How Obama plans to (finally) close Guantanamo

Four years after taking office, Obama takes new steps toward shuttering the prison

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Days after taking office in 2009, President Obama made good on one of his central campaign promises, ordering that the Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, detention center be closed within the year.

Or, at least he tried to make good on that promise. The delicate politics of the issue — and congressional obstruction — squelched that effort, and the detention center remains open.

On Thursday, as part of a broad speech outlining a narrower vision of American involvement in the war on terror, Obama once again called for the closure of Guantanamo. And this time, he offered specific details on how he'd accomplish that goal, even in the face of legislative opposition.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Calling it a "glaring exception" to the nation's policy of capturing, charging, and trying suspects in court, the president said the detention facility had "become a symbol around the world for an America that flouts the rule of law."

"I know the politics are hard. But history will cast a harsh judgment on this aspect of our fight against terrorism, and those of us who fail to end it," he said. "Imagine a future — ten years from now, or twenty years from now — when the United States of America is still holding people who have been charged with no crime on a piece of land that is not a part of our country."

Central to the president's renewed efforts to shutter the prison was his announcement that he'll end a moratorium on transferring prisoners to Yemen. Obama himself imposed that moratorium in 2010 after the failed Christmas Day underwear bombing, which was carried out by a Yemeni-trained Nigerian.

Of the 86 detainees who have been approved for transfer once certain "security conditions" are met, 56 are from Yemen. Some of those prisoners have been detained for more than a decade, even though they've long since been cleared to return home.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"If we can send the Yemenis home, that could get the ball rolling," one government official told NPR.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the U.S. and Yemen have recently engaged in private negotiations about how to handle those transfers, hence the decision to finally lift the moratorium.

U.S. and Yemeni officials have held negotiations in recent weeks about restarting the transfers, including promising to share information about former detainees. The Yemeni government has said multiple ministries will monitor the ex-detainees to guard against activities that are potentially threatening to the U.S. and to ensure they receive counseling, job training and other aid to help their reintegration into society. [Wall Street Journal]

Yet the decision to again allow Yemeni transfers doesn't completely resolve the larger issue, since it leaves other detainees still in limbo. Starting in 2009, Congress began adopting measures to restrict the transfer of detainees to foreign countries or to prisons in the U.S. — including limiting funds for such transfers — which effectively handicapped the president's ability to clear out the prison.

Obama on Thursday again called on Congress to drop those restrictions, though it's unclear if that plea will go anywhere.

"We need an interrogation and detention policy," Sen. Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.), a vocal opponent of prison transfers, said recently. "Then you can get to the next step of what do we do with Guantanamo."

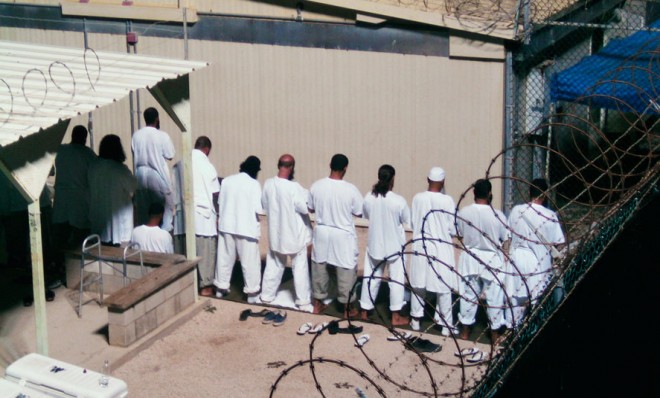

The president's remarks come at a time when more than half of Guantanamo detainees are engaged in a hunger strike. He touched on that point in his speech, noting that detainees had to be force-fed, a practice condemned by doctors and human rights activists as inhumane, and which the United Nations considers torture.

"Is that who we are?," Obama asked Thursday. "Is that something that our Founders foresaw? Is that the America we want to leave to our children?"

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.