What can Boris Johnson do to end the A-level ‘results crisis’?

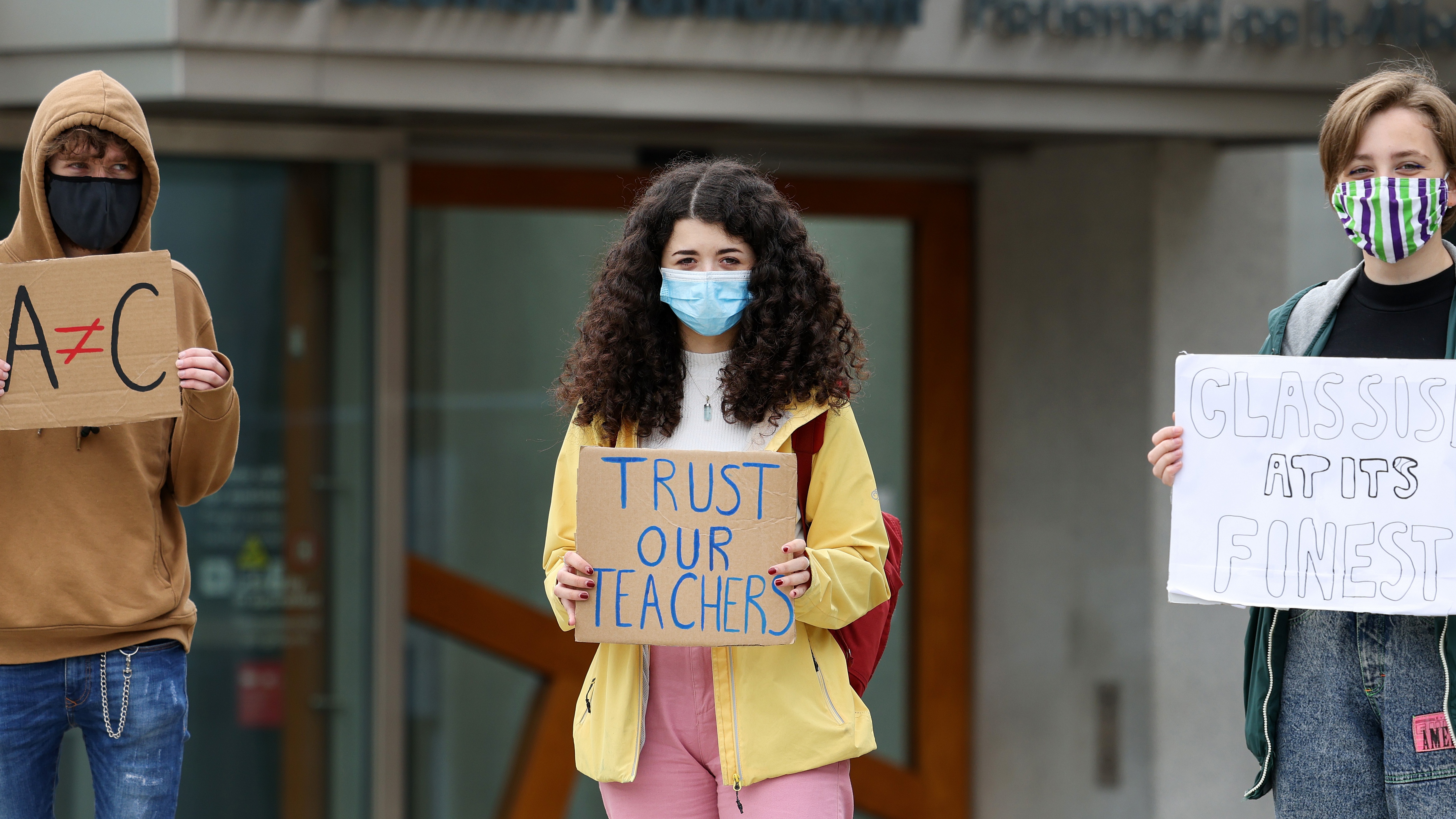

Teachers and pupils appeal for clarity over appeals process as universities say they cannot hold places

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pressure is growing on Boris Johnson to intervene in the A-level results catastrophe as the clock ticks down until the scheduled release of GCSE results on Thursday.

The prime minister is yet to comment on what Labour leader Keir Starmer has described as a “complete fiasco”, amid growing criticism of exam regulator Ofqual “over the statistical model it used to decide the grades”, the BBC reports.

The government is facing calls “to delay the [GCSE] results, change the grading algorithm or use the grades estimated by teachers, after complaints of unfair A-level results”, the broadcaster adds. So what are Johnson’s various options?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Delay GCSE results

Former Tory education secretary Lord Kenneth Baker has urged ministers to delay the publication of GCSE results until what the BBC describes as the “exam grades crisis” is resolved.

Baker, who introduced GCSEs, warned that the model used to standardise results this year following the cancellation of exams owing to the coronavirus pandemic was “flawed”.

“The A-level results have produced hundreds of thousands of unfair and barely explicable downgrades,” he said, adding: “If you are in a hole, stop digging.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A total of around 280,000 A-level results in England have been downgraded from teacher’s predictions - almost 40% of the total.

Delaying the release of GCSE results in order to “fix the moderation system” could sidestep a “new round of controversy expected for the Department for Education” later this week, says The Independent.

Remove the university cap

Oxford University has announced that it is “unable to offer further places to state school applicants affected by the grading fiasco”, owing to a cap on admission numbers imposed by the government, The Guardian reports.

The cap was unveiled in June, in an effort to prevent universities “taking a recruitment approach which would go against the interests of students and the sector as a whole”, the Department of Education said.

Universities in England have been told to cap the number of students “at their forecast growth plus 5%”, while universities in the rest of the UK are not allowed to “increase their intake of English students by more than 6.5%”, as TES (formerly the Times Educational Supplement) reported at the time.

Following the release of A-level results, Dr Mark Fenton, chief executive of the Grammar School Heads Association, told the BBC that “a great injustice has been done”, with “utterly baffling” outcomes for some students.

The “only fair outcome” would be to use the grades predicted by teachers and for the limit on university places to be lifted, he argued.

Some applicants to Oxford have been offered some good news, however. The university says it has “looked carefully” at all students who had failed to receive their target A-level grades and offered places to 300 – an increase of 5.7% compared to 2019, The Guardian reports.

Fix the appeal process

As ministers “struggled to mitigate anger at the moderation process”, the government last week announced that schools would be able to appeal against downgraded A-level results for free, the Financial Times says.

But although Ofqual released details over the weekend on how pupils could appeal against results, the process was “scrapped” just hours later, The Guardian adds.

“No explanation was given for the move, although Labour said that it undermined assurances given to pupils by Education Secretary Gavin Williamson about the appeals process,” according to the LBC news site.

Pupils and teachers had asked for clarity around the appeal process, after Williamson was contradicted by the exam regulator prior to the scheme being shelved.

The education secretary had promised a “triple-lock” commitment, meaning that pupils could use the highest result out of their teacher’s predicted grade, their mock exam, or sitting an actual exam in the autumn.

But Ofqual guidance said that if the mock result was higher than the teacher’s prediction, the latter would still dictate the final outcome.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT head teachers’s union, said the rules were being “written and rewritten on the hoof”, adding that “the people that are suffering are the thousands of young people who have seen their future options narrow and disappear through no fault of their own”.

Ditch the algorithm completely

In a further blow the the government, some members of the Ofqual board reportedly now want to ditch the system for “moderating” the predicted grades awarded by teachers.

An inside source told The Telegraph: “There is a significant view in Ofqual that there is no way forward. To do anything else would cause further haemorrhage in public trust in qualifications, and we are haemorrhaging it so much already.”

As LBC notes, “those concerns are likely to strengthen the hands of teaching unions who are pressing for teacher assessments as the only fair way forward”.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.