2016 Republicans are invoking Ronald Reagan. They're doing it wrong.

The GOP's presidential candidates are drawing incorrect lessons from the 1980s

Republicans are Reaganing again. During his presidential announcement speech last month, Ted Cruz told his Liberty University audience to try and "imagine" they were listening to Ronald Reagan back in 1979 and "he was telling us that we would cut the top marginal tax rates from 70 percent all the way down to 28 percent, that we would go from crushing stagnation to booming economic growth, to millions being lifted out of poverty and into prosperity [and] abundance."

This was not a big ask. The legacy of Ronaldus Maximus, as Rush Limbaugh calls America's 40th president, continues to thoroughly infuse the modern GOP. Like the Force, Reagan's aura surrounds and penetrates Republicans, binding the party's various wings — social conservative, business, tea party, libertarian — together. A generation after Reagan left office and a decade after his death, party politics and policy must still pass through the WWRD — "What would Reagan do?" — filter. This is especially true when it comes to taxes. Just listen to how Rand Paul recently defended his promise of "the largest tax cut in American history" on Fox News:

"The last president we had was Ronald Reagan that said we're going to dramatically cut tax rates. And guess what? More revenue came in, but tens of millions of jobs were created." [Rand Paul]

Good enough for the Gipper, good enough for us.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's natural, of course, for Republicans to keep talking about Reagan, a two-term president whom the plurality of Americans consider the most successful since World War II. After the economic roller coaster of the 1970s, the 1980s began a long expansion of steady growth. Sure, Democrats kvetch about rising inequality and stagnant wages during that period. But median incomes rose by 40 percent in real terms during the 30 years after the initial Reagan tax cuts, and the economy created nearly 50 million net new jobs. If you are a Republican trying to justify deep tax cuts, the Reagan boom sure provides more persuasive evidence than the Bush bust.

But Republicans sometimes misuse Reaganomics to justify fantastical tax plans that promise deep rate cuts for the rich — both Cruz and Paul favor low-rate flat taxes — that will pay for themselves and boost the middle class through explosive economic growth. For starters, the Reagan tax cuts didn't pay for themselves, despite what Paul subtly suggests. Income tax revenue fell from 9.1 percent of GDP in 1981 to 8 percent in 1989. A 2006 Bush administration study found Reagan's 1981 tax cuts lost an average of $200 billion a year, in today's dollars, over their first four years. A 2004 study by two Bush economists estimated that in the long run, "about 17 percent of a cut in labor taxes is recouped through higher economic growth. The comparable figure for a cut in capital taxes is about 50 percent."

Even Reagan's economic team didn't think their tax cuts would be revenue neutral.

What's more, the Reagan tax cuts didn't spur some crazy period of light-speed growth. From 1981 through 1990 — a period including both the 1981 and 1986 tax cuts and ending just before the Bush I tax hikes — real GDP grew by 3.3 percent a year, versus 3.2 percent during the previous decade. Indeed, the Reagan boom occurred in the middle of the "great stagnation" in U.S. productivity that has lasted from the early 1970s until today (other than a period from the mid-1990s through mid-2000s).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now, all of this is hardly evidence the Reagan tax cuts failed. Far from it. Reagan administration economist Bruce Bartlett — a fierce critic of today's GOP — points out that the boost from the Reagan tax cuts helped the economy transition from the high-inflation 1970s with "relatively small economic cost — certainly far less than any economist would have thought possible in 1981." And as Bill Clinton's economic team said in 1994, "It is undeniable that the sharp reduction in taxes in the early 1980s was a strong impetus to economic growth." The "no Reagan tax cuts" counterfactual isn't a pretty one. One could also make the argument that Reagan economic reforms helped set the stage for the go-go 1990s, though Moore's Law may have played a role, too.

Still, today's Republican policy makers and voters have little reason — either from historical experience or empirical studies — to assume tax reform will generate a prolonged period of 4-5 percent GDP growth such that concerns about budget deficits and income distribution are irrelevant. Such imaginings will only suck up intellectual oxygen better devoted to creating a broad portfolio of pro-growth policies — deregulation, education, public investment, labor market reforms, and, yes, some tax cuts — to boost the economy's growth potential. Because that's what Reagan would do in the 21st century. At least I would like to think so.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

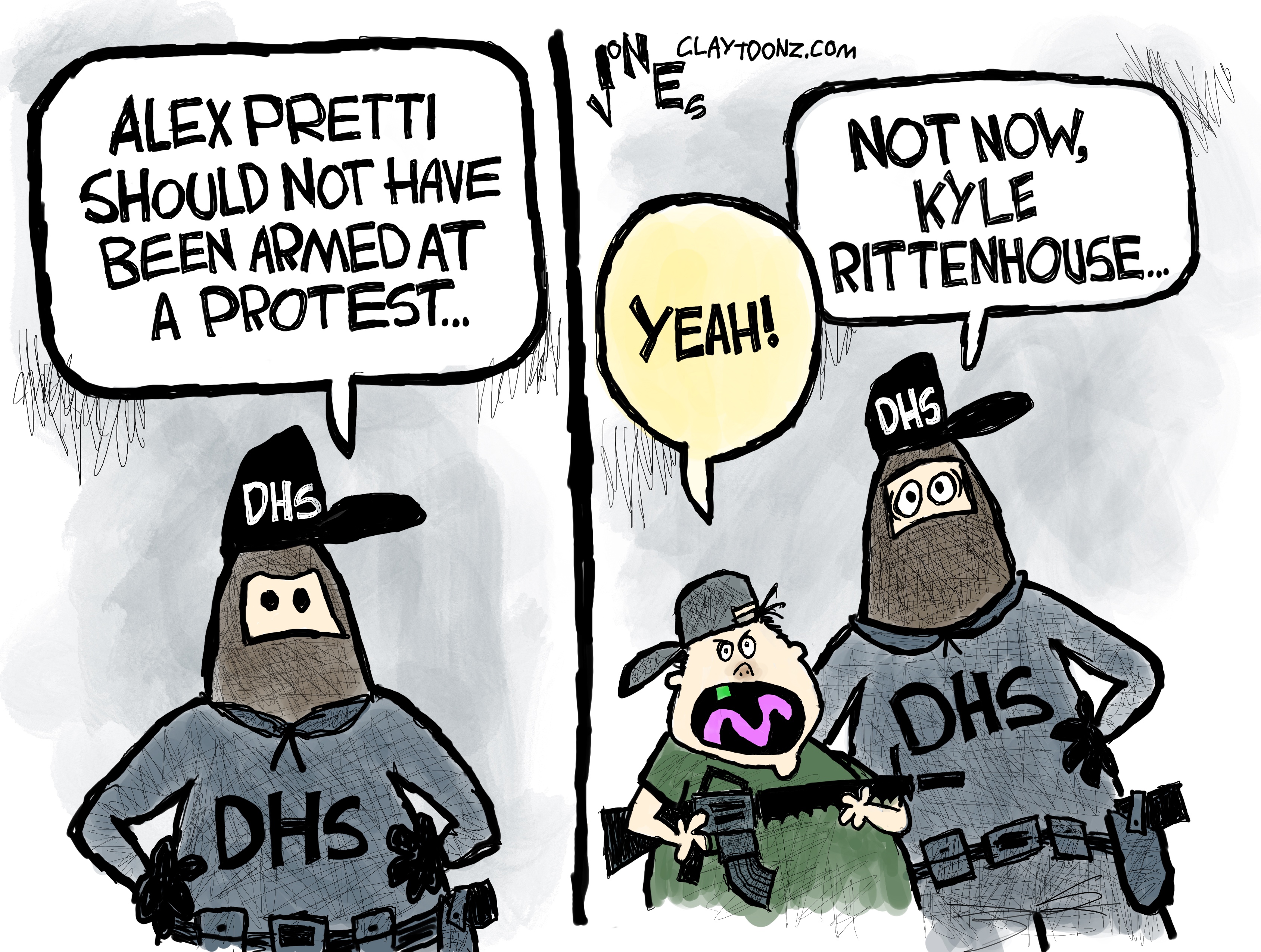

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred