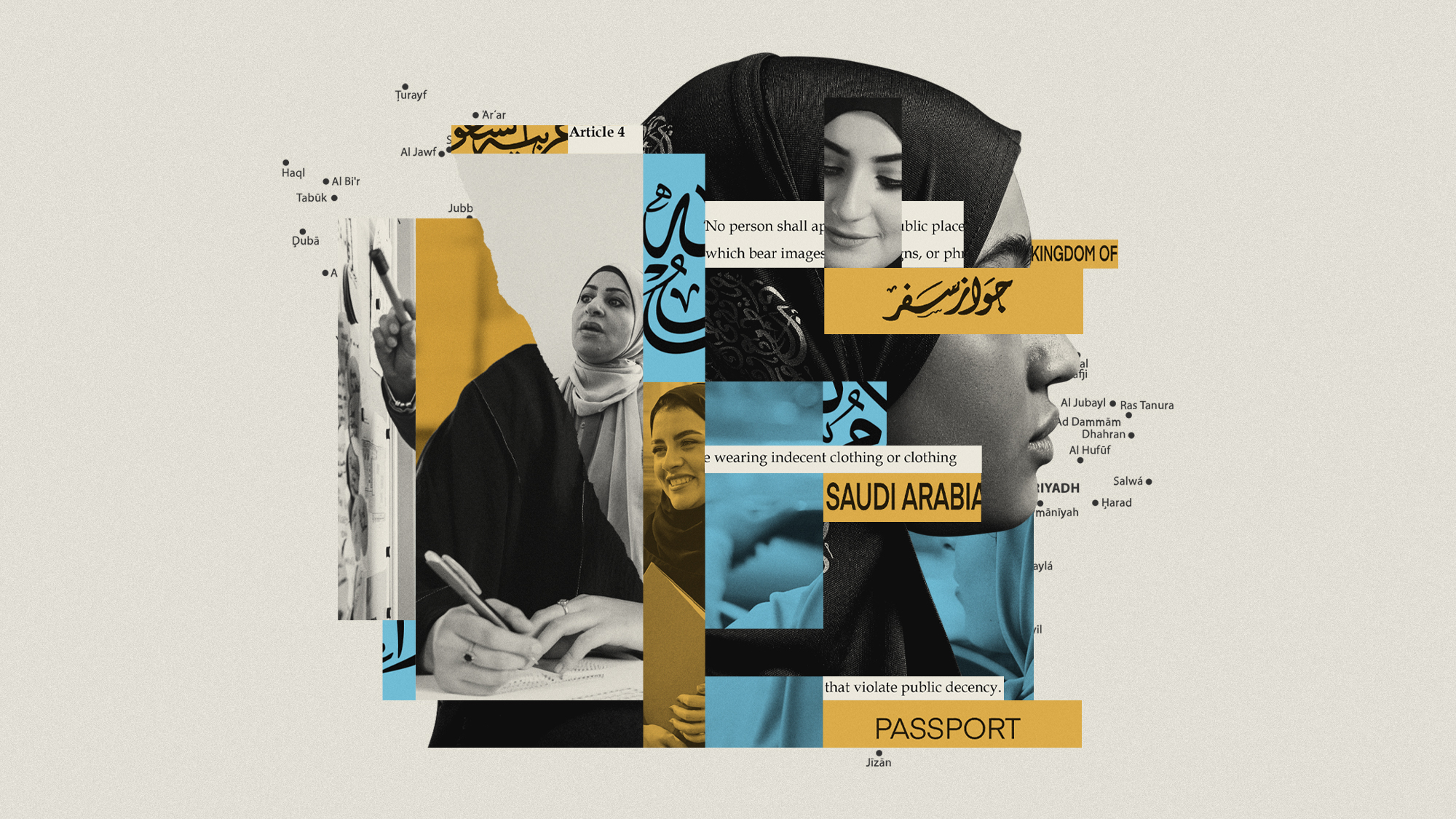

Saudi Arabia: the laws on what women can – and can’t – do in 2025

Rights for Saudi women are still far from equal but there have been big recent positive changes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The furore over the first Riyadh Comedy Festival has put the country’s human-rights record under fresh scrutiny, particularly for its treatment of women.

Some of the world’s most high-profile comics, including Dave Chappelle, Kevin Hart, Louis CK, Jimmy Carr and Jack Whitehall have been accused of helping “whitewash” the country’s repressive record by accepting huge fees to appear in the inaugural soft-power event in the Saudi capital.

One of the few female comedians on the bill, lesbian stand-up Jessica Kirson, has since apologised for taking part, telling The Hollywood Reporter she would be donating her fee to a human-rights organisation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While rights for women have steadily improved over the past decade under the modernising reforms of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia remains near the bottom of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Index, coming 132nd out of 148 countries in the 2025 report.

So what has changed for women in Saudi Arabia in recent years? And what restrictions do they still face?

Driving and travel

In 2018, Saudi women were allowed to drive in the kingdom for the first time. Restrictions on travelling abroad were loosened a year later, allowing women over the age of 21 to apply for a passport and leave the kingdom without the permission of a male guardian. And, since 2021, women have been permitted to go to Mecca to perform Hajj without a male relative, as long as they are travelling with other women.

Human-rights groups have highlighted instances of targeted travel restrictions, though, with Amnesty International claiming female activists have been subject to travel bans, both official and unofficial, in some cases lasting several years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Guardianship

The concept of guardianship, or wilaya, is deeply rooted in Islamic doctrine, taking different forms in different countries over time. In Saudi Arabia, this traditionally meant that every woman had a wali, a male guardian who makes decisions on her behalf – typically her father, and then her husband after marriage, although guardians can be brothers, sons, uncles or even male judges. This has meant that women were essentially treated as minors, in legal terms, for their entire lives.

Since 2019, however, the system has undergone some reform. Women aged over 21 no longer need their guardian’s approval to access healthcare, education and state services, take up a job or make their own medical decisions about pregnancy and birth. While the codification of the Personal Status Law (PSL) in 2022 introduced “significant reforms”, said LSE Blogs, “the guardian’s consent remained required in multiple areas”, including a woman’s right to get married, get divorced or leave certain institutions, such as a prison or a domestic-abuse shelter.

In February, Saudi Arabia’s Official Gazette published additional details on the implementation of the law. These address the matter of adhl (unjust prevention of a marriage), and grant women the right to seek the transfer of guardianship if a male guardian is negligent or unjust.

Marriage

Saudi Arabia has made some efforts to reform marriage-related laws but the influence of guardianship and traditional customs remains significant.

Touted as a “progressive” change, the PSL, which was introduced on International Women’s Day in 2022, actually codifies many traditional Islamic rules, including those on marriage and divorce, into law. While this improves equal treatment by preventing judges from using their own individual interpretation of Islamic principles to make rulings on family matters, it nevertheless “enshrined discrimination against women rights into the legal code”, said Rothna Begum of Human Rights Watch. So now, women legally need the permission of a male guardian to marry or divorce, and married women are required by law to obey their husband “in a reasonable manner” or risk losing their right to financial support. Neither husband nor wife can abstain from sex without their spouse’s consent.

The law also set the minimum age at which women can marry at 18 (although courts can authorise the marriage of a younger woman if she is deemed mature enough to give consent), and judges can allow a woman to marry a man of their own choice if their guardian’s objection is “unreasonable”. Husbands are no longer allowed to verbally divorce their wives but they can still unilaterally divorce their wife, while a wife who wants to end a marriage must petition a court “on limited grounds”.

Custody and guardianship of children

Historically, the Saudi approach to child custody after divorce has been inconsistent. Under Islamic rules, the father remains the legal guardian but the mother retains custody until a boy is seven or a girl reaches puberty. However, judges tended to interpret the rules very differently, resulting in unpredictable decisions that were often more unfavourable to mothers.

The PSL has ironed out those inconsistencies. It “codifies the classical Islamic rule on parental responsibility, designating the father as the guardian of the child” but giving mothers an assumed right to primary custody, academics Beata Polok and Zubair Abbasi wrote for the LSE Religion and Global Society newsletter. Children of either sex can stay with the custodial parent until they are 15 and can then choose which parent to live with, according to the Oxford Human Rights Hub.

The PSL also overrides a judicial tradition which tended to remove children from their mother’s custody if she remarried – the new legislation allows a woman to retain custody if her remarriage is not deemed to be against the child’s interest, according to the Oxford Human Rights Hub.

Mothers with primary custody of a child can now apply for a passport for their child or for a grant to take them out of the country for up to 90 days, without needing consent from a male guardian.

Education

Women’s education has undergone significant transformation over the past few decades, influenced both by government policies and shifting cultural norms. Education is a key part of Vision 2030, and the literacy rate for Saudi women aged 15-24 was close to 100% in 2017, compared to 57% in 1992, according to Unesco figures reported by Pakistani newspaper Dawn.

Female students account for just over half of those enrolled at Saudi universities, and Saudi women have “forged ahead in all areas of academia, from administration and teaching to research”, said Arab News.

Gender segregation is enforced throughout the education system, although a handful of universities offer co-educational courses where male and female students share classrooms, although living facilities remain strictly single-sex.

Employment

In 2018, women made up only 15% of Saudi Arabia’s total labour force. By 2024, that number had reached 34.5%, propelling the kingdom beyond the targets set in Vision 2030, said Arab News. The “remarkable increase” in female economic activity has been made possible by “proactive government policies”, together with rising educational achievement and increased demand for women workers, said the Atlantic Council.

Changes since 2017 include allowing women to apply for jobs and start their own businesses without a guardian’s consent – and the 2018 decision to allow women to drive has opened up new opportunities. The 2018 Anti-Harassment Law was another “major milestone”, noted UK-based Middle Eastern news site Amwaj.media. Workplace harassment can now result in significant penalties, including prison sentences.

However, the female workforce remains “largely concentrated in caregiving and education”, and gender segregation limits women’s access to leadership roles and networking opportunities. “Efforts have largely centred on boosting workforce numbers, rather than tackling the deeper, systemic inequalities that persist for females in the Kingdom.”

Sport

As recently as 2018, women and girls were barred from taking part in sports in schools or even watching sports in stadiums. But since then the change in women’s sports has been “profound”, said Fortune.

Take football: more than 70,000 girls participate in the nation’s female school soccer league, which launched three years ago, according to Adwa Al-Arifi, assistant minister for sport affairs in Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Sport. The Saudi Women’s Premier League has 10 teams, with players free to choose whether or not to wear a hijab while competing. This year’s season will be “broadcast domestically and worldwide for the first time”, said Reuters, and coincides with the launch of the first dedicated 24-hour women’s sports TV channel in Saudi Arabia.

“Investing in women’s sports sends great signals to both the domestic Saudi population and the rest of the world that they are doing great stuff for women,” Stanis Elsborg, head of Play the Game – an initiative promoting democracy, transparency and freedom of expression in world sport – told DW. But this “then leads to more or less or no discussion about the continued human rights abuses of women in the country”.

Social life and clothing

Life for Saudi women has “rapidly” transformed and the country has made “historic strides” in terms of female access, without a male escort, to public spaces, including concerts, cinemas and sporting events, ABC News said.

The black abaya (a full-length, loose-fitting robe) and niqab (full-face veil) were once emblematic of the restrictions placed on Saudi Arabian women, and those who strayed from this dress code were subject to harassment from religious police. However, Crown Prince bin Salman has repeatedly emphasised that the abaya and head coverings are not mandatory. In a 2018 interview with US news programme 60 Minutes, he said that Saudi men and women alike should wear “decent, respectful clothing” in accordance with cultural and religious norms, but that, beyond that, clothing choice was “entirely left for women”. That perspective is reflected in a public decency law introduced in 2019, which requires “modest” dress for both sexes but only specifies “loose clothing” that covers both elbows and ankles.

The vast majority of Saudi women continue to wear the abaya and a head covering. Patterns and colours are becoming a more common sight, as are open abayas worn over Western-style clothing.

Footwear choices are “generally unrestricted”, said Fact Crescendo, and “make-up is widely accepted, with an emphasis on subtle, sophisticated looks”.

There is, however, “no verifiable evidence” from official Saudi government sources, news outlets, or bin Salman himself about a further relaxation of clothing rules for women, despite claims that “have circulated about a new announcement in 2025”.

Personal data

Technology has historically been used in Saudi Arabia to monitor and control women’s movements, according to the non-profit European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights. Since 2021, all Saudi citizens have had control over their personal data, in theory empowering women to manage their information and make informed decisions about its use. But last year Freedom House said internet users of both sexes continue to face “extensive” censorship and surveillance, and women’s rights activists continue to be jailed for online posts.

Elizabeth Carr-Ellis is a freelance journalist and was previously the UK website's Production Editor. She has also held senior roles at The Scotsman, Sunday Herald and Hello!. As well as her writing, she is the creator and co-founder of the Pausitivity #KnowYourMenopause campaign and has appeared on national and international media discussing women's healthcare.

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?Talking Point The latest slew of embarrassing emails from Fergie to the notorious sex offender have put her daughters in a deeply uncomfortable position

-

Trump, Iran trade threats as protest deaths rise

Trump, Iran trade threats as protest deaths riseSpeed Read The death toll in Iran has surpassed 500

-

Israel-US 'rift': is Trump losing patience with Netanyahu?

Israel-US 'rift': is Trump losing patience with Netanyahu?Today's Big Question US president called for an end to Gaza war and negotiated directly with Hamas to return American hostage, amid rumours of strained relations

-

Blue Origin all-female flight: one giant leap back for womankind?

Blue Origin all-female flight: one giant leap back for womankind?Talking Point 'Morally vacuous' celeb space crew embody defeat for feminism

-

Gaza: the killing of the paramedics

Gaza: the killing of the paramedicsIn the Spotlight IDF attack on ambulance convoy a reminder that it is 'still possible to be shocked by events in Gaza'

-

US accuses Sudan rebels of genocide, sanctions chief

US accuses Sudan rebels of genocide, sanctions chiefSpeed Read Sudan has been engaged in a bloody civil war that erupted in 2023

-

Has the Taliban banned women from speaking?

Has the Taliban banned women from speaking?Today's Big Question 'Rambling' message about 'bizarre' restriction joins series of recent decrees that amount to silencing of Afghanistan's women

-

Africa's renewed battle against female genital mutilation

Africa's renewed battle against female genital mutilationUnder the radar Campaigners call for ban in Sierra Leone after deaths of three girls as coast-to-coast convoy prepares to depart

-

Miss Universe 2023: win for inclusion or nothing to celebrate?

Miss Universe 2023: win for inclusion or nothing to celebrate?Talking Point Beauty pageant included mothers, plus-sized models and trans women – but fails to distract from global conflict