The frightening power of our emboldened police

The Freddie Gray investigation shows that the police are more equal than others

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We can debate the "root causes" of the Freddie Gray protests in Baltimore turning violent. Maybe it's poverty, family breakdown, single-party rule, or any number of other things. But the proximate cause is not really debatable: It's a police force that protects itself before the people — and often from the people.

The protests have bubbled across Baltimore ever since Gray, a 25-year-old black man, died on April 19 from injuries, including a broken spine and a crushed voice box, sustained during a half-hour ride in a police van. But why did the protests erupt in an orgy of violence a week later? Under any normal circumstances, shouldn't things have been calming down?

The Baltimore police would have you believe that it was frustrated school kids looking for a fight, and local gangs — inspired by the movie Purge (in which citizens are given a free hand once a year to kill whoever they want) — had hatched a plan via social media to "take out" the police. Whether such a "plan" — which can't be traced to any specific individual or group — existed or not is questionable. But the police's actions seemed to turn it into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

According to various eyewitness accounts in Mother Jones and Gawker, the police blockaded all roads on Monday to prevent young people from gathering. Worse, they prevented area school kids from going home by shutting down a nearby subway station and stopping school buses from leaving, basically trapping the kids. When some kids tried to walk across the street and through a mall to catch the buses on the far side, the police, alarmed by the "presence of juveniles in the area of Mondawmin Mall" confronted them with armored vehicles, buzzing helicopters, and officers in riot gear.

Half an hour later, a full-fledged riot had broken out as kids, who had no way to get home, "popped off" (as one eyewitness put it). No doubt, genuine lumpen joined the melee at some point, looting and pillaging. But initially at least, the kids were "set up" and "treated like criminals before the first brick was thrown," lamented Meg Gibson, a teacher who watched the whole thing transpire.

That's far from the only instance of the cops' self-protectiveness. The entire investigation into Gray's death seems to be a giant exercise in ass covering, aided by what the ACLU calls one of the country's most extreme "law enforcement officers bill of rights."

It's been four weeks since Gray was rushed to hospital in a coma, and the department has yet to offer even a basic explanation of how he sustained his injuries. The cops filed a preliminary report to state investigators, but its promised release to the public has been postponed. Why is it taking so long?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One reason is the "cooling off" — or as The Washington Post's Radley Balko calls it, "getting your stories straight" — period that Maryland cops enjoy, thanks to their bill of rights. During this time, they don't have to answer any questions till they've found a lawyer of their choice — and then only for "reasonable" periods of time in the presence of a union representative. The officer who drove the van has not even provided a statement yet, something unimaginable in an investigation involving a civilian.

In the absence of any real information, the leading theory of how Gray received his massive internal injuries without any signs of an external beating is the practice of "rough riding" that Baltimore cops have been known to use. It involves taking sharp twists and turns at high speeds so that the handcuffed and unbuckled detainee is tossed around in the vehicle. In one sensational instance ten years ago, a librarian was hauled into a police van for public urination — and emerged a paraplegic after he was sent flying face first in the van.

A Washington Post story based on an interview with another detainee in the van with Gray is trying to cast doubt on the "rough ride" theory by suggesting that Gray caused his own injuries by banging his head. That's possible. But it seems rather incredible that Gray, who was barely able to walk and in severe pain when he was shoved into the van, could have hit his head so hard as to break his own neck.

Future investigations will confirm or disconfirm that story — although a leaked medical examiner's report is already doing the latter. Either way, blaming the victim for his own injuries is a tactic that Baltimore cops are certainly familiar with. A chilling Baltimore Sun investigation last September found that in one instance, a plainclothes cop assaulted a young black man getting carryout food, for no apparent reason. The cop broke the young man's nose and fractured his face. Yet in court he accused the victim of injuring himself, an explanation that the jury dismissed before awarding damages.

The Sun investigation found that between 2011 and 2014, the Baltimore Police Department paid about $5.7 million in settlement or court-awarded verdicts to victims of police brutality (and spent an equal amount in legal fees), a figure that would certainly be much, much higher if municipal damages in most instances weren't capped at a measly $200,000. (Cleveland and Dallas have paid between $500,000 and more than $1 million to settle individual police misconduct cases.) Indeed, since 2012, 3,048 complaints have been filed against 850 BPD officers — or nearly 30 percent of its police force. In most instances, the accused officers remain employed because it is very difficult to fire a police officer without an actual conviction, thanks to the police bill of rights and other protections. And most cases don't reach that stage.

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, who has been widely pilloried for her ill-advised remark about giving Gray's protesters the "space to destroy" personal property, has been trying to assert half-hearted control over the department. Whatever her other flaws, she hired a tough new police commissioner with a reputation for controlling police misconduct.

She has also lobbied state lawmakers for reform of the police bill of rights and to pass laws requiring police officers to wear body cameras. She campaigned to make "misconduct in office" a felony, although she hasn't gone so far as to demand the scrapping of the 10-day grace period. But state legislators, both Republicans and Democrats, afraid of the powerful police unions, killed these measures — just days before the Gray encounter.

Addressing Baltimore's socio-economic malaise and giving its Freddie Grays a good life might seem daunting. But preventing their deaths at the hands of the police shouldn't be. That's what Baltimore's protesters are demanding — and that is hardly too much to ask.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

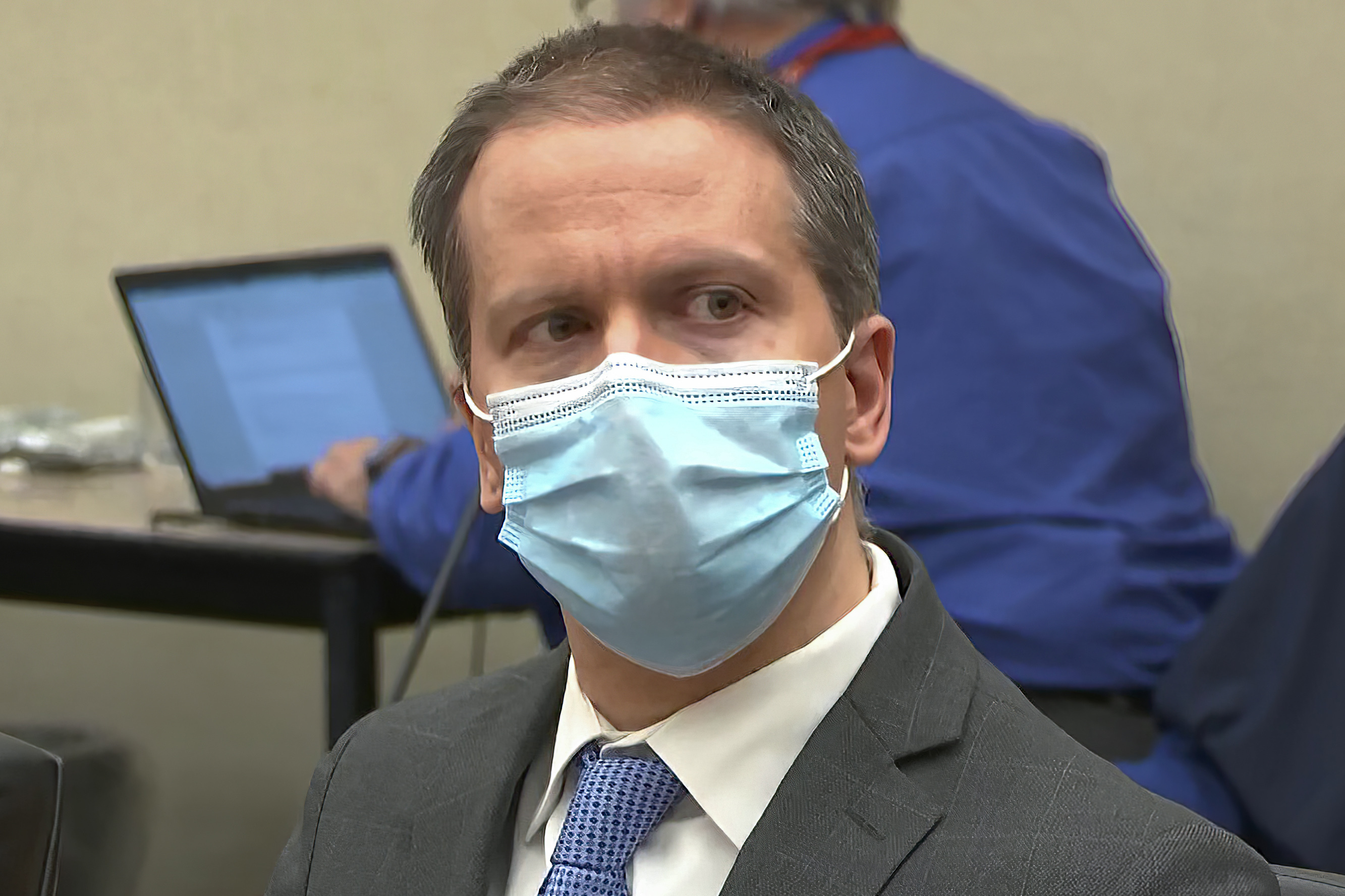

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read