Kill the apostrophe!

We would all be better off without it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The English language would be better off without apostrophes.

Yes, I know thats an extreme statement, and yes, I know its not likely ever to happen. But its true. Heres why.

1. Most of them dont add anything useful

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are so many people so confused by apostrophes? Because they cant hear them in speech, and they dont serve a valuable grammatical function. They simply mark contraction or possession, and you can tell the meaning without them. If you couldnt, the indignant red-pen-wielding self-appointed correction brigades wouldnt know for sure which ones were wrong because the meaning wouldnt be clear. But they always do know, because the meaning is clear even when the apostrophe is used wrongly or omitted.

Look at common contractions. In the nots — isnt, arent, doesnt, wont, cant, didnt, shouldnt, etc. — most dont have anything they could be mistaken for, and cant and wont are nouns that wouldnt show up in the same places.

In contractions like hes, shes, youre, theyre, and its, there are ones no one gets wrong, and there are ones that are gotten completely wrong all the time (theyre/their/there, youre/your). Either way, people still know what the writer means. Every. Single. Time. The apostrophe makes no difference.

In Ill, youll, hell, shell, well, itll, and theyll, there are some apparent points of confusion. "Ill do it if hell do it and shell do it" might seem like odd English referring to sickness, Hades, and mollusks. But odds are very good you understood it anyway.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And in possessives? Thats where people get them wrong most often, and yet we always know what they mean.

2. George Bernard Shaw did it and so can you

The noted, widely read, widely performed, and highly quotable playwright George Bernard Shaw did away with most apostrophes in published editions of his plays, which include Major Barbara, Arms and the Man, and Pygmalion — which My Fair Lady was based on. Their abolition has done no harm there. I am not using them in this article, and theres no place where my meaning is harmed by their absence. The biggest problem you will run into if you decide to do away with them is that your autocorrect wont want you to.

Yes, there are a few places where there would be a small potential for ambiguity. They wouldnt exactly be the only ambiguous things in English. And theyre small potatoes in comparison to the confusion and general social havoc attendant on the use of apostrophes. Social havoc? Why, yes…

3. Many apostrophes are really only there for condescension

Apostrophes do have one consistent function: The grammar griper brigade likes to use them as the tips on their cats-o-nine-tails. Theyre excellent tools for condescension. Dont tell me theres no classism in terms like "greengrocers apostrophe" (for apostrophes in plurals). Such agitation over a little mark that conveys nothing new — other, evidently, than, "This person doesnt know how to use apostrophes." Its a fashion infraction on the level of wearing white after Labor Day or socks with sandals.

In fact, the apostrophe in the possessive forms is there only because some people wanted to show their superior knowledge. It wasnt there originally. The possessive s in modern English is descended from one of several Old English forms: es, e, an, and a. Only the es form survived — with the e dropped — when English nouns lost most of their inflections. They did not have apostrophes. Meanwhile, the plural forms reduced from as, u, an, a, or nothing to just as (changed to es or s) or nothing. But we got along fine without anything to mark the difference, as we still do when were speaking.

But starting in the 1600s, English writers borrowed the new French model of using an apostrophe to indicate where a letter had been omitted — as in poetic "lov'd," for instance — and some bright sparks decided to put it in the possessive… not simply because there used to be an e there but because they thought that a possessive such as "Toms" was really short for "Tom his"!

You see, there were occasionally occurrences of the "John his house" sort of thing in Old English texts, and it became more popular in Shakespearean times, perhaps because with the dropping of the "h" in "his" it often sounded about the same. Many people wrongly believed that this "Tom his book" form was the origin of the possessive form (ignoring not only history but the fact that the possessive is also s where we would say "her" or "their"). They wanted to put in the apostrophe in possessives to wave around the fact that they knew the truth! Even though they actually didnt.

So, in no small measure, possessive apostrophes exist because some people who were wrong wanted to "correct" people who were actually right.

4. Even where an apostrophe can add something useful, we usually get by without it

There are a few places where apostrophes can be useful. When youre talking about As and Bs or Ps and Qs, they help, but theyre not essential. An apostrophe tells you that the whiskey maker is Jack Daniel, not Jack Daniels, but most people get that wrong anyway. When we talk of decades like the 80s and 90s, an apostrophe before the number makes it clear that weve left off the 19 (or 18), but most people stick the apostrophe before the s instead anyway.

5. They add confusion

I dont just mean that many people are confused about the correct use of apostrophes, though that is true. I mean that some of the uses and non-uses of apostrophes just add to the confusion. Apostrophes are supposed to be markers of possessives, but "its" and "whose" sound like they should have them but — being pronouns — dont. There are also survivals of old genitive forms — when what we now call the "possessive" was used more broadly to indicate association or instrumentality — that dont have apostrophes and people mistake them for plurals, for example "besides" and "anyways" ("anyways" is the older form and means "of or by any way" and is not, as many think, a brainless error "because 'any' takes a singular"). If we didnt put apostrophes on possessives, people might not assume that "anyways" uses a plural.

6. It will free them up for use as single quotes

We wont need to get rid of the apostrophe key on the keyboard. It will be just the quote key: single quotes and double quotes. Then the argument will just be whether you use double quotes first and single quotes for quotes within quotes, as we do on this side of the Atlantic, or the other way around, as they do in Britain.

7. It will make the rules better

Im not talking about taking an "anything goes" attitude to English. Of course we want rules for clarity and consistency (and computers). It also helps if theyre rules that actually get used! We have, many times in the past, either naturally or through some persons influence, changed the rules. English changes all the time. Read Shakespeare, Chaucer, or Beowulf if you dont believe me. English used to do fine without apostrophes, as I have already said, and it can again — as part of the rules. It will even be simpler and more consistent to use. "When do you use an apostrophe?" "Never!" Easy-peasy.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probe

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probeSpeed Read Shawn DeRemer, the husband of Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, has been accused of sexual assault

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein ties

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein tiesSpeed Read The younger brother of King Charles III has not yet been charged

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

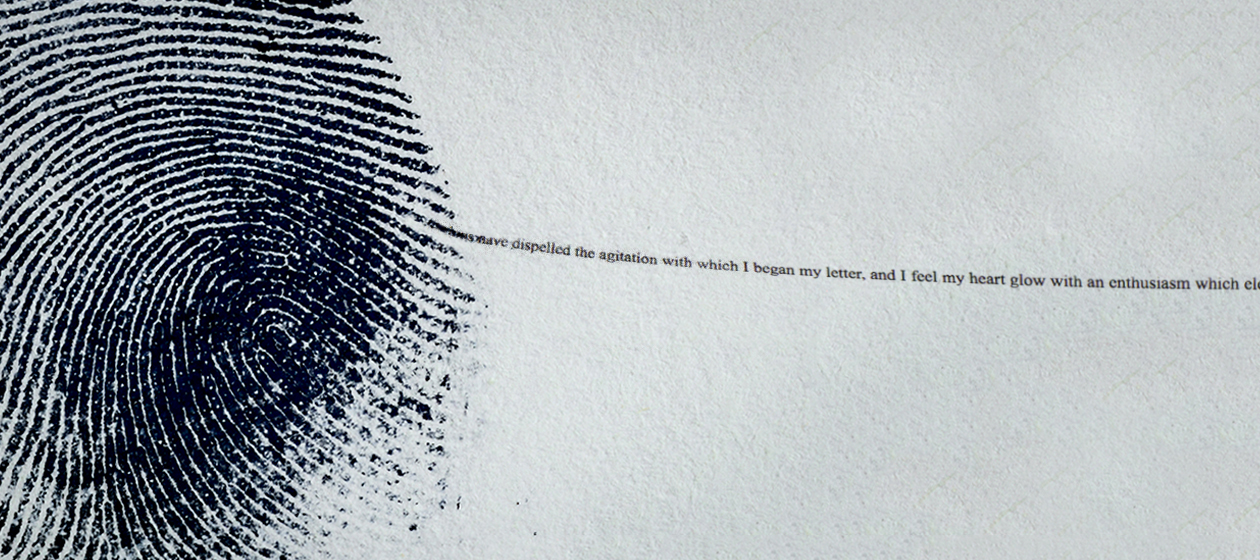

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

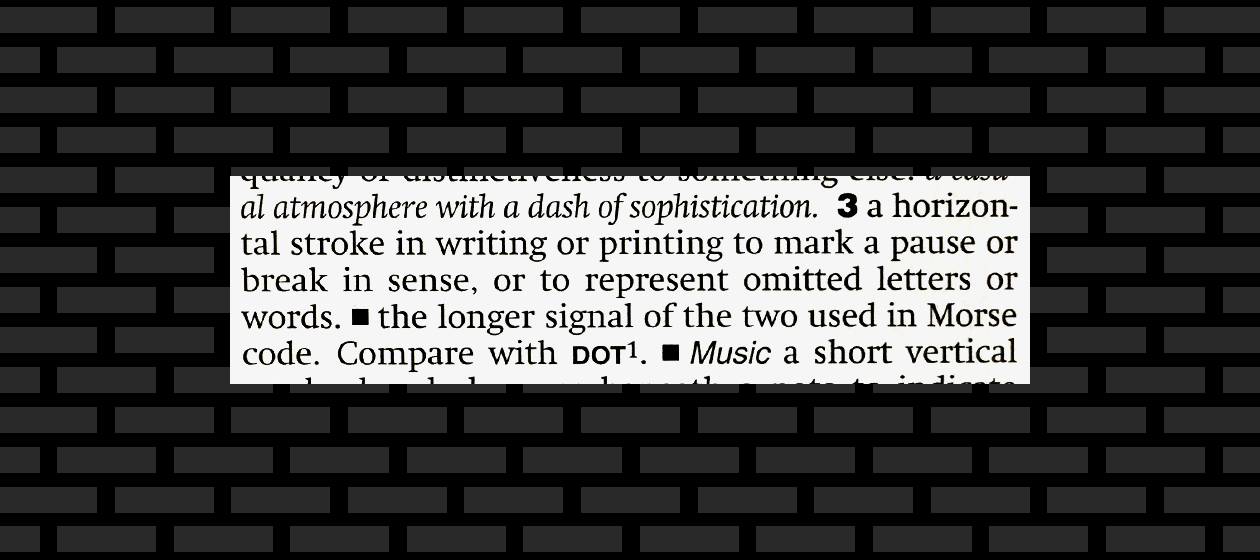

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

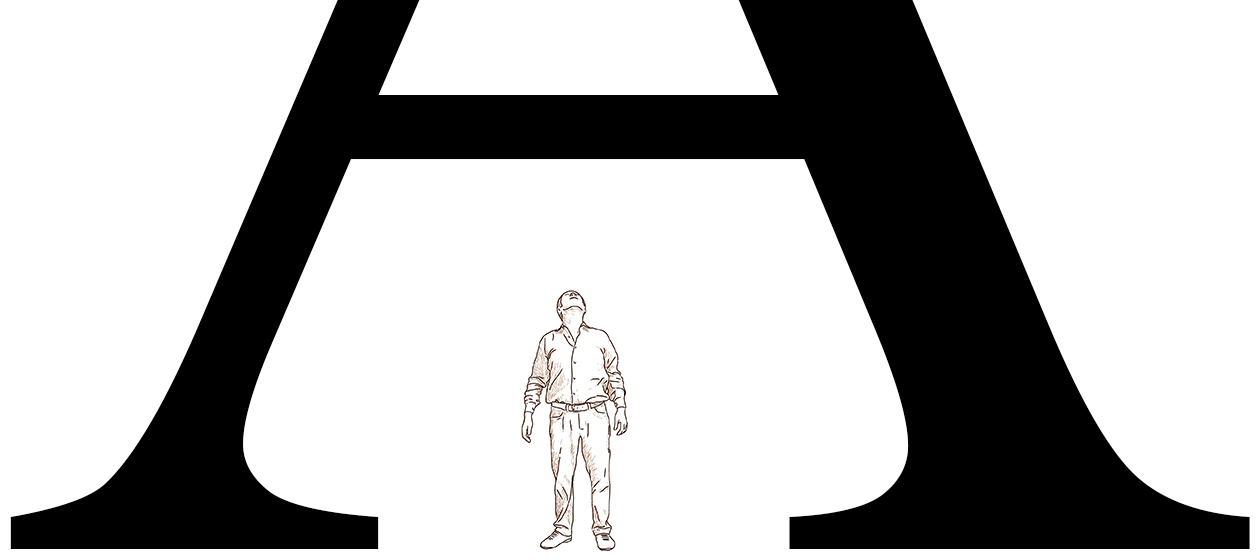

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.