How Brexit shaped the UK’s coronavirus response

Boris Johnson will not ask for more negotiating time despite pandemic disruption

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Boris Johnson’s government has insisted that the UK will not prolong the Brexit transition period beyond 31 December, despite the disruption to negotiations caused by coronavirus.

The UK formally left the European Union on 31 January, and at that point the government had not realised the threat that the coronavirus posed to public health, the economy and society.

In mid-April, with the UK at the height of the coronavirus crisis, Britain’s top Brexit negotiator, David Frost, said bluntly: “Transition ends on 31 December this year. We will not ask to extend it. If the EU asks we will say no,” Politico reported.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Did Brexit impact the coronavirus response?

When Johnson took the UK out of the EU at the end of January, he said it was an opportunity to “unleash the full potential of this brilliant country and to make better the lives of everyone in every corner of our United Kingdom”, The Sun said.

The day before, the emergency committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) had formally declared coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Earlier this month, Johnson’s government was criticised for failing to explain why the UK did not take part in an EU scheme to source medical supplies urgently needed to tackle the coronavirus outbreak.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ministers were forced to deny that a “political decision” was taken to opt out of the programme to procure personal protective equipment (PPE) for front-line healthcare workers, despite that being their original line.

A government spokesperson said in March that the UK was not taking part in the scheme because it was “not in the EU”.

But after a backlash, they changed that line, claiming that the EU email inviting the UK to join the scheme had been sent to an out-of-date and defunct email address.

Then, last week, the Foreign Office’s most senior civil servant, Simon McDonald, said that the UK’s opt-out of the EU scheme had been a deliberate choice. “It was a political decision. The UK mission in Brussels briefed ministers about what was available, what was on offer, and the decision is known,” The Guardian reports.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock subsequently denied those claims, and McDonald was forced to retract his comments.

As Politico notes, the crisis has made “abundantly clear [that] London does not want to lean on the EU to help coordinate its response”.

The site reports that “Matt Hancock is not attending – and has not been invited to – meetings of EU health ministers”, adding that “Brexit means Brexit, even when it comes to coronavirus”.

“While still paying into the EU budget and able to access EU infectious disease databases until the end of the transition period, the UK is officially out of the club… and no exception has been made for the growing international health crisis, the first such event to test the post-Brexit relationship.”

The government responded in unequivocal terms earlier this month to an online petition requesting a Brexit transition extension: “The transition period ends on 31 December 2020, as enshrined in UK law. The Prime Minister has made clear he has no intention of changing this. We remain fully committed to negotiations with the EU.”

Should negotiations be suspended?

As The Guardian reports, “viewed from today’s unimaginably changed perspective, this year’s pre-crisis months can seem like a parallel world”.

Prior to the arrival of the coronavirus, “Johnson’s media backers were feting him then for winning the ‘Get Brexit Done’ election”.

However, with the coronavirus delaying talks, the Conservatives’ election slogan has become even more contentious.

Negotiations between the UK and EU about a long-term trade deal are ongoing, though they have been disrupted and moved online owing to the spread of coronavirus.

The EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, said progress in four areas of discussion had been “disappointing”, while the UK government released a statement saying there had been only “limited progress was made in bridging the gaps between us and the EU,” says the BBC.

What is agreed with the EU will dictate the UK’s new customs and immigration arrangements, and businesses, officials and the public will need time to prepare for those changes.

The UK is using this need for clarity as a reason to push ahead with talks, claiming that businesses need to know about the new trading arrangements.

And some economists believe that the British government may hope to use the economic damage of coronavirus to strengthen its hand, given the City of London’s status as a finance centre.

“The City of London is going to be very important as a way for governments to raise money,” Tony Travers, a professor of politics at the London School of Economics, told The New York Times. “They may think the EU will be more concerned about upsetting things, given the scale of coronavirus, and may give them a better deal.”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Will the transition period be extended?

“Many assumed the two sides would quietly agree in June to extend the talks,” says the New York Times. “Yet, if anything, Britain seems to be hardening its position, raising fears that a second economic shock – over Brexit – could hit struggling European economies.”

The government has not yet offered any reason for refusing to consider a Brexit transition period extension, other than the fact that 31 December has already been agreed as an end date. And critics say that the Brexit-backing leadership are making decisions politically, rather than practically.

“There are significant practical implications of not delaying; the question is whether the government cares about that, and at the moment they are showing every sign of not caring,” said Anand Menon, professor of European politics and foreign affairs at King’s College London.

“If it were the practicalities and the economics, rather than the politics, you would say there is nothing to lose by delaying,” he told the NYT. “If ever there was a force majeure argument for a delay, coronavirus is it. But I don’t think the practicalities are dominating yet.”

David Henig, director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy, thinks that Britain will not ask for an extension, but will attempt to strike the foundations of a deal.

“I think they are underestimating the challenge, but they think a deal can be done,” said Henig. “One or two others in government think that’s overly optimistic but also think that’s fine, too, without a deal.”

It might well suit the Brexiteer government to merge the economic shock from coronavirus and Brexit, which almost every bit of research – including the government’s own – shows will hit the country hard.

“The thinking seems to be that the economic costs of abruptly withdrawing from the European Union without a trade deal might be buried by the British government beneath the damage wreaked by the coronavirus,” says the NYT.

Three recent opinion polls show that twice as many British voters are in favour of extending the deadline as oppose it, the paper adds.

“At the moment they think that they can carry on being ideological on Brexit and can continue to carry the country with them,” said Henig.

“There are a series of risks if the government does not go for a deal or an extension,” he said. “Some of them will turn bad.”

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

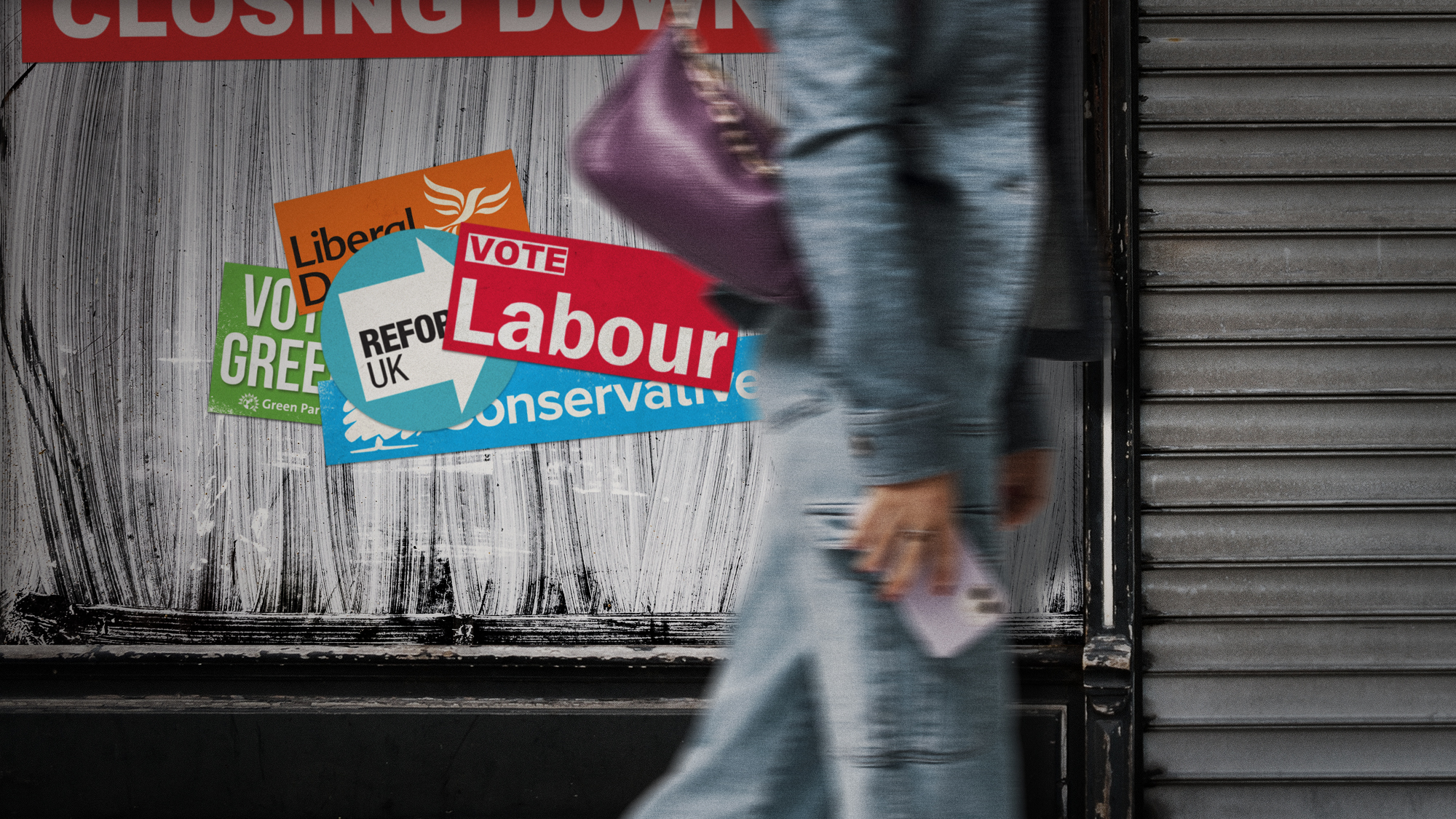

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Is Britain turning into ‘Trump’s America’?

Is Britain turning into ‘Trump’s America’?Today’s Big Question Direction of UK politics reflects influence and funding from across the pond