Irving Kristol?

The polemicist who was the godfather of neoconservatism

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Irving Kristol?

1920–2009

Irving Kristol famously called himself a liberal who had been “mugged by reality.” Beginning in the 1960s, he helped transform that disaffection into the powerful political movement known as neoconservatism. Kristol’s advocacy of anti-communism, small government, and traditional values helped fuel the Reagan revolution of 1980 and was later credited with supplying the intellectual underpinnings of the George W. Bush administration.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As a teenager in New York City during the Great Depression, said the Associated Press, Kristol “was at first similar to so many other children of Jewish immigrants.” He was “passionate about books, allied with the working class,” and outraged by capitalism’s collapse. At City College, he was briefly a Trotskyist. Then, serving in the infantry during World War II, he found himself “surprised by his sympathy for the military establishment.” Kristol soon became a fervent anti-communist and, in a celebrated 1952 Commentary essay, compared liberals who defended communists’ civil liberties to a businessman paying “a handsome salary to someone pledged to his liquidation.” With such sharp, polemical observations, Kristol established himself as a cultural critic. In 1965, he co-founded the quarterly journal The Public Interest, which became the launching pad of neoconservatism.

The term itself, coined by socialist Michael Harrington, was originally derogatory, said The Washington Post. But Kristol seized on it to describe a broad-based movement dedicated to countering “the foment of the Vietnam War and the rise of the counterculture.” Kristol spoused middle-class values and traditional morality, and was suspicious of paternalistic government intervention, which he said often backfired. Thus, he rejected many of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs as expensive, ineffective, and divisive. He touted supply-side economics, which held that “tax cuts would lead to widespread financial prosperity.” He also advocated a strong military.

Kristol’s philosophy found favor in an America shaken by Vietnam and the malaise of the 1970s, said the London Guardian, and he “exerted an extraordinary influence” through a growing “network of magazines, think tanks, and grant-giving bodies.” Many of his disciples—Elliott Abrams, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and William Bennett among them—were central figures in the Reagan administration. Later, a “second generation” of Kristol adherents, led by Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, dedicated itself to “the maintenance of American international hegemony,” helping to lay the groundwork for the invasion of Iraq.

“Sharp, aphoristic, and assertive,” Kristol was hardly doctrinaire, said The New York Times. Though staunchly pro-business, “he criticized America’s commercial class for upholding greed and selfishness as positive values.” He once berated Republicans as “the stupid party” for having “not much more on their minds than balanced budgets and opposition to the welfare state.” He felt that “religion provided a necessary constraint to anti-social, anarchical impulses.” Yet when asked if he believed in God, Kristol responded, “That gets too complicated. The word ‘God’ confuses everything.” Reviewing his shifting allegiances to various political doctrines, from neo-Marxist to neoliberal to neoconservative, he concluded, “I’m going to end up a neo. Just neo, that’s all. Neo-dash-nothing.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kristol’s survivors include his wife, cultural historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, and son William, editor of the neoconservative magazine The Weekly Standard.

-

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sure

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sureTalking Points A weaker dollar can make imports more expensive but also boost gold

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

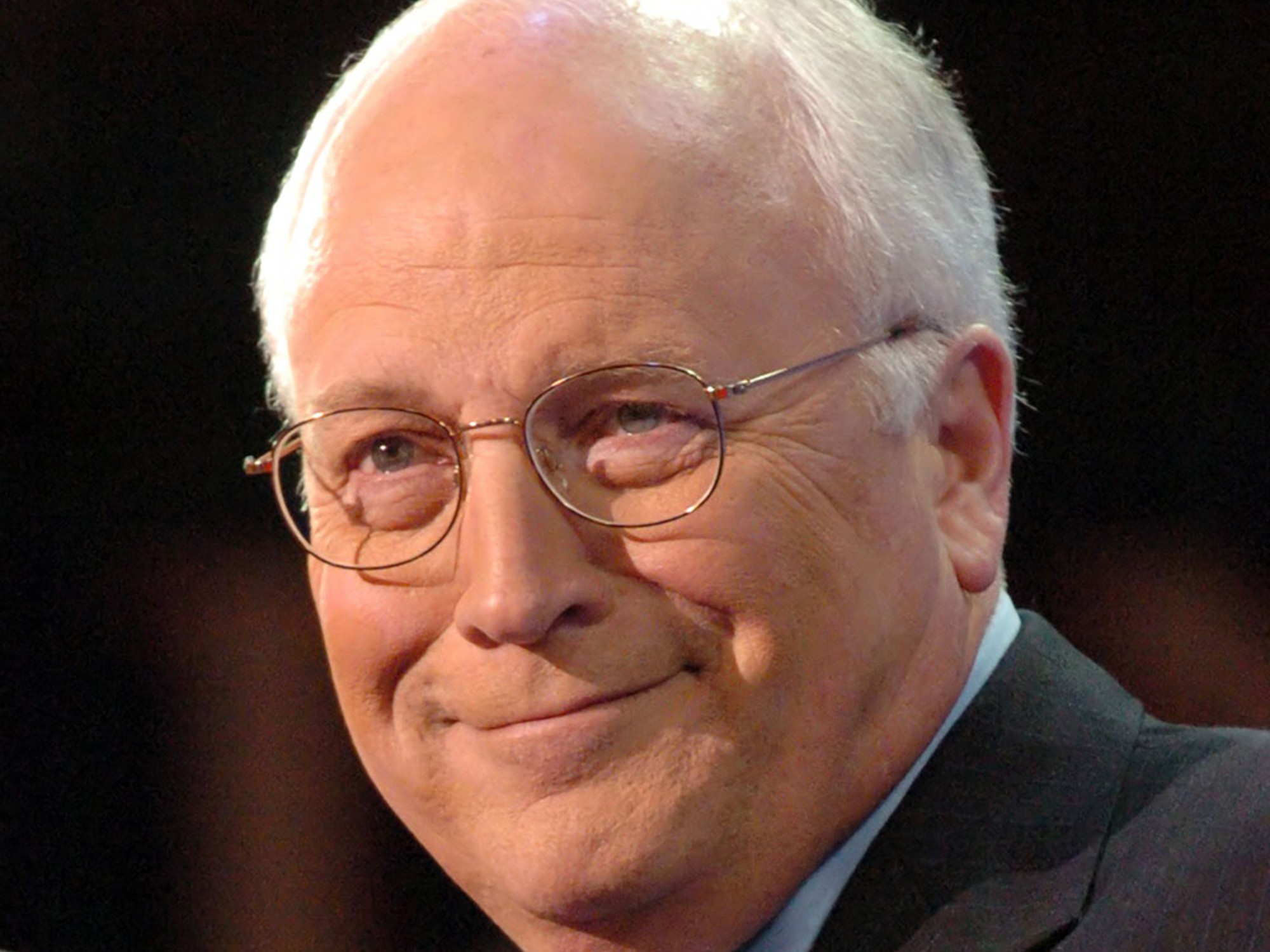

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terror

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terrorfeature Cheney died this month at the age of 84

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

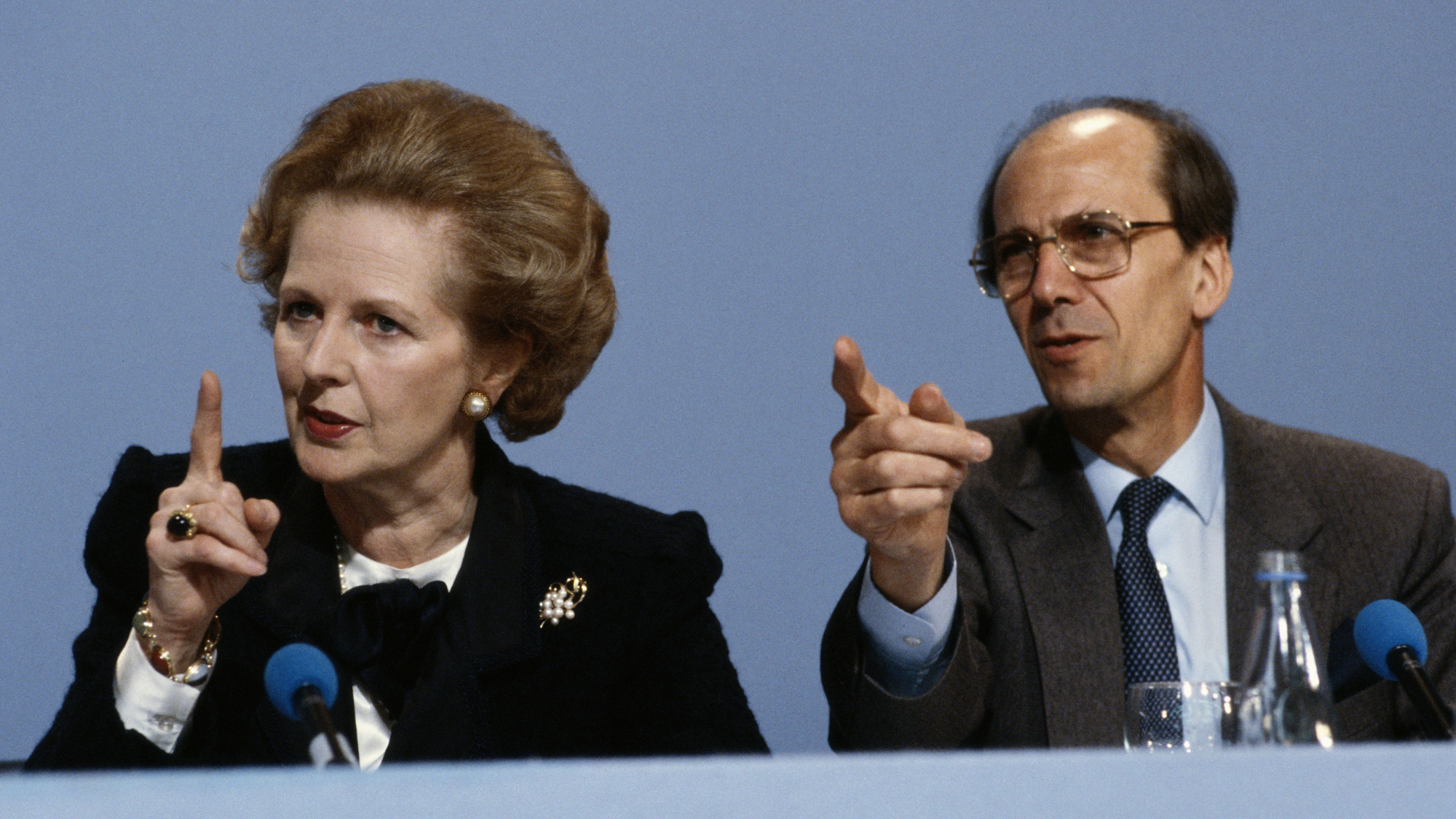

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcer

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcerIn the Spotlight Former Conservative Party chair has died aged 94

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't