Exam U-turn: behind the algorithm that triggered A-level grades mayhem

‘Seeds of the policy disaster’ sown in letter sent by Gavin Williamson as lockdown was announced in March

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

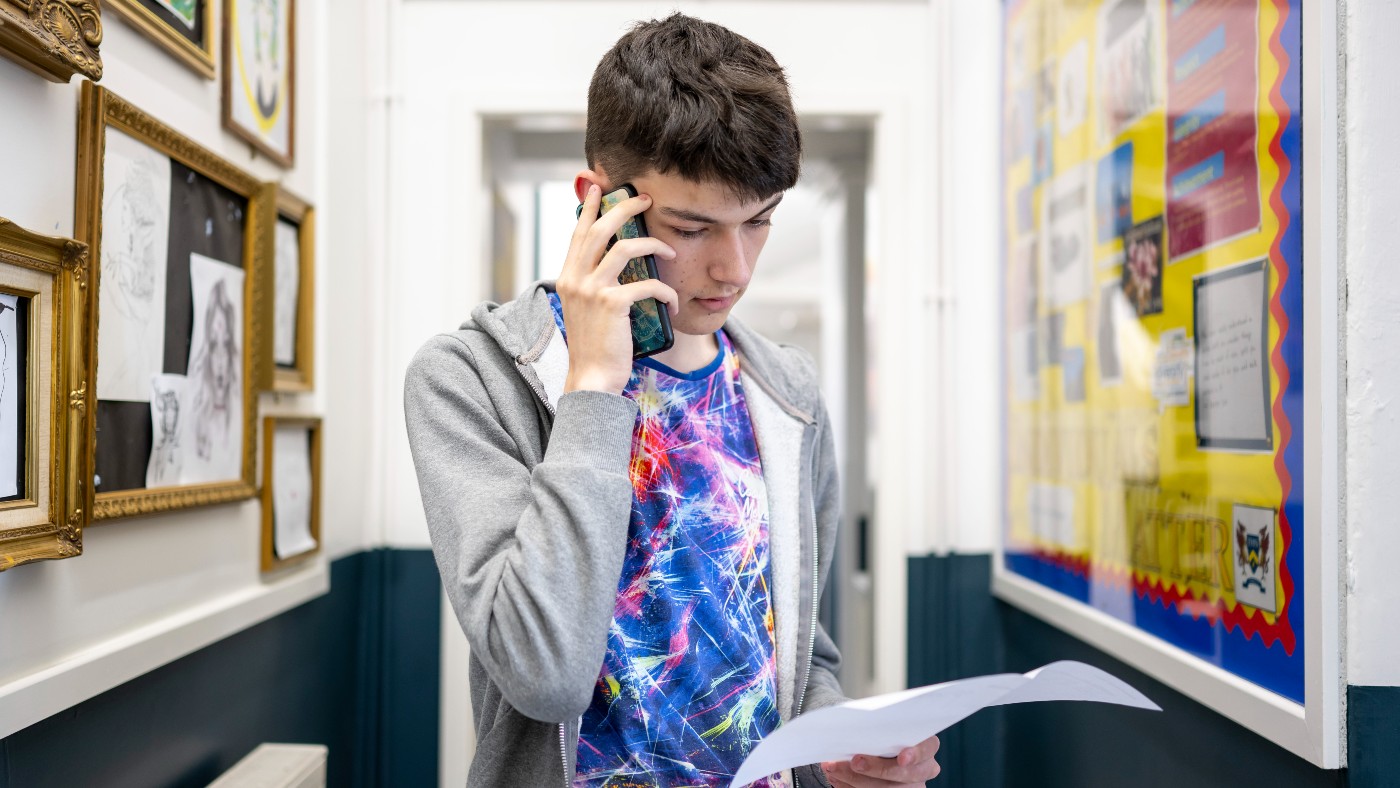

As anger erupted following the release of A-level grades last week, Prime Minister Boris Johnson insisted that the results were “robust”, “good” and “dependable for employers”.

But just days later, following Ofqual’s sudden withdrawal of the criteria for appealing grades, the government was forced into an embarrassing U-turn, with results now to be based on teachers’ predictions rather than those of a controversial algorithm.

The automated system was used in a bid to avoid what Education Secretary Gavin Williamson described as “rampant grade inflation” amid the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic and cancelled exams. But who came up with the algorithm, which could end up costing Williamson his cabinet job?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Unprecedented circumstances

The “seeds of the policy disaster were sown on the day the lockdown came into force”, when Williamson warned in a letter to Ofqual that avoiding grade inflation was a priority, The Times reports.

“Ofqual should ensure, as far as is possible, that qualification standards are maintained and the distribution of grades follows a similar profile to that in previous years,” Williamson told the exams regulator.

In other words, says the newspaper, “despite the fact that pupils would not sit exams, the government wanted to treat the class of 2020 like that of previous years”. A-levels were treated as the “‘gold standard’ of the education system and were not to be devalued”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But in “commissioning the exams regulator to take out an insurance policy in the form of its ill-fated algorithm”, this “desire to cap grade inflation went too far”, adds the BBC.

What went wrong?

At the education secretary’s request, the regulator’s statisticians set about devising a system for handing out grades that “didn’t allow exam results to go up from previous years”, explains Jo-Anne Baird, professor of educational assessment at Oxford University and a member of Ofqual’s advisory committee.

The problem was that “in the case of the class of Covid, the preoccupation with maintaining standards came at too high a price”, according to the BBC.

A total of 39% of the A-level results released last Thursday were downgraded, and “pupils in disadvantaged areas were disproportionately hit the hardest”, says NS Tech, a division of the New Statesman.

The algorithm predicted grades after being fed various bits of data.

“The first was the teacher’s predicted grade for each student based on their performance in class and the mock exams,” the news site explains. “But this was deemed insufficient on its own, so teachers were also asked to rank each student from highest to lowest in terms of their expected grade.”

“Schools threw themselves into the assessment task,” adds The Times, with department heads leading meetings where “teachers argued the case for their pupils”.

But, says the paper, “there was a catch” in the Ofqual system. A report released by the regulator last week revealed that teacher-assigned grades were only given priority in classes of less than 15 students - a system that favoured private schools with smaller class sizes.

By contrast, for pupils in larger schools, “grades were far more influenced by the school’s historical performance and their teacher’s ranking than their predicted grades”, NS Tech adds.

This discrepancy accounts for the disproportionate number of students from schools that do not usually send pupils to the UK’s top universities who saw their predicted grades aggressively downgraded.

Was a fairer system possible?

According to The Times’ science editor Tom Whipple, “making a fair algorithm is like trying to unboil an egg” - that is, “impossible”.

The problem, Whipple writes, is that “when people extrapolate from population data to make predictions about individuals... you can end up making all sorts of counterintuitive, surprising and sometimes absurd mistakes”.

This is what went wrong with an algorithm based so heavily on a school’s historical results, he argues. “Clearly, this will be unfair to exceptional children in unexceptional schools”, while “conversely, it will be overly kind to unexceptional ones in exceptional schools”.

Sam Freedman, CEO of non-governmental organisation Education Partnerships Group, agrees with this verdict. The algorithm was “inevitably going to hit outlier students who were at the top of the distribution in schools that haven’t had many high performers in the past”, he tweets.

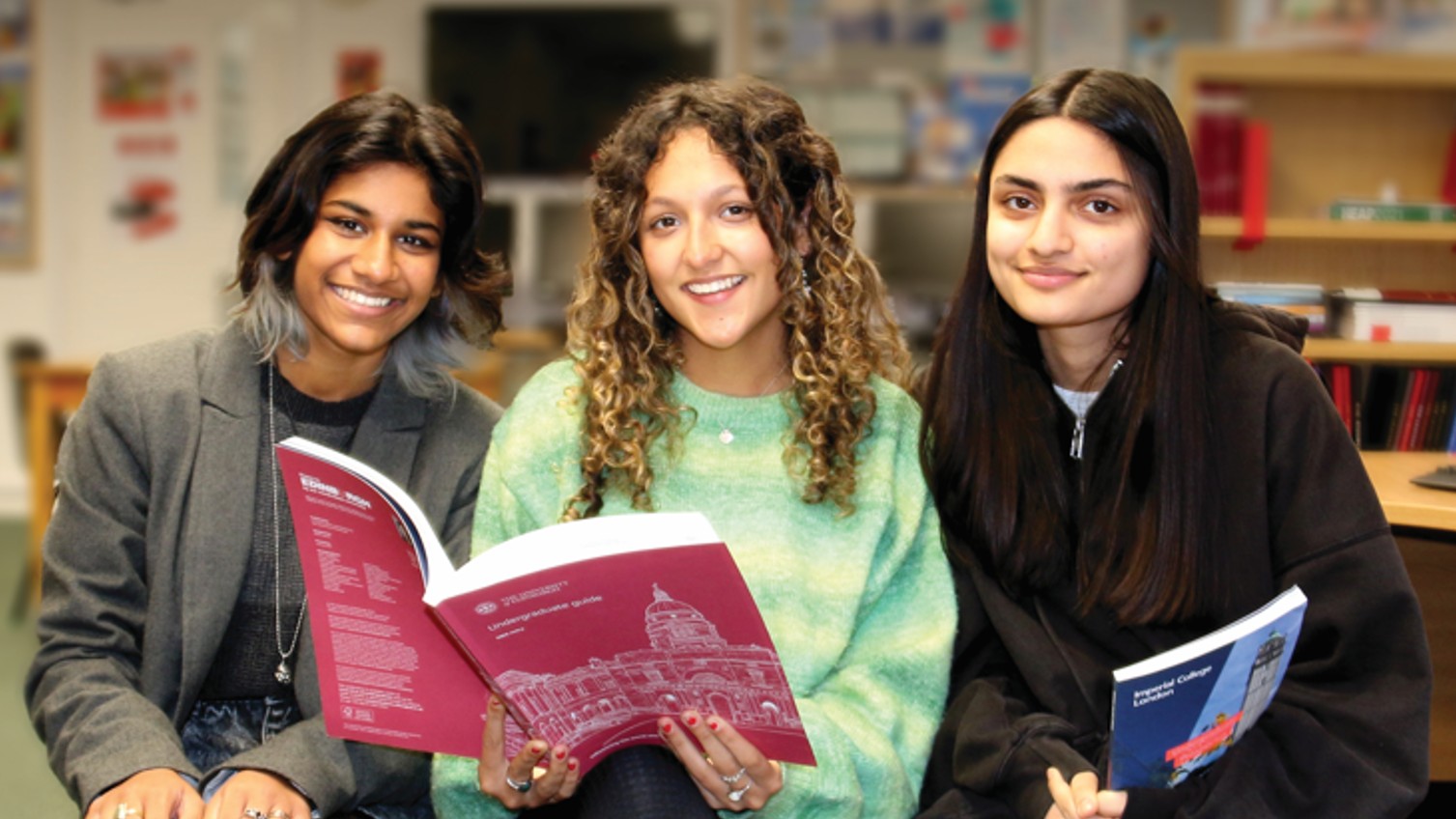

But, Freedman adds, the government’s decision to only use teacher’s predicted grades is also “unfair on pupils at schools who graded cautiously, unfair on past/future cohorts, and create[d] a lottery for uni places”.

And the U-turn may come too late for some students, with many universities saying courses for the next academic year are already full.

As for the algorithm, “statistics are by definition a way of representing many numbers in fewer numbers”, Whipple says.

“This is tremendously useful, but we need to know what it means: forgetting about the individual.”

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How will new V level qualifications work?

How will new V level qualifications work?The Explainer Government proposals aim to ‘streamline’ post-GCSE education options

-

Pros and cons of the International Baccalaureate

Pros and cons of the International BaccalaureatePros and Cons IB offers a more holistic education and international outlook but puts specialists looking to study in the UK at a disadvantage

-

The class of ‘23: worst off school-leavers yet?

The class of ‘23: worst off school-leavers yet?Talking Point The generation who lost critical months of schooling and weren’t able to sit their GCSEs now approaching a dysfunctional university

-

Breastfeeding for longer linked to better exam results

Breastfeeding for longer linked to better exam resultsSpeed Read New study suggests breast milk could help secure a child top grades in GCSEs

-

University life in the UK and US compared

University life in the UK and US comparedfeature Studying in the UK offers proximity to home, while US institutions tend to offer broader curriculum options

-

Pros and cons of GCSEs: is the exam system fit for purpose?

Pros and cons of GCSEs: is the exam system fit for purpose?Pros and Cons Tony Blair has called for ‘radical’ education reform but others want a more cautious approach

-

The pros and cons of going to university

The pros and cons of going to universityPros and Cons Record-high costs and competition leave A-level students questioning worth of a degree

-

Are too many people going to university in the UK?

Are too many people going to university in the UK?Today's Big Question Ministers urge school-leavers to consider alternative paths