Why Michigan Democrats would struggle to recall Rick Snyder

Pro-union forces are furious over the Wolverine State's new right-to-work law. But trying to oust Michigan's GOP governor would be incredibly difficult

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

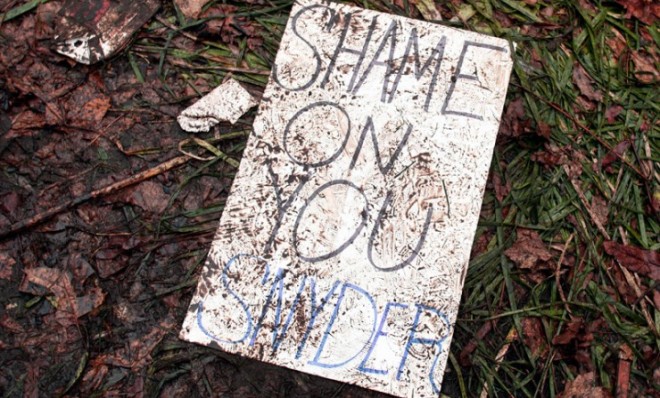

Michigan's quick adoption of a right-to-work law appeared to catch enraged union leaders by surprise. As Michigan is famed for its powerful unions, and since right-to-work laws are seen as a grave threat to unions, drastic political action seems like a strong possibility in the wake of the new law's passage. Already, there has been discussion of recall attempts against GOP Gov. Rick Snyder and members of the legislature. However, due to several factors, including the way Michigan's recall laws are written, these recalls may end up being just idle threats.

This may seem odd. Not only are unions still strong in Michigan — though nowhere near their former peak — but the state has also been a fervent user of recalls in the past. It is almost ground zero for the recent recall boom. Last year it was home to almost 20 percent of the recalls that made a ballot around the country. This year saw a drop-off, but Michigan was still home to 24 recalls. Michigan has also been the home of numerous recalls of state legislators. Four state legislators have faced recalls (two in 1983, the Speaker of the House in 2008, and one more in 2011). Three of those legislators were removed.

The current legislature has recognized the recalls threats, and is now seriously considering significant changes to the recall law, including limiting recalls to only two days a year — primary day and election day.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And yet, there are some serious hurdles that make a Michigan gubernatorial recall (not to mention Senate and House recalls) far less than certain.

This first is the basic fact that unions might shy away from the recall after what happened earlier this year in Wisconsin, where Republican Gov. Scott Walker easily survived a labor-fueled recall election. There is no question that the unions came away the losers in the Wisconsin recall fight. They spent a whole lot of money, and they failed to oust Walker. Despite getting 10 Senate recalls on the ballot over two years, Democrats only won three of the races, and succeeded in capturing the Senate only for a brief time. During their time of brief control, they failed to reverse any of the changes in Walker's union-busting law.

Recalls require money — frequently lots of it. Just getting the hundreds of thousands of signatures necessary to get on the ballot is likely a multi-million dollar endeavor. Without some deep pockets backing a recall threat, it may be next to impossible to get a recall on the ballot. And with the success rate so low in neighboring Wisconsin, Michigan progressives may have trouble drumming up cash to support their own recall movement. For the unions, it may pay just to sit it out and wait till 2014.

A second reason Michigan recalls are unlikely to succeed: Compared to Wisconsin, the signature total would be much greater. Michigan simply has a lot more voters. Wisconsin needed 540,000 valid signatures to force a recall election of Walker. In Michigan, the number to get Snyder on the ballot would be 806,522. The time period is a little longer (90 days for Michigan, as opposed to 60 days for Wisconsin), but not enough to make a gigantic difference. In fact, there have been attempts to recall Snyder, and they have failed by a large margin — one got 500,000 signatures, well short of the 806,522 needed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Michigan's signature total is actually comparable to the amount needed in California to get the Gray Davis recall on the ballot in 2003 — despite the fact that California has many million more residents than Michigan. The reason for the difference is a quirk in the two states' laws. California has one of the lowest signature requirements of any state (12 percent of voter turnout in the last election), while Michigan has a much higher requirement, though one that is pretty standard (25 percent of voter turnout).

A third reason a recall is unlikely: Wisconsin's signature verification laws are much easier. That means Michigan recall supporters would need a bigger cushion of signatures to get their own recall through. Wisconsin only required that the signers be eligible voters; Michigan requires registered voters (as does every other state that has a recall). This registered voter requirement greatly increases the likelihood of failure, and boosts the amount of signatures needed. It also increases the cost of the defense, as more signatures have to be argued over. A general rule of thumb: 15 percent of signatures will be found invalid.

But all of these reasons pale in comparison to the last and biggest one: Michigan's recall laws are much different than in Wisconsin or California. In the latter two states, the replacement vote happens immediately. You vote whether to get rid of the incumbent, and vote on who should replace them all at once. Therefore ousting Scott Walker or Gray Davis would result in a quick change of control. Not so in Michigan.

As it stands now, Michigan has a two-step recall process. First comes the vote on removing the official in question. Months later, the replacement is chosen in a second vote. In the meantime, who replaces the governor? The lieutenant governor. If the lieutenant governor is recalled as well, what happens? For one thing, there would probably be a lawsuit to decide if the LG gets to take the job even though heh or she lost the recall. Then, the next two officials in line if the LG is removed are the secretary of state and the attorney general. Both of those individuals are also Republicans.

One more issue: A successful recall doesn't even end the battle. The second vote could very well go in favor of the Republicans. This just happened in 2011. The unions backed the recall of Republican House Representative Paul Scott. But the Republicans got the last laugh. A new Republican easily won the February replacement vote. The same thing can happen here.

Legislative recalls are much easier to get on the ballot — while there have been only three gubernatorial recalls in U.S. history (and a fourth that was preempted by an impeachment), there have been 36 legislative recalls. Of course, the value of controlling the legislature is much less. The governor still would retain a veto. Even worse, the unions and Democrats would need to recall a large number of officials. Republicans have an overwhelming advantage in the Senate (26-12) and a large enough advantage in the House (58-51). Add into that the fact that the districts have just been redrawn to favor Republican candidates and this obstacle becomes even more daunting.

None of this proves that a recall won't be successful. Despite Scott Walker's victory in Wisconsin, most recalls succeed once they get to the ballot. But the difficulties involved in Michigan suggest that the unions and Democrats will have to think very hard about whether they want to spend the time, effort, and especially the money to try and get a recall on the ballot.

Joshua Spivak is a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College. He writes the Recall Elections Blog.

Joshua Spivak is a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College in New York, and writes The Recall Elections Blog.

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred