Chanel's special effects studio: Maison Lesage

The Chanel-owned institution of handwork and fine stitchery

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I first meet Hubert Barrère, the charismatic artistic director of Maison Lesage, in Venice at a special exhibition space that is best described as a Chanel planetarium: a dimly lit room where spotlights shine on spectacular swatches of embroidery that sparkle like mini meteor showers frozen in time. Each embroidery sample – a snippet of a Chanel couture dress – is framed behind a square of white card and presented as a finished oeuvre; like luminescent paintings comprised of sequins, beads, pearls, flecks of gold, silken thread, raffia and much more besides.

The effect is quite mesmerising, and Barrère, who has never seen his designs and the workmanship of his team presented in such a way, is quite taken aback by the twinkling display. “It’s like seeing something completely new,” says the designer. “I know these patterns – I devised them – but like this, well, it’s like entering into a magical universe.”

The Lesage exhibition in Venice is part of the very first ‘Homo Faber’ event – a colossal show that gathers from across Europe more than 400 craftspeople who create masterpieces by hand. These artisans, who often work in the shadows, are the lifeblood of luxury brands. Showcasing their skills in mini workshops throughout the Fondazione Giorgio Cini arts centre on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore are bookbinders from Smythson, watch-dial enamellers from Vacheron Constantin, gem setters from Van Cleef & Arpels, saddle makers from Hermès, and independent specialists such as tapestry and fine art restorers, not forgetting champions of niche curiosities, such as Frenchman Charles Roulin, who creates spectacular carvings on folding knives.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lesage has one of the biggest exhibition spaces at Homo Faber, since its name has been tied to the fine art of haute couture for decades. At Lesage, needlework knows no bounds, which is why this legendary name in fashion, founded by François Lesage in 1924, is arguably the world’s most famous embroidery house. Acquired by Chanel in 2002, Lesage is part of the maison’s Paraffection (‘for love’) subsidiary, which counts a number of specialist Métiers d’Art workshops; these include feather-makers Lemarié, pleating atelier Lognon, bootmaker Massaro, milliner Maison Michel and jeweller Goossens.

Chanel’s initiative, much like Homo Faber, though more prolonged and distinct, aims to promote and preserve the savoir faire of artisans through its acquisition of Métiers d’Art firms producing couture goods for Chanel and other prestigious houses.

Barrère is photographing his favourite exhibits. His passion for embroidery is palpable, and his personal style is pure fun: he has short, platinum- blond hair and a predilection for geek-chic specs and zany trainers. As he explores the exhibition, he namechecks the Chanel collection that sparked each sheet of scintillating needlework. One sequinned pattern redolent of pinwheel fireworks is cast in the colours of the French flag; the highly intricate design was used to cover an entire jacket presented at Chanel’s Fall 2018 couture show in Paris, themed on the capital city itself as a direct tribute to the birthplace of couture and the French craftspeople who have maintained its authority as a leader of innovation throughout the centuries. Another decorative swatch is covered in beige strips of wood that have been cut like pencil shavings with multicoloured hand-dyed edges. For the catwalk, these ‘eco embellishments’ were used to create a scale-like pattern on the sleeves and under-skirt of a powder blush dress presented at Chanel’s Spring 2016 couture show, which took place at the capital’s landmark Grand Palais.

For this same collection, the Lesage atelier created embroidery out of wood chips, which it recast as beads, frills and even mosaic ‘tweed’. “The process is a va et viens between us and Karl [Lagerfeld, Chanel’s celebrated artistic director],” says Barrère, who has led Lesage since 2011. “We at the Métiers d’Art [companies] have great creative liberty, much more so than the haute couture ateliers that are more guided. Karl sends us his sketches, and I propose different ways of bringing to life his vision. I work with the team at Lesage to develop new techniques and ways of expressing light, colour and texture. To be free to do this is truly unique.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Lesage is a company founded on the principle that embroidery must advance the more subtle synergies between cloth and embellishment while maintaining the specific design codes of each luxury house; the idea being that decorative techniques should be innovative, surprising and visually enlightening, as a means of enhancing or shaping the silhouette of an haute couture design – or indeed that of a ready-to-wear garment, since Lesage works across all of Chanel’s annual collections (including accessories) as well as embroidery commissions for other luxe labels.

The house was originally founded in 1868 by Albert Michonet, who supplied embroidery to Charles Frederick Worth, couturier to Empress Eugénie. During the First World War, Michonet’s business hit on hard times and was subsequently unable to capitalise on the newfound optimism of the early 1920s, a time of great daring in European style and culture thanks to the birth of Surrealism and the avant-garde.

Albert Lesage, an entrepreneur with an eye for fashion, bought the business in 1924. He and his wife Marie-Louise Favot,a talented embroiderer who had previously worked for Vionnet, soon established Lesage as a needlework authority, producing embroidery for visionary designers such as Elsa Schiaparelli. They weathered the financial crash of the ’30s and the austerity of the ’40s, while their son François lived in Los Angeles, having moved there at the age of 19 to learn English. François, who became well connected within the French expat community thanks to family friend and film star Charles Boyer, began to pitch his designs to Hollywood studios. He soon set up his own embroidery atelier on Sunset Boulevard, where he created gowns for Marlene Dietrich, Lana Turner, Lauren Bacall and Ava Gardner.

François returned home to helm Lesage in the early ’50s when his father passed away, bringing a fresh new ‘Californian’ dynamism to the business, experimenting with new materials, trimmings and textures. His customers were fashion’s pre- eminent free-thinkers, among them Cristóbal Balenciaga, Pierre Balmain and Christian Dior, and later Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Lacroix and Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel. For Saint Laurent’s SS88 collection, he created the couturier’s famous Van Gogh-inspired Iris and Sunflowers jackets, each one comprised of 450,000 sequins. Designers dubbed him ‘Monsieur La Féerie’ (‘Mr Fairytale’) but the humble Lesage chose to describe himself as ‘the Switzerland of style’, unwilling to entertain the rivalry that existed between fashion houses.

As for Hubert Barrère, his entry into Lesage was seemingly written in the (Chanel) stars. Born in Bretagne, he initially studied law before the pull of fashion became too great. “I think I was drawing dresses before I could speak,” laughs the jovial designer. He moved to Paris to pursue a degree in fashion at the École de la Chambre Syndicale, a breeding ground for great talent including Saint Laurent, André Courrèges, Valentino Garavani, Issey Miyake and Karl Lagerfeld.

“As a student, I could not afford to work as a stagiaire [unpaid intern] for a big fashion house,” explains Barrère, who eventually took a minimum wage internship at another, lesser-known embroidery house, where he undertook a variety of projects in order to hone his needlework skills. One task proved to be more challenging than he expected, so he approached Maison Lesage for guidance.

“I was working on an embroidery inspired by the Opéra de Paris. I had arranged to meet someone at Lesage who had offered to help me, but while I was waiting in the corridor, Monsieur Lesage himself asked to see my work. He gave me lots of advice and helped me to pick out the right pearls and sequins. He was so kind and generous. After this encounter, I made a point of staying in contact with him. I got to know his wife and kids; we became friends. I never worked with him, but he liked to hear how my career was progressing,” says Barrère of the avuncular Lesage founder, who, in 1992, set up his namesake school on Paris’ rue de la Grange Batelière to ensure the art of embroidery would be passed on to the next generation. The École Lesage is today considered one of France’s great bastions of creativity.

The young Barrère would progress within the ranks of fashion quickly, too: he set up his own business making corsets for top fashion houses including Alexander McQueen, John Galliano (then at Dior) and Stella McCartney; then, in 1997, Barrère became the creative director of Hurel, an esteemed embroidery house which, at the time, also collaborated with Chanel.

When Monsieur Lesage became gravely ill in 2011, the veteran designer, who worked into his eighties, expressed his desire for Barrère to assume the mantle of leadership at Lesage. The role came as a big surprise: “At that point I had been working with Chanel for 20 years [at Hurel and other houses], but honestly I wasn’t prepared for such news. Lesage is an institution.” Barrère’s move was bitter-sweet: “I arrived at Lesage on the December 1, 2011. There was no settling-in period, because Monsieur Lesage passed away in his sleep the evening before my arrival. All the women at Lesage were mortified: he was like a father figure, their mentor, le maître brodeur.”

Barrère nonetheless proved to be a worthy heir. One his first projects was to provide embroidery for Chanel’s Cruise 2013 catwalk, held in May 2012. The collection, which Karl Lagerfeld conceived as a futuristic spin on 18th-century Versailles dress, included embroidery that combined traditional handiwork with high-tech fabrication. One pouffy miniskirt crafted from metallised/gold-embossed plastic appeared to be encrusted with soft pink seashells, wavy green algae and delicate coral – the tiny scallop shapes were in fact fashioned from gathered pink latex, which Lesage experts combined with waves of white lace ribbon along with glass green beads, diamanté-encrusted gems, and thousands of tubular pink and gold sequins.

“A threaded needle is la voie royale of embroidery: you can do anything with it,” says Barrère, who I have come to visit at Lesage’s atelier in Pantin, on the outskirts of Paris. The modern, but otherwise nondescript, building is also home to a handful of Paraffection firms, including Goossens, Lemarié and Maison Michel.

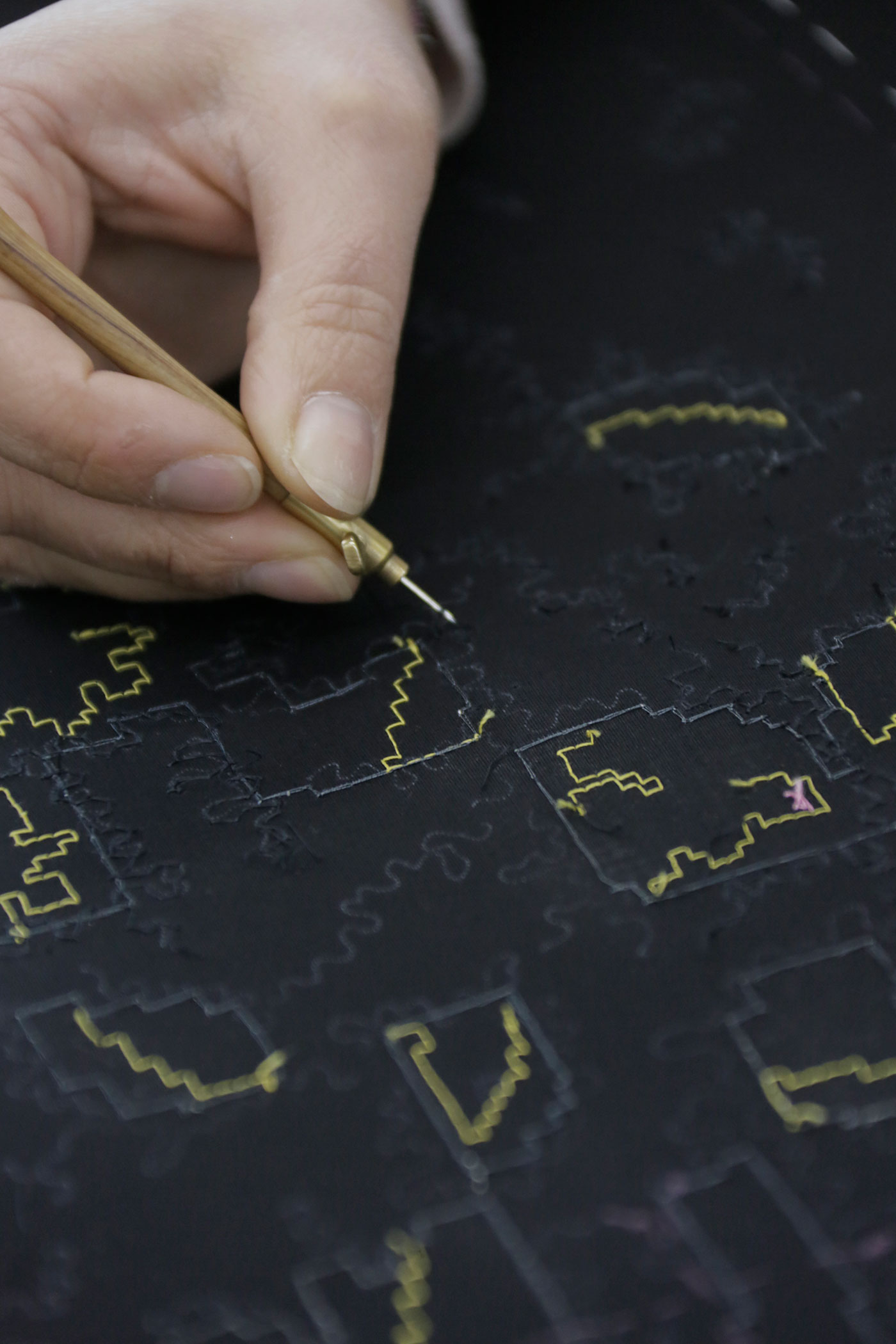

The mood is quiet and reverent in the airy, open-plan spaces of the Lesage atelier as embroiderers patiently work on new patterns for the 2018/19 Métiers d’Art collection, due to be presented at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on December 4. It’s early November, and week one of the production cycle: a time of expeditious experimentation. Barrère’s own drawings and ideas are presently being realised by his team, who work with a needle and a Lunéville hook – a 19th- century invention that takes its name from the Lorraine town where it was conceived.

Originally devised for chain-stitch embroidery, the traditional wooden-handled tool, unchanged for over two centuries, enables faster and more precise work using beads and sequins on ultra-light materials, though patterns are formed upside-down on fabric. Every so often, the Lunéville hand-workers flip their frames to inspect the glittering forms that are hidden from view as they work. There are blue and green gem-encrusted collars and golden swirls of matt sequins taking shape beneath their fingertips. Barrère instructs one experienced brodeuse to remove a row of gold sequins from her complex design. “It has to be powerful, but lean and direct,” he explains. Ten minutes later, he’s delighted with the result: “That’s perfect – it’s ready to go!”

Typically, the Lesage team – anything from 35 to 70 hand-workers, depending on workflow – must deliver embroideries for each collection within four weeks of receiving Lagerfeld’s croquis. These sketches are characteristically fluid and undetailed, leaving room for Barrère to dream up the decorative elements that will bring the veteran designer’s chosen theme to life; sometimes this is a mood rather than a precise narrative. Once Lagerfeld is happy with the embroidered motifs, Lesage’s drawing experts have the assiduous job of working out how to transfer these patterns to toiles (canvas prototypes) and paper accessory shapes (including hats and bags). In effect, these artists are the puzzle-makers who must reconcile embroidered patterns with the architecture of the collection.

Armed with these final stitchwork ‘road maps’, needleworkers complete embroidered panels piece by piece. The finished segments are then sent back to Chanel’s haute couture studio at 31, rue Cambon, where seamstresses apply them to the collection’s final tailleur and flou (tailoring and dressmaking) showpieces. The upper floor of the Pantin workshop is dedicated to Lesage’s tweed department. All of Chanel’s iconic fabric is conceived here, painstakingly made on handlooms using threads of all descriptions: metallic, latex, denim, wool, ribbon; some are flat and thick, others texturised, knobbled, wrinkled, embossed, frayed or twisted – the possibilities are endless. Tweed patterns are reinvented each season by Lesage, and the samples are sent to Chanel production sites for large-scale manufacture in Pau, southwest France.

The Pantin studio also acts as a rich repository of hand-sewn treasures: its basement stores 75,000 archival pieces of couture embroidery dating back to the mid-19th century. “The word ‘archive’ is deceptive because it sounds outdated; these embroideries are still so very modern,” argues Barrère. “There are many techniques that continue to inspire us: the classic vermicelli stitch, which we use extensively, allows us to make little waves of pearls or sequins with varying intensity, depending on how standout we want to effect to be. Then there’s the point de grains (seed stitch) or la broderie Richelieu, named after France’s famous cardinal and minister to Louis XIII, who had the king’s artisans adopt Venetian hemstitching and cutwork techniques. So, you see, embroidery is a fantastic window to the past, but it does not lose relevance, especially when you apply classic methods of practice to new high-tech materials.”

Barrère, with his powerfully ‘lean and direct’ aesthetic and his embrace of innovative manufacturing processes, is nonetheless driven by an overriding principle: “I love that embroidery can create optical illusions. Like the Kinetic art of the 1960s, hand-sewn designs and motifs can change appearance in different lights. You can create ripples and undulations, like we did on pieces for Chanel’s recent haute couture show [for Fall 2018] inspired by a stroll along the banks of the Seine. Really, you can create anything.” He may have phrased it differently, but Barrère echoes the sentiment of the maison’s original illusionist, Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, who famously said, “Adornment, what a science! Beauty, what a weapon! Modesty, what elegance!”

Alexandra Zagalsky is a London-based journalist specialising in luxury, art and travel. She began her career working on a cultural guide for English-speaking expats in Paris, where her first major break was an interview with Lionel Poilâne, the late baker of Saint-Germain-des-Prés famed for his signature sourdough loaves. Returning to London in her early 20s, she went on to write for not only The Week but also The Art Newspaper’s Art of Luxury supplement, The Telegraph and The Times, as well as art and design platforms including 1stDibs’ Introspective Magazine and the magazines of the V&A, Sotheby’s and Christie’s. She studied fine art and art history at Goldsmiths, University of London and continues to explore travel journalism through the lens of art, craftsmanship and culture.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim RobinsonThe Week Recommends 'Lampooning and embracing' middle-aged male loneliness, this film is 'enjoyable and funny'

-

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptation

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptationThe Week Recommends Dumas's classic 19th-century novel is once again given new life in this 'fast-moving' film

-

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'The Week Recommends The final part of this trilogy deftly explores rising political tensions across the country

-

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'The Week Recommends Colman Domingo plays a real-life prisoner in a performance likely to be an Oscars shoo-in

-

Kaos review: comic retelling of Greek mythology starring Jeff Goldblum

Kaos review: comic retelling of Greek mythology starring Jeff GoldblumThe Week Recommends The new series captures audiences as it 'never takes itself too seriously'

-

Blink Twice review: a 'stylish and savage' black comedy thriller

Blink Twice review: a 'stylish and savage' black comedy thrillerThe Week Recommends Channing Tatum and Naomi Ackie stun in this film on the hedonistic rich directed by Zoë Kravitz

-

Shifters review: 'beautiful' new romantic comedy offers 'bittersweet tenderness'

Shifters review: 'beautiful' new romantic comedy offers 'bittersweet tenderness'The Week Recommends The 'inventive, emotionally astute writing' leaves audiences gripped throughout

-

How to do F1: British Grand Prix 2025

How to do F1: British Grand Prix 2025The Week Recommends One of the biggest events of the motorsports calendar is back and better than ever