Divorce in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

From Henry VIII to the modern day, divorce has reshaped our notion of marriage

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world.

Divorce in 60 seconds

The right to divorce means the right to end a marriage and is available to citizens almost everywhere in the world. Today, divorce is only illegal in two states – the Philippines and Vatican City.

Most countries have what is known as "grounds for divorce", which sets out the reasons that a divorce would be permitted. Examples include sexual harassment, adultery, substance abuse, desertion and imprisonment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

During the 20th century, most European countries liberalised their divorce laws, shortening the period of separation required to file for a divorce, or adding circumstances under which divorce is permitted. However, some countries, such as Poland, still only allow divorce in the event of a "irretrievable breakdown of the marriage".

Divorce laws in Europe and Asia are generally fairly similar, while those in India are covered under the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955.

In the US, every state allows for "no fault" divorce, under which the dissolution of a marriage does not require a showing of wrongdoing by either party. Although US divorce rates have fallen in recent decades, only 57% of women who married for the first time between 1985 to 1989 made it to their 15th wedding anniversary, according to government census figures.

Before a divorce can be finalised, a couple must also agree on how to divide any shared money, what will happen to their shared property and where their children, if they have any, will live.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did it develop?

One of the most famous early divorces took place after Henry VIII in 1527 demanded the right to separate from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon - a request that was finally granted by the Archbishop of Canterbury. This followed an unsuccessful appeal to the Pope, based on the fact that Catherine was Henry’s brother’s wife prior to his death.

However, the first recorded divorces date back far earlier. According to The Journal of Hellenic Studies, the Ancient Athenians allowed divorce if signed off by a magistrate. These divorces were very rare, but not as rare as in Catholic Europe, where such separations were deeply frowned upon.

This religiously ordained approach to the end of a marriage led Henry VIII to break from Rome, after the Pope refused to allow the king’s divorce request.

The move towards liberalising attitudes towards divorce came with the Enlightenment. King Frederick II of Prussia was an early pioneer, setting divorce on the basis of mutual consent into law in 1752. This attitude influenced the law in neighbouring Austria, while in France, divorce was legalised following the French Revolution in 1799. Japan was a very early adopter of normalised divorce, allowing husbands to separate from their wives from as early as 1603.

In Britain, until the mid-19th century wives were considered to be under the economic and legal protection of their husbands, making divorce almost impossible. However, in 1857, divorce was taken out of the hands of the Church and made a matter for civil courts.

But the big change came in 1969, with the passing of the Divorce Reform Act, which allowed couples to divorce after they had been separated for two years (or five years if only one of them wanted a divorce).

A number of other European countries were surprisingly late to legalise divorce proceedings. In Italy, divorce was first introduced into law in 1970, while Ireland and Malta only approved divorce at referenda in 1995 and 2011 respectively.

How did it change the world?

The legalisation and liberalisation of divorce radically reshaped society’s notion of marriage and the family, while also offering people greater agency over their lives.

According to the book "Olympic Britain", written by researchers in the House of Commons library, divorce in the UK was rare prior to 1914 and was considered "a scandal, confined by expense to the rich, and by legal restrictions requiring proof of adultery or violence to the truly desperate".

However, as the law changed, attitudes to divorce became more liberal and women gained greater economic independence, the number of divorces rose to 50,000 per year in 1971 and then to 150,000 a decade later.

Global divorce rates have also increased over the past century, doubling between 1970 and 2008 from 2.6 divorces for every 1,000 married people to 5.5, according to research by US psychologists.

The study, by a team from the University of California, found that countries with higher divorce rates also tend to have a higher national income and a greater proportion of women in the workforce.

In an article for Psychology Today, social psychologist Bella DePaulo, who was not involved in the research, writes that divorce has had an "empowering, and sometimes even life-saving" impact for women, who are now able to "walk away from a bad situation".

Divorce has also heralded the decline of the traditional "nuclear family". The Pew Research Centre think-tank says that in the US, the number of children living in a single parent house rose from 9% in 1960 to 26% in 2014.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

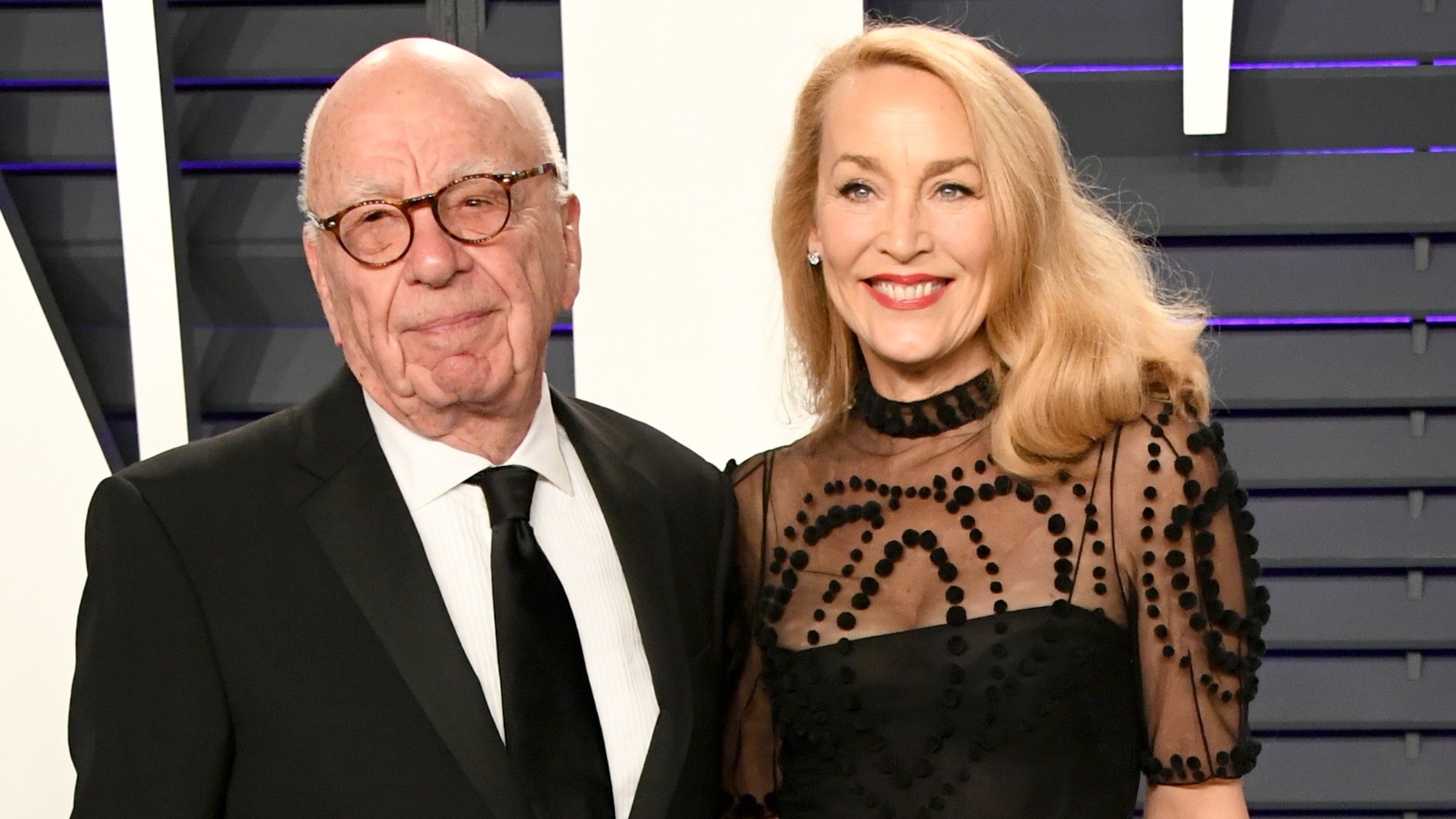

The most expensive divorces in the world

The most expensive divorces in the worldIn the Spotlight Media magnate Rupert Murdoch is to divorce for the fourth time

-

What are gender-critical beliefs?

What are gender-critical beliefs?Today's Big Question Judge-led panel ruled that such views should be protected under the Equality Act

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 44. Land registration

52 ideas that changed the world - 44. Land registrationIn Depth The legal registration of land allowed the building of mass property empires

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 40. Insurance

52 ideas that changed the world - 40. InsuranceIn Depth Managing and mitigating risk has been part of society since the dawn of humankind

-

Divorce laws overhaul to ‘end blame game’ for couples

Divorce laws overhaul to ‘end blame game’ for couplesSpeed Read Justice secretary announces legal overhaul to streamline divorce process