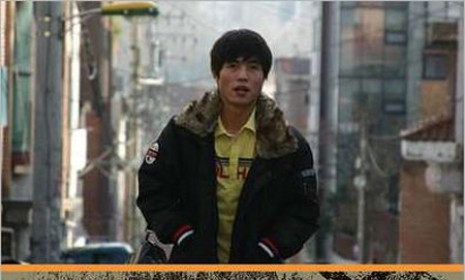

One man's 'astonishing' escape from a North Korean death camp

Shin In Geun was born in prison, but in his 20s, he finally escaped. His story is one that hundreds of thousands of other detainees can't tell

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"His first memory is an execution," begins a riveting excerpt from the new book Escape From Camp 14 about a young North Korean man born and raised in a work camp for political prisoners. Journalist Blaine Harden's book, available at Amazon, tells the "astonishing" story of Shin In Geun, believed to be the only person ever to escape from one of the isolated communist nation's infamous gulags. What was life like for Shin and his fellow Camp 14 inmates? Here, a brief guide:

What was the camp like?

Camp 14 is massive — 30 miles long, 15 miles wide, with its own farms, factories, and mines, and 15,000 prisoners (the U.S. State Department estimates that North Korea has locked up 200,000 so-called enemies of the state). Shin and his mother, who enjoyed the camp's best accomodations, were among the lucky ones, Harden says. They had their own room, shared a kitchen with four other families, and were privileged to get two hours of electricity a day. Still they lived without running water or furniture, sleeping on a concrete floor.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why was Shin in the camp?

His only crime, Harden says, was being born into his family. "The unforgivable crime Shin's father had committed was being the brother of two young men who had fled south during the Korean war," Harden writes. Shin's mother never told Shin why she had been imprisoned.

What was day-to-day life like?

Shin's mother would wake up at 4 a.m. every day to prepare breakfast and lunch. "Every meal was the same: corn porridge, pickled cabbage and cabbage soup," Harden says. After she was done cooking, his mother would work in the fields, planting or harvesting rice in the hot sun. If she met her quota, she was allowed to bring home food. Prisoners rarely talked among themselves — gatherings of more than two people were forbidden, except at executions, which everyone was required to attend.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When did Shin see his first execution?

At age 4. He and his mother were among thousands of prisoners herded by guards into a wheat field, where they watched guards strap a man to a metal pole. They then filled the doomed man's mouth with pebbles, placed a hood over his head, and shot him. Shin would see dozens more executions in later years, including those of his mother and brother. The two of them were executed only after Shin, then 14 years old, turned them in for plotting to escape. Shin's "camp-bred instincts" had taken over, says Harden. Anyone who heard about an escape attempt but said nothing was immediately put to death, and Shin was angry at them for putting his life in danger.

How did Shin escape?

Along with another prisoner on whom he had been sent to spy, Shin devised a rather simple plan: Wait for the right moment, then make a run for it. One day, Shin, then 23, and his friend were sent to trim trees on a mountain ridge near one of the camp's electric exterior fences. The nearest guard tower was hundreds of yards away; patrols were infrequent. When he and the other prisoner dashed for the fence, Shin's accomplice got stuck on the wires, and was electrocuted. Shin crawled over the man's body to safety.

Where is Shin now?

After his near-death encounter with the electric fence, Shin stumbled on a farm, where he found an abandoned military uniform in a shed. He put it on, shedding his tell-tale prison garb, and made his way to the Chinese border. After crossing — he bribed a starving guard by giving him bean-curd sausage, cigarettes, and a bag of sweets — he eventually made it to South Korea, and then the U.S. Shin now lives in southern California, where he serves as an ambassador for Liberty in North Korea, a human rights group.