Art of the city: the best contemporary art in Kiev

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Snowy streets, iron grey skies, and an ongoing war with Russia: this may not seem like the best time visit Ukraine. But for travellers passionate about contemporary art and culture, Kiev is one of the most fascinating cities in the world today.

Take, for example, artist Lesia Khomenko. Khomenko has projects on show simultaneously in the two largest arts venues in Kiev. At Pinchuk Art Centre, her solo show includes a cardboard model of the artist’s Soviet-era studio building on the recently renamed Perspektyvna street as well as large-scale paintings of anonymous soldiers mounted in specially made wooden frames.

In Kiev, the very fabric of the city has become an ideological battleground, with developers seizing public space and the government tearing down statues and renaming streets under a policy of decommunisation that aims to erase history. In response, Khomenko ponders whether objects such as buildings or picture frames – or even art itself – can bear the meanings we attribute to them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

An interesting comparison is Khomenko contribution to Revolutionize, a lavishly produced exhibition that situates Ukraine’s recent political events within a broader historical and geographical context. The exhibition, curated by Kateryna Filyuk and Nathanja van Dijk, takes place under the high brick vaulting of the state-funded Mystetskyi Arsenal, a vast former arms warehouse built at the end of the eighteenth century.

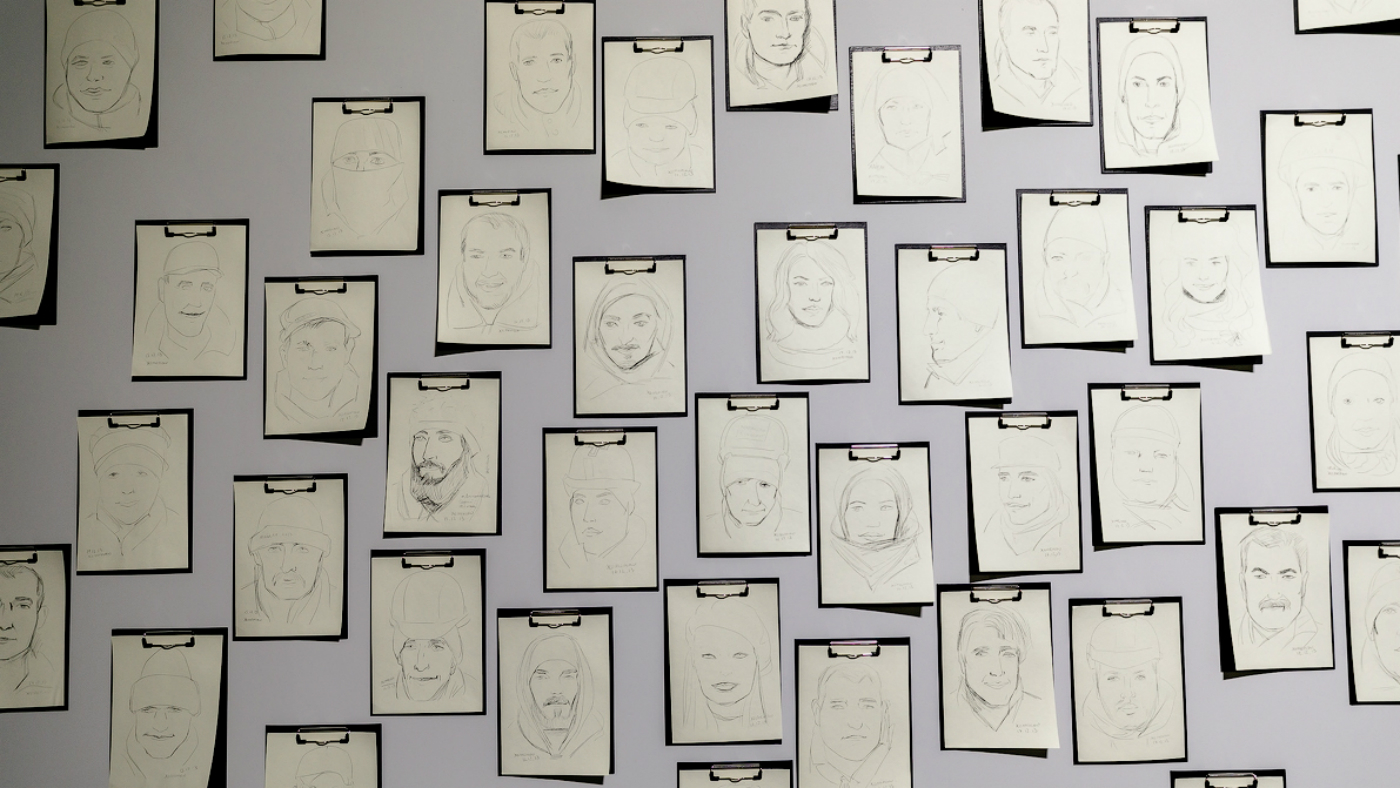

Revolutionize speaks directly to local events and feels close to the ground in its detailed approach to the practice of protest. Alongside contributions from dozens of Ukrainian and international artists, Khomenko presents a series of portraits she made of Maidan protestors. But she gave away the original drawings to those she depicted, so only carbon copies are on show: “the art system,” reads the accompanying text, “can only claim a copy of reality”.

Some Kiev artists who were involved in Maidan feel that Revolutionize focuses too much on objects rather than people, images over ideas. I think the curators are aware of this possibility: a key part of the exhibition is The Revolution of Dignity Museum project to conserve artefacts from the Maidan revolution of 2014. As an outsider, I’m especially struck by the fashioning of consumer goods into protective equipment highlighted in a project by James Beckett: the tiny shin guards that one protestor wore to face the government snipers carry a powerful emotional charge.

It is a good sign for Kiev that neither Pinchuk Art Centre nor Mystetskyi Arsenal are shying away from tackling politics head-on (even if both tread carefully as they do so). Despite the country’s well-documented problems, cultural institutions provide a degree of shelter behind which ideas can be discussed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Pinchuk’s major winter exhibition is Democracy Anew?, which brings together works by art world megastars such as Olafur Eliasson, Damien Hirst, and Takeshi Murakami to comment on the parlous state of democracy today.

Across sculpture, installation, video, painting, and even some extremely delicate biro drawings by Goshka Macuga, the exhibition attempts to deal with feelings of disappointment about the direction that democracy has taken in Ukraine and elsewhere. The inclusion of Zoe Leonard’s famous ‘I Want a President’ poem, recently revisited for the US midterm elections, feels especially provocative in this context: “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with Aids for president,” read the opening lines.

Vital to such exhibitions are the discussions they generate. Democracy Anew? is visually theatrical but can feel emotionally detached. It is the young art students acting as mediators who really bring the exhibition alive. Their passion rubs off on visitors and animated discussions take place throughout the galleries. This is one of the best things about visiting Pinchuk Art Centre: the opportunities that art can provide to discuss complex and important subjects that could otherwise be very difficult to address.

The mediator I speak with most, currently studying for a PhD in philosophy, is especially forthright on the limitations of contemporary art: it makes for hugely refreshing discussions.

At the smaller end of the scale, three very different institutions are doing some of the most important artistic work in Kiev: Visual Culture Research Centre (VCRC), a collaborative curatorial initiative; Soshenko 33, an artist residency space on the outskirts of the city; and Izolyatsia, a gallery, co-working, and residency space. All three have been instrumental not only in providing platforms for contemporary artists in Ukraine but also in facilitating exchanges between Kiev and the international art world.

To visit Izolyatsia, take a short walk from Tarasa Shevchenka Metro station, across overgrown railway tracks, and into an unprepossessing industrial zone on the banks of the river Dnieper. Izolyatsia was located in Donetsk in the east, until Russia’s aggression forced the team to relocate to Kiev and start all over again. Their latest exhibition, We Were Here by Anton Shebetko, highlighted the roles played in the war against Russia by LGBT soldiers in the Ukraine army. By presenting LGBT people in roles that even Ukraine’s far-right must acknowledge as heroic, Shebetko deftly pulled the rug from under the feet of the prejudiced.

And there is more good news for the city’s art scene. Opening this December is The Naked Room, a new space on Reitarska Street which, with its concept stores selling clothing by Ukrainian designers, is rapidly becoming Kiev’s creative hang-out. The gallery has been conceived by Swiss film director Marc Wilkins, who fell in love with Kiev and moved to the city from Berlin in 2017.

With curators Lizaveta German and Maria Lanko overseeing the programming, the gallery will showcase the work of what they describe as “the artists of our generation”. The opening exhibition sets the tone with photographic tales from Ukrainian suburbia by Olena Subach and Viacheslav Poliakov. The Naked Room also plays host to a library and bar-restaurant.

At the state level, things are moving too. 2017-18 saw the launch of two new cultural funding programmes: the Ukrainian Institute, which will represent Ukrainian culture abroad, and the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, established in order to “facilitate development of culture and arts in Ukraine”. It is early days for both, but the mere fact that they now exist suggests Ukraine’s government increasingly recognises the importance of art and culture.

In the absence of long-term public funding for the arts, Pinchuk Art Centre has been a vital focal point since it was founded in 2006. Spread across six floors, the gallery is funded by Ukrainian billionaire businessman Victor Pinchuk. Under artistic director Björn Geldhof there has been a consistent focus on big-name international artists like Marina Abramović, Anish Kapoor and Ai Weiwei alongside a championing of the artists of Ukraine.

Pinchuk Art Centre’s other big initiatives have been annual prizes for artists under the age of 35: the Future Generation Art Prize for international artists and the Pinchuk Art Prize for artists from Ukraine. Both seek to generate discussion between Ukraine and the wider art world. This diverse programme provides a significant draw for Kiev’s art-hungry audiences. Every day the galleries are humming with young people discussing the works on show. Entry to Pinchuk Art Centre is completely free and around 1,500 people visit every day.

But arguably Pinchuk Art Centre’s most important work is what goes on behind the scenes. For the past two and a half years, the centre has employed a twelve-strong team of researchers to build a more accurate picture of recent Ukrainian art history. During the Soviet era the most interesting art was being produced outside of official channels. Documentation, if it still exists, can be hard to find. So by bringing together, organising and digitising the personal archives of many important artists, Pinchuk Art Centre is helping a new generation to get a clearer sense of Ukraine’s art historical legacy.

This research also leads directly into the public programming, which is good news for visitors to Kiev. On show right now is A Space of One’s Own, a group show that celebrates the vital and frequently overlooked work of Ukrainian women artists from 1980 right up to the present day. Highlights include paintings with embroidery by Maryna Skugareva and a series of dress-like sculptures made by Zhanna Kadyrova from the tiles of now demolished Soviet-era buildings.

In a political context that can feel overwhelming in its complexity, such exhibitions demonstrate that art has a vital role to play in discussions over Ukraine’s past, present and possible futures.

Where to stay in Kiev

Bursa is a brand-new 33-bedroom boutique hotel housed across two early 19th century buildings in historic Podil. With café, art gallery, shop, library and rooftop bar, this is theplace to mingle with the city’s young artists and designers. For those after a slice of the oligarch lifestyle, Premier Palace is a feast of reproduction nineteenth-century paintings and lashings of gilt and wood veneer, but the service is great and the breakfasts stupendous.

Where to eat

The legendary Yaroslava café is a must-visit: its interiors – like a Soviet interpretation of National Romanticism – as extraordinary as the array of home-baked sweet and savoury buns. Those in search of something more contemporary should check out vegetarian cafe Orang + Utan, The Cake, a pastry specialist with a love of Jeff Koons, or all-white top-floor café at Pinchuk Art Centre. For brunch, go to Zigzag on Reitarska Street and try the savoury oatmeal or sweet dumplings swimming in berries and home-made yoghurt.

The best coffee in town is at Kashtan, also on Reitarska Street, or Blur. Come evening, JZL is a lively hangout with Middle Eastern tinges (halloumi salads and grilled shrimp pitas) while Kanapa does an upmarket take on traditional Ukrainian cuisine.

After dark

Kiev has long been famous for its clubbing scene and the centre of it all is Closer. This is the place to go for gigs and parties that will last long into the next day. But Closer is not just a night-time escape valve for Kiev’s beautiful youth; the club also plays host to calm concerts, discussion events, and an excellent programme of exhibitions in its dedicated gallery space. There’s a snazzy new restaurant too.

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Eurovision faces its Waterloo over Israel boycotts

Eurovision faces its Waterloo over Israel boycottsTalking Point Five major broadcasters have threatened to pull out of next year’s contest over Israel’s participation

-

How global conflicts are reshaping flight paths

How global conflicts are reshaping flight pathsUnder the Radar Airlines are having to take longer and convoluted routes to avoid conflict zones

-

Sarah Rainsford shares the best books to explain Vladimir Putin's Russia

Sarah Rainsford shares the best books to explain Vladimir Putin's RussiaThe Week Recommends The correspondent picks works by Anna Politkovskaya, Catherine Belton and more

-

The Zelensky Story: as 'astonishing as it is inspirational'

The Zelensky Story: as 'astonishing as it is inspirational'The Week Recommends BBC Two's three-part documentary features 'genuinely revealing' interviews with the Ukrainian president

-

War tours: how tourism in Ukraine is bouncing back

War tours: how tourism in Ukraine is bouncing backUnder the Radar Visitors are returning to the war-torn country but not everyone is happy to see them

-

Eurovision 2024: how is politics playing out in Sweden?

Eurovision 2024: how is politics playing out in Sweden?Today's big question World's most popular song contest 'has always been politically charged' but 'this year perhaps more so than ever'

-

Elizabeth Gilbert and the debate over cancelling Russian culture

Elizabeth Gilbert and the debate over cancelling Russian cultureTalking Point Decision to delay publication of novel set in 20th-century Siberia sparks intense debate

-

The weirdest Eurovision performances of all time

The weirdest Eurovision performances of all timeIn Depth All the weird – and wonderful – acts that have left Eurovision audiences stunned, from Windows95man to Dustin the Turkey