How the polio vaccine could curb coronavirus

Scientists hope the decades-old vaccination may provide protection against a second wave of Covid-19

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

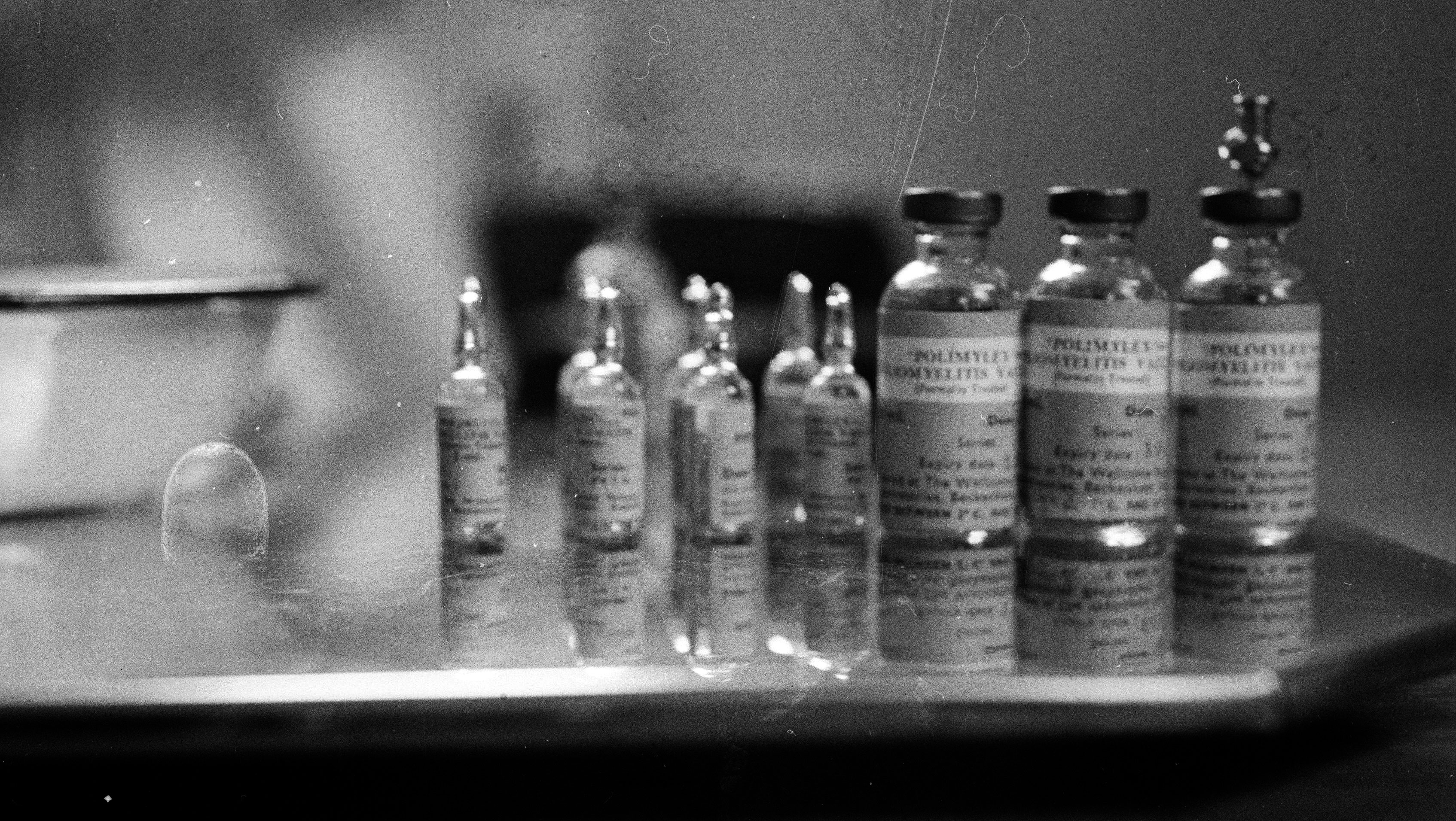

A vaccine developed in 1952 and delivered to generations of children on lumps of sugar could become the first line of defence against Covid-19, new research suggests.

Scientists from the Global Virus Network (GVN) say the vaccination against poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, “could provide temporary protection” from the new coronavirus.

The childhood immunisation is the second of its kind to be identified as a possible weapon against the ongoing pandemic, with large-scale trials already under way to test whether the BCG vaccine for tuberculosis could be used to tackle the health crisis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“If shown effective, those vaccines could potentially provide protection against the second wave of coronavirus, which is likely to crest before a covid-specific vaccine is widely available,” says The Washington Post.

The polio hypothesis

Like the BCG jab, the polio vaccine consists of a weakened - but still live - strain of the disease.

This “is expected to trigger a general immune response to any foreign organism”, during which the recipient develops antibodies to fight the specific virus or bacteria introduced into their body, says Forbes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And such vaccines may have a useful secondary effect.

“An increasing body of evidence suggests that live attenuated vaccines can also induce broader protection against unrelated pathogens,” write researchers from the GVN, a coalition of medical virologists, in a paper published in the journal Science.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

“A retrospective study from Denmark found that the use of OPV [oral polio vaccine] was associated with reduced hospital admissions for respiratory infections in children,” they add.

There is no evidence as yet that the polio vaccine works specifically against the new coronavirus, but the researchers are calling for immediate trials to test their theory.

Reasons for caution

Few medical interventions come without risks, and the polio vaccine is no exception.

In fact, the live oral vaccine “is actually being phased out” and replaced with an inactivated version, delivered by injection, says Dr Peter Hotez, dean of the US National School of Tropical Medicine.

This switch is partly because the live vaccine can lead to a full-blown case of polio in a small number of cases, and partly because even people who are successfully immunised will shed traces of live polio in their faeces. Once in the sewage system, the virus could enter the water supply.

“I think OPV is worth studying,” Hotez told Forbes, “but this has to be weighed against the risk of re-introducing live strains.”

Widespread vaccination has eliminated polio from all but two countries, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where the coronavirus pandemic is hampering eradication efforts. “In April, almost 40 million children missed their polio drops in Pakistan after the cancellation of the nationwide vaccination campaign,” The Guardian reports.

Most people infected with polio make a full recovery, but the virus can lead to muscle weakness, paralysis and death by suffocation in a small minority of cases.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?The Explainer Surge in cases of new variant H3N2 flu in UK and around the world

-

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 official

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 officialSpeed Read Dr. Ralph Abraham joins another prominent vaccine critic, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

-

This flu season could be worse than usual

This flu season could be worse than usualIn the spotlight A new subvariant is infecting several countries

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system