMA community care chair Dr Gary Wannan told The Daily Telegraph.

Another issue is that GP appointments are often too short for doctors to help young patients suffering from mental health problems. According to Healthwatch Lambeth, part of a nationwide network of health watchdogs, patients and GPs alike have suggested that “double appointments should be booked when individuals indicate there are mental health needs involved”.

HuffPost adds that in the UK - as in the majority of European countries - when service users reach a certain age, usually 18, they are “no longer eligible to use children’s mental health services and are instead moved to adult services”, which “can mean uncertainty and the loss of the support that has helped them so far”.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youth

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youthIn The Spotlight Obsession with beating biological clock identified as damaging new addiction

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?The Explainer Surge in cases of new variant H3N2 flu in UK and around the world

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

The ‘menopause gold rush’

The ‘menopause gold rush’Under the Radar Women vulnerable to misinformation and marketing of ‘unregulated’ products

-

The app tackling porn addiction

The app tackling porn addictionUnder the Radar Blending behavioural science with cutting-edge technology, Quittr is part of a growing abstinence movement among men focused on self-improvement

-

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypes

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypesUnder the radar They could lead to more accurate diagnosis and care

-

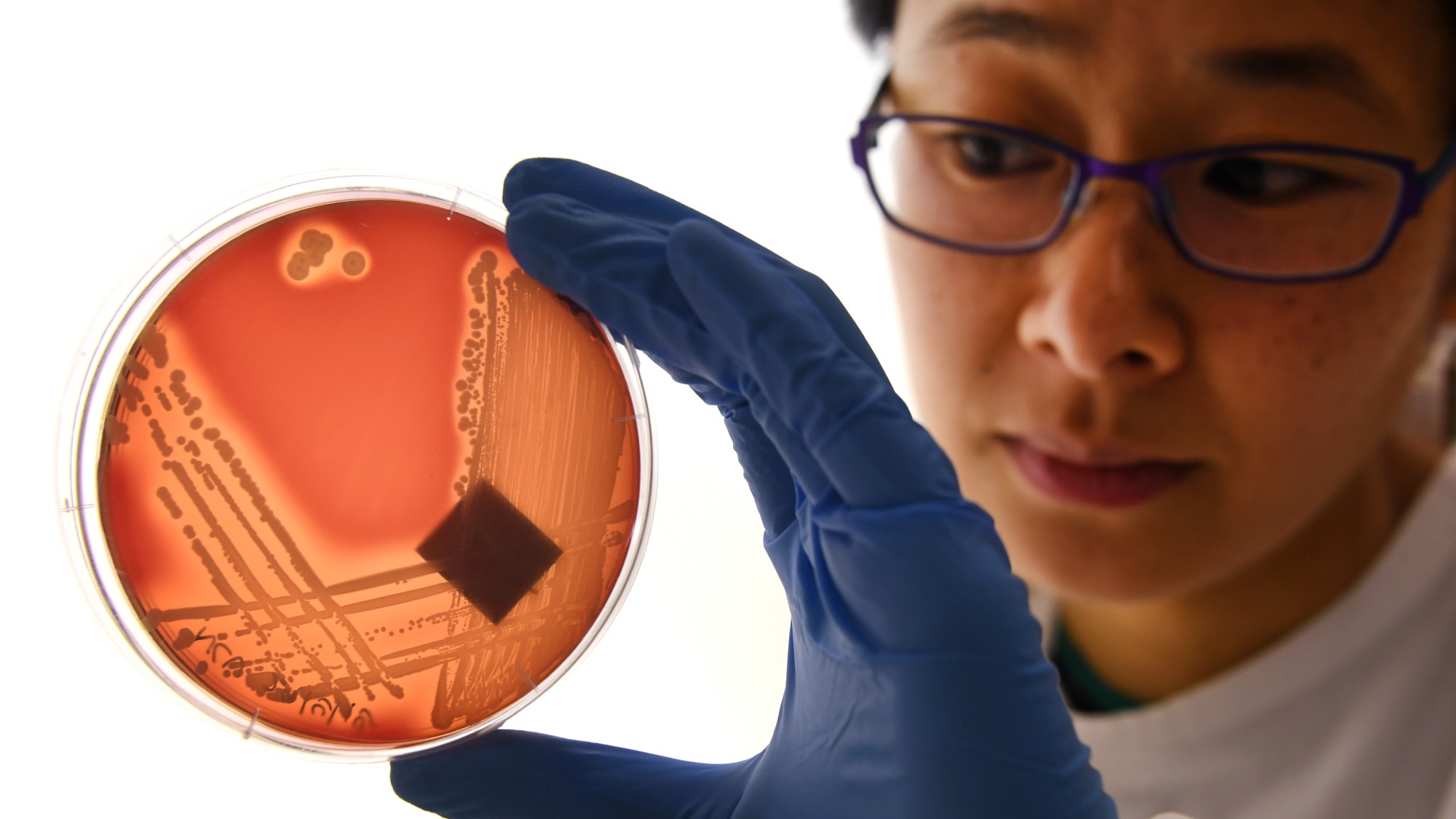

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugs

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugsThe Explainer Antimicrobial resistance is causing millions of deaths. Could a faeces-filled pill change all that?