Why linguists freak out about 'absofreakinglutely'

They don't even really know what to call it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fan-freaking-tastic!

What?

Ling-freaking-guistics, that's what!

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Too damn right.

Want to get a bunch of linguists on a problem lickety-frickin'-split? Just drop something naughty in the middle of a word or phrase. Like fan-freaking-tastic or too damn right or Judas H. Priest.

The exact linguistic analysis of something like abso-freaking-lutely has gotten quite a few linguists pretty exercised over the years. They don't all agree.

So let's talk about what it's not.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's not new.

Let's start with this one: the insertion of emphatic words, usually rude, in the middle of other words or fixed phrases is not something that came about in the last few decades. H.L. Goshdarn Mencken was writing about it in 1936. One of the classic papers about it, by James Bleeping McMillan in 1980, gives an example from 18-fricken-46: "Theojollylogical." (You have to wait until the early 1900s before people started stuffing actual rude words into other words in print.)

It's not random.

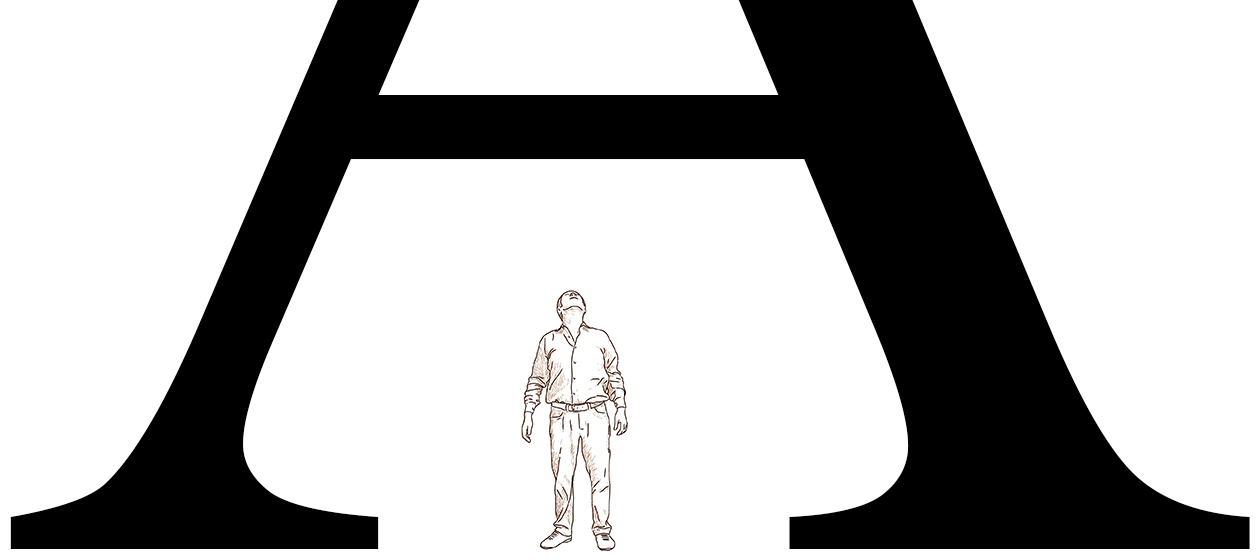

When you insert a word for emphasis — be it fricking, bleeping, something ruder, or something less rude — you can't just stick it any old where. We know this because abso-freaking-lutely is fine but ab-freaking-solutely or absolute-freaking-ly is not. Whether it's in a word, a phrase, or a name — you stick the emphatic addition right before a stressed syllable, usually the syllable with the strongest stress, and most often the last stressed syllable. What we're doing, in prosodic terms, is inserting a foot.

A foot, in this case, is a unit of rhythmic measurement consisting of a stressed syllable and zero, one, or sometimes two (or maybe even three) unstressed syllables. If you've learned about poetry, you know that there's a difference between, for instance, a trochee — a two-syllable foot that has the stress first, as in "liver" — and an iamb — which has the stress last, as in "pâté."

When it comes to sticking these extra feet in, we normally break the word or phrase according to the rhythm of what we're inserting. "To be or not to be, that is the question" is thought of as iambic pentameter, but you won't break it between iambs if your interrupting foot is a trochee: "To be or not to bleeping be," not "To be or not bleeping to be"… But if it's an iamb? "To be or not the heck to be," not "To be or not to the heck be."

Look, these are rude, interrupting words. They're breaking in and wrecking the structure. That's the freaking point. But they still do it with a rhythmic feeling.

It's not meaningless.

Some linguists have analyzed it as just an insertion of an expletive intensifier, with no literal meaning. Jennifer Freaking Lawrence is not literally freaking; abso-bloody-lutely true is absolutely true but not bloody.

But we can also use words this way for their actual meanings. Zero-dark-thirty gets meaning from dark. San Fran-foggy-cisco definitely has an added sense to it. And Michael Adams, in his paper "Infixing and Interposing in English: A New Direction," gives this great example from the movie Heathers: "US-f—ing-A Today" (well, he prints the actual vulgarity), which uses an emphatic vulgarity but plays on the phrase f—in'-A.

See, we're breaking things for effect. There's a way we do it — the rhythm matters — but we can bring in as many different references and levels of meaning as we want and can handle.

It's not an infix.

Very often, linguists will call these inserted words infixes. What's an infix? It's like a prefix (like un– in unbroken) or a suffix (like –ing in breaking), but instead of going at the beginning or the end of a word, it goes in the middle. Some languages have them. English does not. Some linguists say that cases like abso-freaking-lutely are an exception. But I say they're not.

I know that when I say they're not, I'm going against James Bleeping McMillan, who wrote the classic paper "Infixing and Interposing in English," and John Jumpin'-Jiminy McCarthy, who wrote the other classic paper "Prosodic Structure and Expletive Infixation." But I'm going — at least for the most part — with Arnold Mofo Zwicky and Geoffrey Freaking Pullum, who wrote a slightly more recent and also classic paper, "Plain Morphology and Expressive Morphology."

First, as Zwicky and Pullum explain, affixes (which include prefixes, suffixes, and infixes) apply to specific classes of words:–ed and –ing are added to verbs, un– to adjectives or verbs, anti– to adjectives or nouns. Our inserted feet as in abso-freaking-lutely can go into any kind of word.

Second, affixes have to be put at morpheme boundaries. A morpheme is the smallest meaning-carrying unit; a word like amen has only one morpheme. But McMillan gives an example of people saying "a-damn-men," sticking the rude word right in the middle. It's just the rhythm that matters. And the rudeness.

Third, affixes have specific, clear rules, but there is some vagueness and flexibility with our inserted feet: inter-freaking-continental or interconti-freaking-nental, for instance.

To these observations I'll add, as has been pointed out by various people, that these are whole words, capable of standing alone, which is generally not the case with affixes: pre, anti, un, and ed are not words.

And this foot insertion doesn't just happen in individual words. McMillan's paper is about "infixing and interposition" because the interposition part is about doing the same thing in set phrases, such as all of a bleeding sudden and too damn right, and in names, such as New Frickin' York and Tony Frickin' Bennett. (Here's one for you: Where would you stick it in Frank Sinatra?)

This matches a grammatical pattern we've set elsewhere. For example, we put adjectives before nouns, and adverbs before verbs. We're used to inserting things right before the key point. You can hear what that does to the rhythm of the speech: "Do you want it? Do you really want it? Do you really, truly want it?" We add extra punches of increasing intensity right before the key stressed word (want, in this case). We can add a whole nother word to just about any old thing.

So what is it?

So really, this foot insertion is a kind of playing with language. That's what Zwicky and Pullum say, and I agree. It's a bit of expressive morphology that makes use of an existing pattern: add another punch to build up right before the big punch.

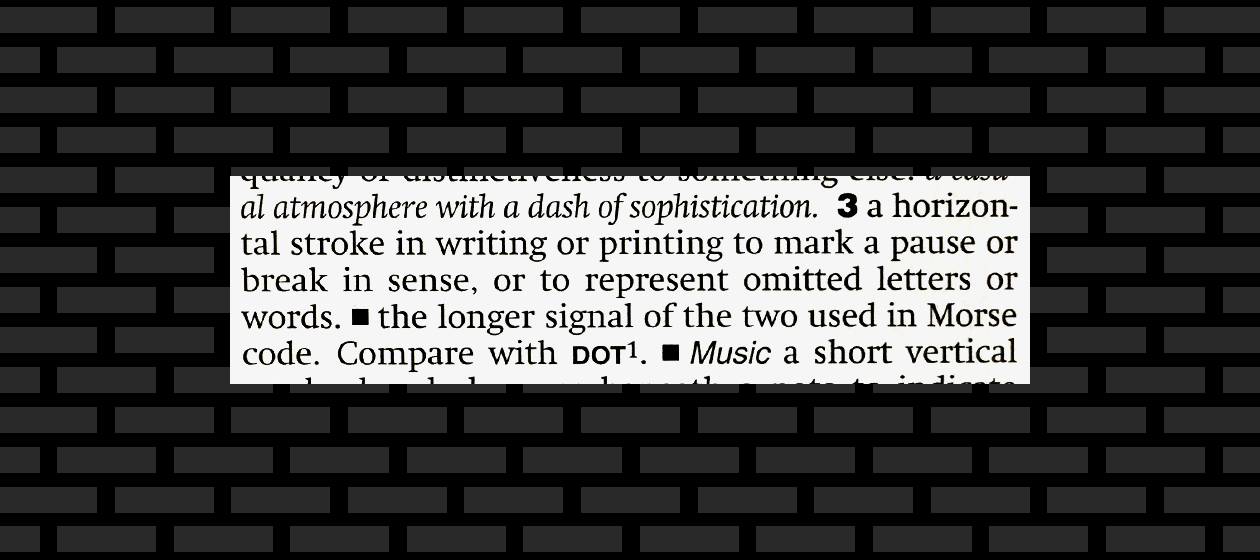

So what shall we call it? Some call it infixing or expletive infixation, but it's not a real infix. There's another term, tmesis, which could maybe work, but linguists disagree on the definition of tmesis, and many people aren't sure how to pronounce it. It's rhythmically determined, so I've been calling it foot insertion, but that's kind of dull, isn't it? What's another way of saying 'putting a foot in?'

Hmm. How about inkicking? Yes, I really freaking like that. Abso-goshdarn-lutely.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.