Will the 1922 Committee change its rules to oust Liz Truss?

‘As many as 100 Conservative backbenchers’ may already have penned letters of no confidence in the prime minister

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The dramatic sacking of Kwasi Kwarteng last week further intensified the pressure on the prime minister after a tumultuous few weeks.

But even before Jeremy Hunt was appointed chancellor on Friday, the 1922 Committee’s executive had received “a pile” of letters of no confidence in Liz Truss’s premiership, The New Statesman reported.

An “unconvincing” press conference in No. 10 on Friday afternoon “did little to ease” the concerns of the committee of backbench Conservative MPs over Truss’s leadership. These had grown louder as the “political crisis and market turmoil sparked by her fiscal plans” led the PM to perform a major U-turn on freezing corporation tax, said Reuters.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Truss “looked close to breaking point” during the “brief” televised conference, said The Observer’s political editor Toby Helm, who added that Truss could hand in her resignation “in the coming days” to “leave with some dignity, without being forced out by her party”.

But “the route to removing her as prime minister, should it come to that, is not straightforward”, Reuters noted. The 1922 Committee, which determines the rules around a leader’s selection and removal, could play a crucial role in the coming days.

What is the 1922 Committee?

The 1922 Committee’s main function is to keep the leadership of the party informed of the mood of Conservative backbenchers.

The group meets every week when Parliament is in session and gives backbench Tory MPs the chance to air their concerns, report on constituency work and coordinate legislative agendas.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The 1922 group “assesses, organises and ballots on leadership challenges – meaning its power, when called upon, can be huge”, said The Sun.

Committee members elect their chair, who is usually a senior MP and has considerable influence within the parliamentary party. It is currently led by Graham Brady, the MP for Altrincham and Sale West.

The committee’s chair is also “sometimes the person who presents unpopular leaders with their marching orders, when the troops have lost faith”, said the BBC’s parliamentary correspondent Mark D’Arcy.

The committee’s power has been demonstrated several times in recent years, when motions of no confidence were brought against Theresa May in 2018 and Boris Johnson in June this year. Despite both former prime ministers surviving their separate leadership challenges, they each went on to resign shortly after the votes.

Iain Duncan Smith’s reign as Tory leader also ended following a confidence vote, after then 1922 chair Michael Spicer received enough letters from Tory rebels to trigger the contest back in 2003. Duncan Smith was ousted the following day.

How did the name come about?

Formally known as the Conservative Private Members’ Committee, the colloquial name of the group is often assumed to come from a meeting of Conservative MPs that took place on 19 October 1922.

The gathering successfully ended the party’s then coalition with the Liberals, bringing down the government of David Lloyd George. The Tories won the subsequent general election.

However, the group was actually set up the following year by MPs elected in the 1922 general election, in order to “facilitate cooperation within the party”, according to the parliamentary website.

Could the committee oust Truss?

If MPs do decide they would be better off with a different leader in No. 10, the 1922 Committee can play an important role in registering their discontent.

Any Tory MP who thinks a PM is no longer fit to hold the office, or can no longer command the party, can send in a letter to the 1922 Committee calling for a vote of no confidence. MPs can do this either by handing a letter directly to Brady, or following a rules update in December, by emailing him registering their loss of confidence.

If at least 15% of the party’s MPs submit letters to Brady, then a confidence vote “must be held”, according to the committee’s rules. In that instance, “a simple majority” is all that’s needed for a vote to be won, said the BBC: “only one more MP needs to vote in favour than the number voting against it”.

The 1922 Committee has long played a “key role” in Conservative Party history, said Bloomberg, and has brought down more than one prime minister. While the downfall of Margaret Thatcher in 1990 was prompted by the departure of her deputy prime minister Geoffrey Howe, it “was her ministers’ advice that she wouldn’t survive a second 1922 Committee ballot on her leadership” that led to her resignation.

The committee also caused problems for John Major, who the group felt “embodied Tory opposition to closer ties with Europe”, the news site continued. And while David Cameron sought in 2010 to “dilute” the committee’s influence “by opening up its membership”, he “failed” and Brady’s reign as chair began.

But “facing such a vote does not guarantee a prime minister’s downfall and even losing it does not force him or her out immediately”, said The Times. Indeed, Johnson won the support of 211 of his MPs in June, equating to 41% of his parliamentary party, with 148 of his MPs voting to oust him.

The committee’s current rules mean that Truss couldn’t face a confidence vote until September next year, having only become leader of the party last month. But the group “could remove that restriction if there were sufficient pressure from within the party”, said Reuters.

And “there are other routes”, added The Observer’s Helm. According to MPs, if at least half of Conservative MPs submitted letters to Brady saying they wanted Truss out of No. 10, the chair “would then feel obliged to visit the PM and tell her the game was up”.

Could the 1922 Committee change its rules?

The 1922 executive “is ready to suspend the rule that currently prevents a vote against Truss within a year of taking office”, said The New Statesman – and “there is nothing to stop” them from doing so to “allow an immediate challenge”, said The Observer’s Helm.

The Times reported that the Tory party’s “powerbrokers” took part in “secret discussions about ousting” Truss during what was described as a “grim” virtual meeting on Friday evening. Ministers in attendance “questioned the point of her staying in office” and “are thought to have concluded that Truss’s departure was increasingly likely”.

Brady “will act only if a significant number” of letters have been submitted, the newspaper continued. That could well be the case – “as many as 100 Conservative backbenchers” may already have penned letters to Brady calling for a confidence vote, the i news site reported.

Should Truss leave office, a replacement would rapidly need to be elected.

“No one in the party wants to stage another full-blown contest” like the leadership race that took place this summer, Helm continued. So the “quickest and easiest way” to determine a replacement would be “for Tory MPs to draw up a shortlist of two” who would “agree between themselves who would be PM and who deputy”, without putting a vote to Tory party members.

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Three consequences from the Jenrick defection

Three consequences from the Jenrick defectionThe Explainer Both Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage may claim victory, but Jenrick’s move has ‘all-but ended the chances of any deal to unite the British right’

-

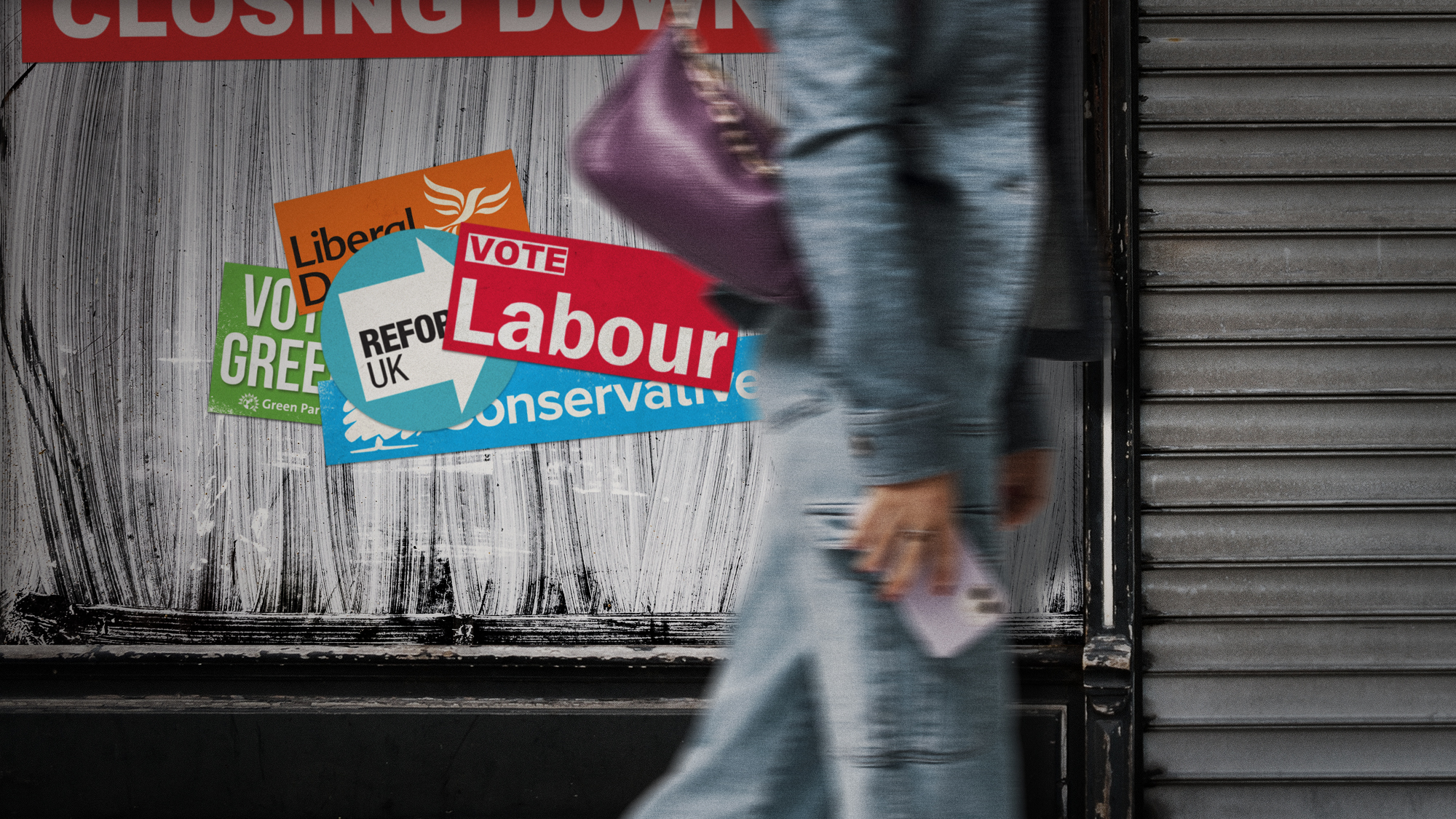

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conference

The MAGA civil war takes center stage at the Turning Point USA conferenceIN THE SPOTLIGHT ‘Americafest 2025’ was a who’s who of right-wing heavyweights eager to settle scores and lay claim to the future of MAGA

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

What does the fall in net migration mean for the UK?

What does the fall in net migration mean for the UK?Today’s Big Question With Labour and the Tories trying to ‘claim credit’ for lower figures, the ‘underlying picture is far less clear-cut’

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?