LBJ's 'War on Poverty' and the perils of inflated political rhetoric

Setting a low bar has its benefits

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

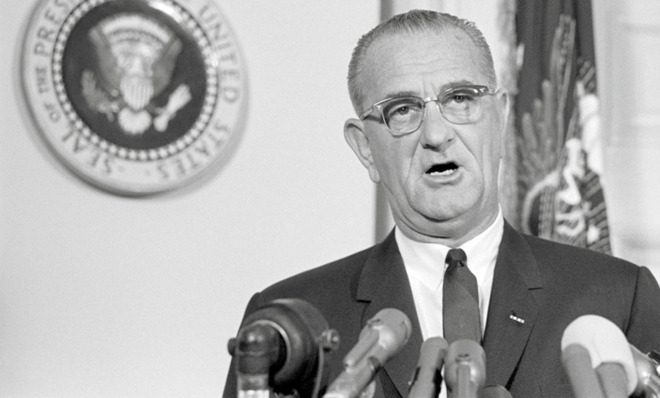

Fifty years ago this week, Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty. Though some are tempted to look back with nostalgia on that rallying cry and the resulting Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 — and even to treat it as a blueprint for a populist Democratic president of the future — Johnson’s decision to propose a rhetorical declaration of war deserves to be treated as a cautionary tale.

The powers of the presidency are remarkably lopsided. In foreign policy, the president is the commander-in-chief in charge of the most powerful military in the world and rarely challenged by Congress when he chooses to send those forces into battle. Since the start of the war on terror, these powers have expanded still further, to include the authorization of torture for terrorism suspects, widespread domestic surveillance, and even the selective murder of American citizens without trial.

But in domestic policy, the president’s powers can seem absurdly modest. The president can propose legislation, but it’s up to the legislature to enact it. Besides backroom arm-twisting, the only way a president can influence that process is to go over the heads of Congress to seek popular support for his legislative agenda. And the most effective method of doing that is deploying rhetoric in public speeches.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That’s why LBJ — himself no slouch at arm-twisting — picked up the rhetoric of a “war on poverty” from John F. Kennedy’s 1960 campaign and attached it to his administration in the wake of JFK’s assassination. What better way for Johnson to bring his influence in domestic policy into line with his much greater power to make foreign policy than transforming his domestic agenda into the rhetorical equivalent of war?

Judged in the narrowest political terms, Johnson’s act of rhetorical inflation worked: The legislation passed. But the victory came at a cost. For one thing, Johnson chose to label his anti-poverty efforts a “war” before his administration had very many concrete policy proposals to offer. Which is a lot like authorizing an actual war prior to giving a single thought to a strategy for victory.

Johnson wanted, above all, to signal urgency, and then he assumed policies would be devised to achieve the goal, which was “not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty, but to cure it.” Needless to say, this isn’t the way to ensure the best policies get enacted, and it may have led to a bill packed with a grab bag of programs that fell far short of achieving Johnson’s wildly ambitious aims.

And that points to an even more troubling consequence of Johnson’s declaration of metaphorical war. Wars are normally declared when the nation faces a major threat to its well-being and even survival. The stakes are enormous — justifying potentially monumental sacrifices, including loss of life — all for the sake of a victory presumed to be absolutely essential to the national interest.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Democrats and Republicans can bicker about how much good the War on Poverty accomplished. But it obviously didn’t “cure” poverty, which means that, judged by Johnson’s own standards, the war ended in defeat — a rhetorical inversion that Ronald Reagan eagerly pounced on. And as Johnson’s presidential successors learned as they attempted to conduct the nation’s foreign policy in the wake of Johnson’s other major defeat, nothing breeds disillusionment and cynicism like failure. That’s why Democrats looking to place the blame for the turn away from activist government in subsequent decades could do worse than reflecting on Johnson’s decision to raise the rhetorical stakes so high.

Which isn’t to say that Democratic presidents are the only ones guilty of rhetorical overkill. It was George W. Bush, after all, who in his second inaugural address foolishly proclaimed the impossible goal of “ending tyranny in our world.” Presidents of both parties would be wise to resist the urge to inflate their rhetoric — just as citizens would be wise not to reward it.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred