The enduring traumas of September 11

A look back at lessons not learned

September 11, 2001, began just like every weekday morning. Fifteen years ago today, I boarded a Metro-North commuter train in suburban Fairfield, Connecticut, at 7:09 am. Arriving at Grand Central Terminal in midtown Manhattan 80 minutes later, I transferred to a downtown 6 train and emerged from the subway at the corner of East 23rd Street and Park Avenue South. I walked for a block and turned right on 22nd Street in the direction of 5th Avenue. Just like every weekday morning.

Somewhere on my crosstown stroll to the offices of First Things magazine, I heard a deafening roar come out of nowhere and glanced upward just in time to see a passenger jet scream by heading south, flying far too fast and far too low. It was alarming. But only for a second. This was, after all, "before September 11," when terrorism was something that happened in other places — and certainly not on the scale I would behold over the next few hours.

I was born in New York City and raised in and near it. My earliest memories of the skyline included the Twin Towers. They were always there when I pictured the city in my mind's eye, just as they were always there when I turned downtown at 5th Avenue on my way to my office on 20th Street. But this time there was a huge horizontal gash high in the facade of the right-hand tower — and an immense dissipating cloud of smoke floating away in the blue sky above it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I called my wife to tell her to turn on CNN for news of the ghastly, freak accident I'd nearly witnessed. And then I ran as fast as I could to work.

September 11 became "September 11" a few minutes later, when the second plane banked sharply over New York Harbor and rammed into the other tower with unmistakable intentionality, eliciting shrieks of horror from bystanders gathered on the street outside our offices and clarifying the reality of what we were witnessing. This wasn't the Hindenburg. It was Pearl Harbor.

We were under attack.

The next few hours were a hazy blur of confusion and panic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Try to call wife again; cell service down. Return to street and gaze in shock at the apocalyptic scene unfolding two miles away. Call father, at work half a mile uptown, who reminds me that my younger brother is attending a conference on Wall Street that morning, just three blocks from the second stricken tower. Try to ease father's mind. Pentagon burning, says a colleague. My God, what's happening? More and louder screaming from the street, frantic fiddling with an old, barely functional TV set in boss' office to get news. "Tower gone." What? How is that possible? "Reports of car bombs near the State Department." Call father again; talk of burying youngest son later that week. "Second tower gone." This can't be happening. Return to street to gape at what looks like a massive erupting volcano spewing impossibly wide plume of orange-brown-gray smoke into the sky where the towers used to stand.

It could have been worse. At least for me.

My brother showed up at my office two hours later, stunned. He'd watched both towers collapse as he made his way up the FDR Drive, transformed by events into an evacuation route for pedestrians. We even met up with my father for a long, dazed lunch at a midtown bar that afternoon, as TVs replayed footage from that morning on a continuous loop. Two hours later, we made it onto the first Metro-North train to leave Grand Central since 9 a.m. It crawled and made every stop on the way out to Connecticut, but I got home by 7 p.m. — just like every other evening.

Except that this time I broke down sobbing as soon as I made it through the front door.

The next several months are as much of a blur as the events of that traumatizing day. Military jets constantly circling overhead. Posters of the missing plastered on every lamppost and empty wall in Manhattan. Buying the first American flag I've ever owned and flying it defiantly outside my home. Anthrax attacks arriving by mail at offices in New York and Washington. Walking to my train in the evening past soldiers armed with machine guns, imagining the scene if a suicide bomber detonated himself as I scrambled (faster than I used to) across the concourse. Shivering at articles laying out the possibility of a nuke being smuggled into Manhattan in an unmarked white van — and pondering the catastrophic personal and civilizational consequences of its detonation blocks away from my office.

Those were deranging times. I was so fearful in those days that I actually expressed regret to a friend that the fourth plane had failed to destroy the White House. The thing I feared most in those initial weeks after the attacks, you see, was that we would hesitate in striking back against our enemies. I wanted assurance of our national resolve, and I thought that nothing short of a vision of the White House in ruins would guarantee it.

I'm not proud that I had such thoughts and fears. But I wasn't the only one. Some members of the Bush administration obviously had them, too. Those thoughts and fears convinced them that the United States needed not only to depose the Taliban in Afghanistan, capture or kill Osama bin Laden, and destroy al Qaeda, but to start a second war, in Iraq, to remove the supposedly intolerable threat posed by Saddam Hussein. It was a bizarre, world-historical case of overreaction, as all but a handful of countries understood at the time.

How did they know?

Because they knew history — their own and ours.

New York City was dreadful that day. To be the target of a sneak attack. To see loaded passenger jets turned into guided missiles. To witness two massive skyscrapers collapse into a smoking, twisted pile of debris, the thousands of people trapped inside pulverized into dust. A horror.

But what of history's other horrors — horrors on a scale that make September 11 look like child's play?

The Red Army lost more soldiers (just soldiers) in the Battle of Stalingrad than the number of people the United States has lost (both soldiers and civilians) in every war in American history combined. In the nearly century and a half since the conclusion of the Civil War, Americans have had no firsthand experience of war on their own soil — and no experience of foreign occupation since the War of 1812. And unlike the citizens of London, Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, they have no experience of aerial bombardment leveling whole neighborhoods of cities and leaving behind blocks of rubble and countless thousands of charred, mutilated corpses.

Aside from that one morning 15 years ago.

This is a very good thing, of course. Americans should be very grateful to have been spared so much of the immense suffering wrought by modern warfare.

But our absence of experience also makes us far too sanguine about the efficacy and moral legitimacy of using military force. Neocon (and Hillary Clinton adviser) Robert Kagan may seriously believe that America has a "dangerous aversion to conflict." I think the historical record shows quite the opposite — that the United States finds it nearly impossible to go more than a few months at a time without blowing other people to bits, sometimes face to face, more often from a conveniently safe distance.

Americans understandably like their homeland insulated from the rest of the world's conflicts — and they're prone to act impetuously in a sometimes desperate and slightly paranoid effort to keep it that way. Fine. But please, let's be honest about the human and geopolitical consequences. A decade and a half later, we're still desperately working to clean up the mess created in large part by our wildly excessive response to a single morning of murder in lower Manhattan.

Although I never supported the Iraq War, I understand how smart, well-meaning people were able to convince themselves it was an absolutely necessary response to a dire threat. I spent several months 15 years ago stuck in that state of mind.

But then I got over my trauma and came to my senses.

I'm still waiting for more of my fellow citizens to do the same.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on September 11, 2014. It was slightly updated on September 11, 2016.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

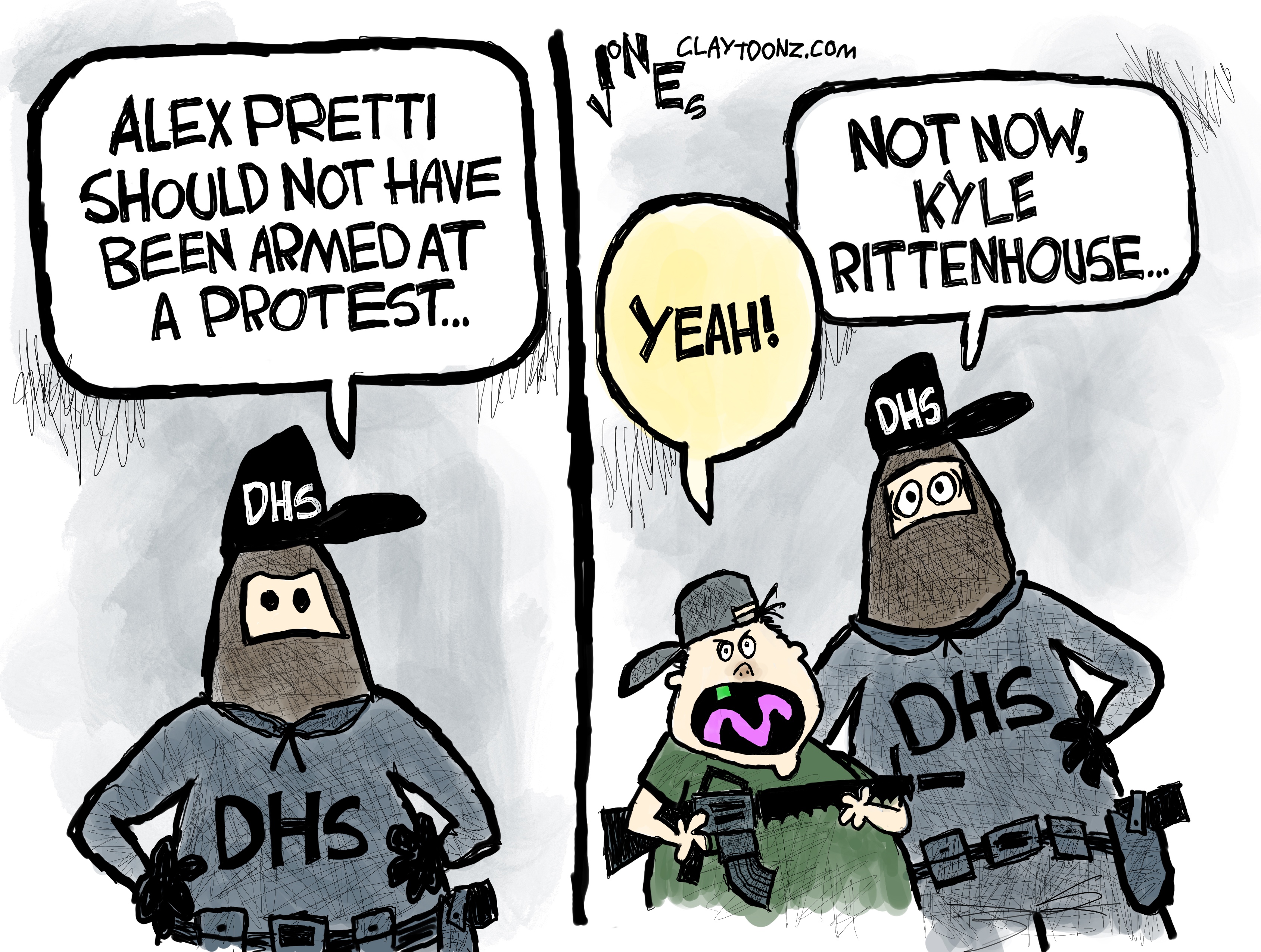

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred