A conservative anti-poverty agenda: Making 'a thousand points of light' work

The final chapter in a five-part series

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

(Read the first four chapters in this five part-series on a conservative anti-poverty agenda here, here, here, and here.)

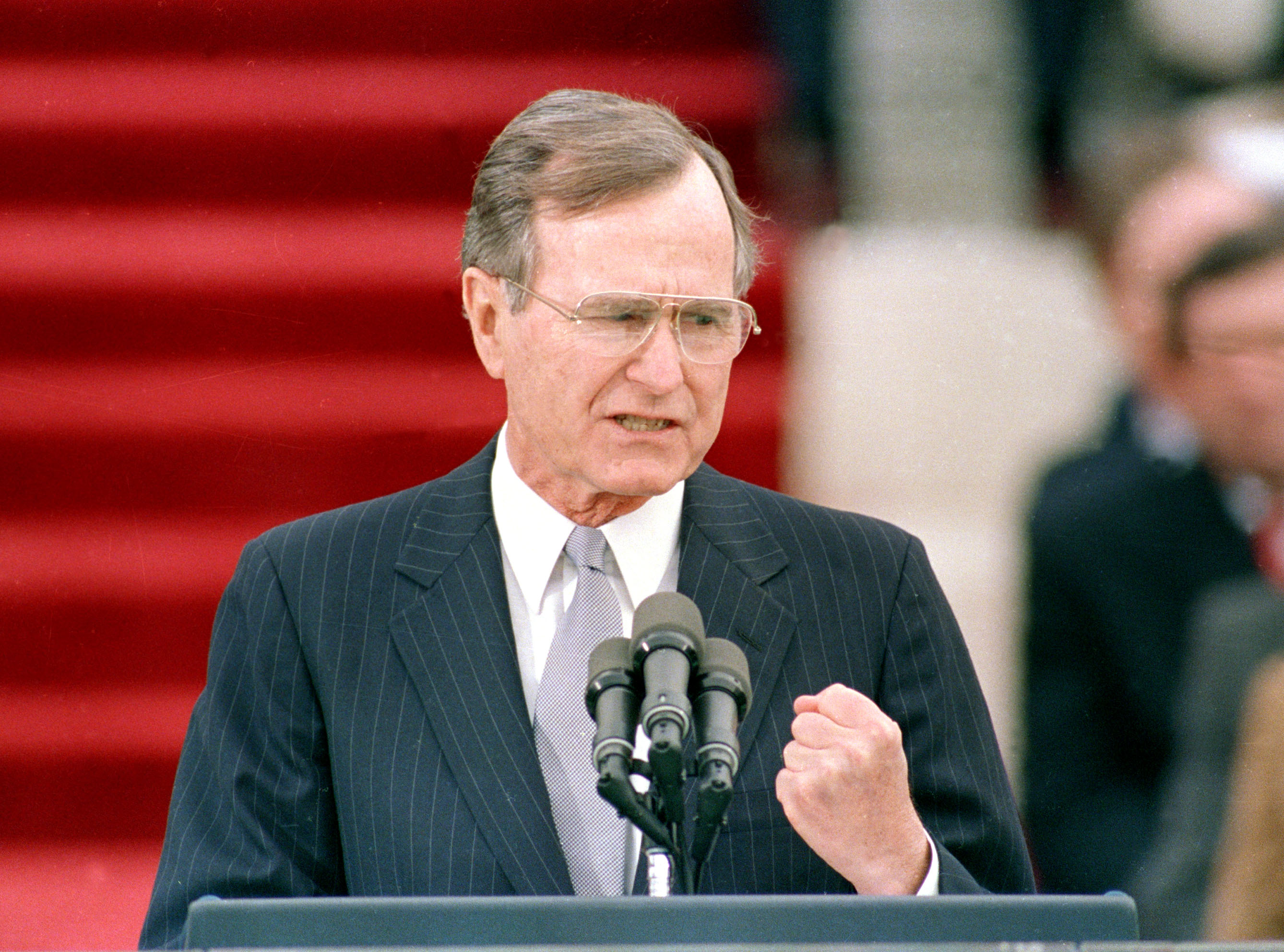

Conservative politicians trying to soften their image are sometimes tempted to talk about poverty. This is what Bush the Elder did when he ran for president in 1988. One of the more notable examples was through his famous "thousand points of light" project. Here's the first President Bush at his inaugural:

I have spoken of a thousand points of light, of all the community organizations that are spread like stars throughout the nation, doing good. We will work hand in hand, encouraging, sometimes leading, sometimes being led, rewarding. We will work on this in the White House, in the Cabinet agencies. I will go to the people and the programs that are the brighter points of light, and I will ask every member of my government to become involved. The old ideas are new again because they are not old, they are timeless: duty, sacrifice, commitment, and a patriotism that finds its expression in taking part and pitching in. [George H.W. Bush]

This community-focused vision of "a thousand points of light" is the right one. What conservatives want, and what all of us should want, is not a "sink or swim" system where the market rules us, but a thriving civil society where private institutions, including the family, religious institutions, private charities, local communities, and, only if need be, state and federal governments, ensure that the basic necessities of life are met for everyone.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The problem with this vision has never been the vision itself — it's how to get there. It hasn't exactly been a roaring success. Yet there are still things we can do.

For example, Rep. Paul Ryan's anti-poverty plan includes the excellent idea of putting the money for anti-poverty programs in a "Flex Fund." It would be funded by the federal government, but leave a lot of room for states and local communities to experiment with the money.

As liberals point out, poverty is an entrenched, structural problem. But precisely because it is such an entrenched, structural problem, we would do well to adopt the conservative virtue of epistemic humility in solving it. Because poverty is such an entrenched, structural problem, the reality is that we know very little about what will help fix it.

We human beings know much less than we think we do. We are also very good at deluding ourselves about that. The great innovations of the modern world work precisely because of this. The scientific revolution was based on the idea of using trial-and-error experimentation to derive practical predictive rules; market economies work better than communism because no one has enough information to be a good central planner; and checks-and-balances government works better than dictatorship because no one has enough information to be an enlightened despot.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It is not just a quirk of conservative ideology to say that, under those circumstances, the best policy approach to fighting poverty is to decentralize decision-making and to encourage experimentation as much as possible.

One reason why we know so little about fighting poverty is because the tools we use to do social science are not up to the job. The way we try to disentangle cause and effect in social science observation is through statistical wizardry, but the problem is that this can never account for omitted variable bias. We never know if we've "controlled" for all the possible factors that might be causing an effect, and so we can never know if we've isolated the right causes. The gold standard for evidence in social science is randomized field trials (RFTs). Because RFTs use a control group, they suffer much less from the omitted variable bias problem. But even then, because social life is so complex, the only way to get reliable insights is through multiple repeated trials.

The government ought to create a program that will match the dollar funding of all anti-poverty initiatives by private charities (including religious institutions), with the precondition that these initiatives be measured through RFTs and the results made public. The goal should be many thousands of RFTs per year. Governments are very good at raising and spending money, and they're very good at creating and enforcing rules. What they are not good at is acquiring information and acting nimbly on that basis. It's why Soviet cars were never brisk sellers on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

The government would therefore act as a platform, empowering private charities, which have the information, and which are decentralized enough to try a bunch of new things. Money would flow to private initiatives, but in a clear, accountable way. Government dollars would match private dollars. And we would get an order of magnitude more, and more reliable, social science data about what works in fighting poverty in a single year than all of what we have at present. The government would be metaphorically "creating a market" in private anti-poverty initiatives, where what works would naturally be rewarded, and what doesn't would fade away over time.

We would really have those thousands of points of lights. Finally.

(Read the first four chapters in this five part-series on a conservative anti-poverty agenda here, here, here, and here.)

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred