How conservatives learned to hate Hollywood

American movie studios are no longer making movies specifically for Americans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The 1970s — a time of cultural malaise, androgynous fashion mistakes, and street crime. A lot of subversive but critically acclaimed movies from this era (from Annie Hall to M*A*S*H) reflected America's somewhat disaffected zeitgeist. But beneath the surface, a new genre of patriotic action hero was emerging.

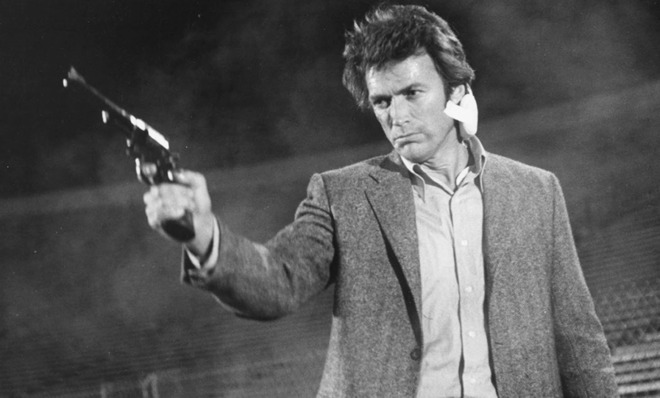

Charles Bronson turned vigilante in Death Wish, a film that spoke to the crime problem endemic in big cities like New York. And Clint Eastwood as Inspector Harry Callahan (aka "Dirty Harry") took on criminals and the bleeding-heart liberals whose "technicalities" prevented him from taking murderers and rapists off the streets.

It began as a trickle, but these films were a sort of release valve, allowing ordinary conservative Americans — folks who might never attend a political rally, but still sensed something was wrong as they lost control of the culture — to make a political statement just by buying a ticket.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It must have scratched an itch, because the decade that followed would give birth to a second-wave of action heroes who were even more muscular and more conservative-friendly — men like Sylvester Stallone, who, when he wasn't duking it out with Ivan Drago in the boxing ring, spent the better part of a decade fighting his own surrogate cold war against the Soviet Union in the Rambo movies. Stallone dominated the box office, and along the way, helped exorcise the Vietnam syndrome's defeatist demons.

Now, none of this is to say that these movies were obviously and intentionally "conservative" in the conventional sense of the word. Russell Kirk would probably not find much to recommend them. Indeed, these movies are not even conservative in the sense that Patton was a conservative film.

Instead, this was a new genre of action films that appealed to conservatives. These movies and their stars weren't as wholesome as John Wayne, but they still tapped into an underserved market of patriotic Americans who felt the nation was adrift or still imperiled by the Cold War — and that liberal Hollywood was ignoring them.

Grantland's Wesley Morris said it well in a recent BS Report podcast:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When Eastwood and Stallone and Schwarzenegger were stars, they were starring in movies made by American directors who had something to say about the country. They sensed something was off... The country was sliding off the rails. The moral balance had gotten out of whack. There was a real sense that the country was going crazy, and that whatever was going crazy in it had to be stopped. [BS Report]

You can see how that might appeal to conservative filmgoers!

These films were about fighting back and standing up for American values — something that liberals were seen as being too wimpy or too sophisticated to do. It's also important to note that one of Ronald Reagan's primary objectives was to restore a sort of swagger back into the American psyche. In many ways, this drove his foreign policy objectives, including a hasty withdrawal from Lebanon after the Beirut barracks bombing.

Indeed, this genre of movie seemed to work in tandem with the Reagan administration's efforts to move past the bad old days, and move forward to a new "win" psychology. The Rambo-Reagan connection did not wholly escape we conservatives at the time. I am both proud and a little embarrassed to admit that I owned a "Ronbo poster." (Yes, such things existed.)

So what's wrong with Hollywood today — and how did conservatives learn to hate Hollywood?

The obvious reason is Hollywood doesn't make movies like it used to. The conservative-friendly action heroes are mostly gone.

But another is that a lot of today's CGI-heavy action films seem, well, liberal. Iron Man is basically rebelling from his work building arms for the U.S. The Incredible Hulk is a military experiment gone wrong. X-Men are all victims of discrimination. And so on.

Here's another problem: Hollywood is no longer creating films specifically for Americans. The global box office is increasingly crucial for a big-budget movie's success. When they're crafted to appeal to Chinese and Russian audiences, films no longer scratch that unique conservative American itch. When we watch movies tailored to the world, we lose a sort of cultural connection.

It is, perhaps, easiest to illustrate this point by comparing apples to apples — by looking at how Hollywood handles remakes from that era instead of comparing 1980s era movies with today's original works.

Consider the 2012 remake of the 1984 classic Red Dawn. The original was about the Soviet Union's invasion of a small town in Colorado. The remake failed to recapture the magic. Come 2012, there was no Soviet Union. China might have made sense, but the film's creators decided that casting the Chinese as the villains might hurt international sales. And so, they decided to make North Korea the bad guys. Suffice it to say, the end result failed to inspire future conservatives the way the original did.

"We're not telling a story about America now, because these movies are trying to play to China and Japan and Germany and Russia and Indonesia," Morris said. "You now are trying to serve a global audience. And I think that's been the shift."

Of course, it's not just conservatives who should be concerned by the shift. Could a film like The China Syndrome get made today — or would it offend nations like France who value nuclear energy?

Why does any of this matter? Because if there is any industry whose exports have larger effects than those of Hollywood, I don't know what it is. What is the role of entertainment? Is it an opiate, or a temporary escape, or a means of enlightenment? It is all of these things, yes. But it also used to be something that engaged and inspired us. That is becoming less and less true today.

The old line about "bread and circuses" (or, as one of my old college professors put it, "pizza and football") implies that wise governments supply trivial diversions to appease the masses. Filling our heads and bellies with empty, if titillating, calories placates us. This, the Romans figured, was superior to having us ask too many questions about politics.

This is cynical, of course. The most actively-engaged citizens sometimes need a break, too. During World War II, for example, when the question arose as to whether to continue playing baseball, FDR advised baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis: "[I]t would be best for the country to keep baseball going," noting that it would provide American workers a "chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before."

Around the same time, the theater served a similar function, allowing Americans a chance to escape reality, engage in fantasy, and blow off some steam. Like baseball, Hollywood was a uniquely American invention, with films created by Americans, for Americans, serving to entertain Americans. But unlike baseball, movies had the added benefit of sometimes helping Americans confront important questions they couldn't address in the real world.

And this is something that I fear is lost to history.

Matt K. Lewis is a contributing editor at TheWeek.com and a senior contributor for The Daily Caller. He has written for outlets including GQ Politics, The Guardian, and Politico, and has been cited or quoted by outlets including New York Magazine, the Washington Post, and The New York Times. Matt co-hosts The DMZ on Bloggingheads.TV, and also hosts his own podcast. In 2011, Business Insider listed him as one of the 50 "Pundits You Need To Pay Attention To Between Now And The Election." And in 2012, the American Conservative Union honored Matt as their CPAC "Blogger of the Year." He currently lives in Alexandria, Va.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred