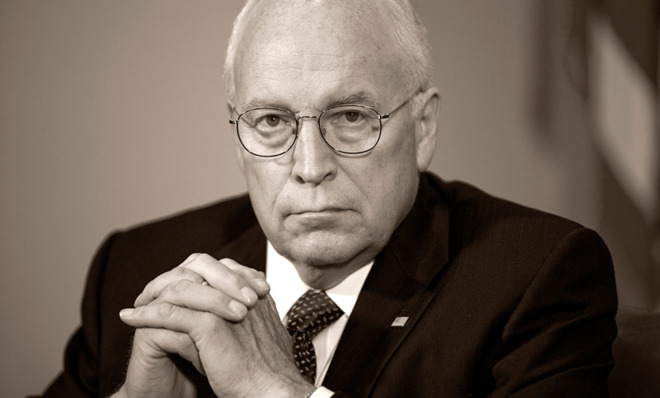

Dick Cheney's America is an ugly place

This is what will happen if the ends are allowed to justify any means — including torture

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I used to like Dick Cheney.

I can still remember watching him on NBC's Meet the Press back in the early 1990s, when he was serving as defense secretary under President George H. W. Bush. Whether he was talking about the collapse of the Soviet Union or making the case for expelling Saddam Hussein's army from Kuwait, Cheney was impressive. Unlike so many career politicians and Washington bureaucrats, he came off as charming, sober, smart, unflappable, and sincere.

Today? Well, I'll give him this: He still seems sincere.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some day I hope some psychologically gifted writer will turn his attention to Dick Cheney and explore just what the hell happened to him after the Sept. 11 attacks. Something about the trauma of that day — perhaps it was the act of being physically carried by the Secret Service into the Presidential Emergency Operations Center under the White House — flipped a switch in his mind, turning him into America's foremost champion of amoral patriotism.

The man interviewed on Meet the Press this past Sunday resides completely beyond good and evil. Despite the manifest failure of the CIA's "enhanced interrogation techniques" to generate actionable intelligence, he has no regrets whatsoever. ("I'd do it again in a minute.") He expresses nothing but contempt for the Senate intelligence committee's 6,000-page report, based on 6 million pages of documents, meticulously cataloging forms of treatment that virtually every legal authority in the world and every totalitarian government in history would recognize as torture. Waterboarding, "rectal feeding," confining a prisoner in a box for a week and a half, dangling others by their arms from an overhead bar for 22 hours at a time, making prisoners stand on broken bones, freezing prisoners nearly to death — none of it, according to Cheney, amounts to torture.

What does constitute torture? For Cheney, it's "what 19 guys armed with airline tickets and box cutters did to 3,000 Americans on 9/11." (Maybe our military response to the events of that day should have been christened "The Global War on Torture.")

Perhaps most stunning of all was Cheney's response to Chuck Todd's question about 26 people who, according to the Senate report, were "wrongfully detained" by the CIA at its overseas black sites. The imprisonment and torture of innocent people? "I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective." The end justifies any means. Got it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Cheney's hardly the first person to defend such a position. Machiavelli advocated a version of it in The Prince. It's been favored by some of the most ruthless nationalists and totalitarians in modern history. And it's expressed in Book 1 of Plato's Republic by the character Polemarchus (the name means "leader in battle"), who defines justice as helping friends (fellow citizens) and harming enemies (anyone who poses a threat to the political community). This is what patriotism looks like when it's cut off from any notion of a higher morality that could limit or rein it in. All that counts is whether an action benefits the political community. Other considerations, moral and otherwise, are irrelevant.

The problem with this view, which Socrates soon gets Polemarchus to see, is that amoral patriotism is indistinguishable from collective selfishness. It turns the political community into a gang of robbers, a crime syndicate like the Mafia, that seeks to advance its own interests while screwing over everyone else. If such behavior is wrong for an individual criminal, then it must also be wrong for a collective.

But this judgment presumes the existence of a standard of right and wrong that transcends the political community. Just as an individual act of criminality is wrong because it violates the community's laws, so certain political acts appear worthy of being condemned because they seem to violate an idea of the good that overrides the politically based distinction between friends and enemies.

There are many such standards. In the Republic, Plato's Socrates nudges Polemarchus toward the view that true justice is helping friends who are good and harming no one. Then there are the Hebrew Bible's commandments and other divine laws, Jesus Christ's insistence on loving one's enemies, categorical moral imperatives, and the modern appeal to human dignity and rights — all of these universal ideals serve to expand our moral horizons beyond the narrow confines of a particular political community and restrict what can be legitimately done to defend it against internal and external threats.

Against these efforts to place moral limits on politics stand those, like the former vice president, who claim that public safety depends upon decoupling political life from all such restrictions. Friends and enemies, us and them, with us or against us, my country right or wrong — it doesn't matter which dichotomous terms are used. All of them emphasize an unbridgeable moral gulf separating the political community from those who would do it harm. And that gulf permits just about anything. Even torture. Even the torture of innocents. Even redefining torture out of existence in order to exonerate the perpetrators. Everything goes, as long as friends are helped and enemies are harmed.

That's what Dick Cheney — along with a distressingly large number of Americans — understands by patriotism: a willingness to do just about anything to advance the interests of the United States and decimate its enemies.

Just like a lawless individual.

Just like a gang of robbers.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spot

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spotThe Week Recommends The trendy hotel recently underwent an extensive two-year revamp

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred