This may be why youngest children are so bratty

A new study helps explain why some parents baby their youngest children way past babyhood

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

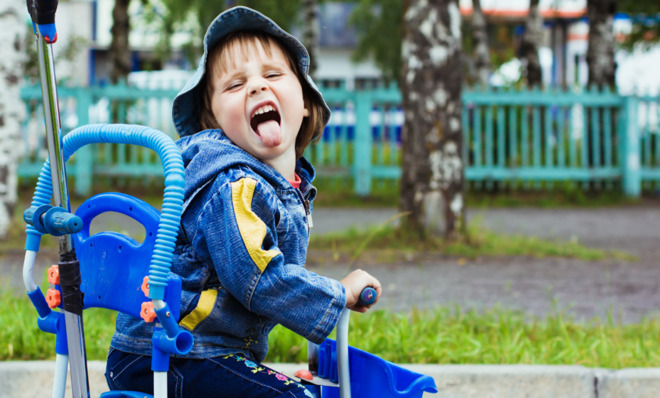

It's a popular opinion that youngest children are often less resourceful and more bratty than their older siblings. Parents tend to treat their youngest children like babies for years, say the haters, which can shape them into less capable, more entitled adults.

Though the science of youngest-child-syndrome is very much up for debate, new research from Jordy Kaufman, a senior research fellow at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, might help explain why some parents baby their youngest children long past babyhood.

In a survey of 747 mothers, 70 percent recalled that when returning from the hospital with a newborn, their former youngest child seemed noticeably larger than they remembered.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But rather than suddenly overestimating the size of their older children, Kaufman believes the mothers may have been suffering from the "baby illusion," where they underestimate the size of their newborns. Asking 77 mothers to estimate the height of one of their children between two and six years old, he found the moms consistently guessed low for their youngest child, or only child, by an average of three inches. Meanwhile, they guessed their oldest child's height pretty accurately.

Kaufman says the baby illusion may have developed as an adaptive mechanism to protect the most vulnerable offspring. "A perception of baby-like features, such as cuteness or smaller size, helps parents prioritize care for the child who most needs it," says Joy Jernigan at Today.

This may play into a mother's desire to baby her youngest for years, while treating her oldest children like "big kids," even if they're only two or three. "Our research potentially explains why the 'baby of the family' never outgrows that label. To the parents, the baby of the family may always be 'the baby'," Kaufman told the BBC.

All this seems to fit nicely into the "birth order theory," a kind of controversial idea that says the sequence of births impacts how smart, outgoing, and successful people become as adults. Though researchers point out that this is a nearly impossible theory to test — how does one control for variables like socioeconomic status, sex, parental birth order, and other environmental circumstances, for example — hundreds of studies have identified certain characteristics that only oldest, middle, and youngest children tend to share with their kind.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Here's how Susan Krauss Whitbourne, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, describes the profile of the youngest-borns in Psychology Today:

The youngest child may feel less capable and experienced, and perhaps is a bit pampered by parents and even older sibs. As a result, the youngest may develop social skills that will get other people to do things for them, thus contributing to their image as charming and popular. [Psychology Today]

Burn. Older children, who may suddenly look big to their moms when a new baby comes home, may not grow up as charming and popular as the little ones. But, according to the birth order theory, they tend to come out on top in other ways. A 2010 study that compiled data from 200 birth order trials found that first-borns tended to be higher achievers, more motivated, and more successful in academic and intellectual pursuits.

Carmel Lobello is the business editor at TheWeek.com. Previously, she was an editor at DeathandTaxesMag.com.