How did political polls become so inaccurate? Blame our obsession with data.

How our obsession with surveys is making surveys more inaccurate

When Nate Silver, the undisputed king of election forecasting, declares that "The World May Have a Polling Problem," it's time to take notice. Why are public opinion polls increasingly proving unreliable?

It seems clear that two things could be happening. Either those who agree to cooperate with the pollsters are unrepresentative of the population, or they are deliberately lying to pollsters about their preferences.

Why on Earth would either of those, or both, be happening?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Because there are so many polls in the field that few "normal" people are willing to answer questions honestly, leaving responses to oddballs or those eager to have a little fun at the expense of the pollster.

Can you blame them? Growing up in the 1970s and '80s, I never recall our household receiving calls from pollsters. Polls started to become a little more common in the 1990s. But in the past decade or so, they've exploded. I don't just, or even primarily, mean calls from professional political pollsters, though there are certainly more of those, including a lot more "push" polls, in which a person (or, more often, a recording of a person) on the phone asks questions not to gauge your opinions, but to shape them in the direction of a particular candidate or party.

But that's just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. I call Comcast to discuss an issue on my bill, and before I reach a human being I'm asked if I wouldn't mind answering a few questions at the end of the call. I take the car in for an oil change, and I receive an email a day later to ask me a few dozen questions about my customer experience — and then a phone call a few days after that, just in case the email ended up in my spam folder. I visit the doctor for an annual check-up, and the phone rings a week later from a firm wanting to know if I'll answer some questions about the appointment. I check the mailbox outside my home and find a letter from the university where I earned my doctorate, asking if I'd be willing to take part in a study of the career paths of Ph.D.'s.

On it goes, month after month, with the polls piling up.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I know, I know: This is nothing but a first-world problem. And I certainly don't want to portray it as more than it is, which is a minor nuisance. Yet it's a revealing nuisance — one that exposes an aspect of the present historical moment that makes it different from earlier eras.

The human mind is limited in its capacity to memorize, organize, sort, and access information, and in the ability to analyze it dispassionately. That's why for all of human history until the invention of the computer, people (including public figures and business owners) made judgments about the world by eyeballing, guesstimating, and generalizing on the basis of sometimes dubious inferences rooted in inevitably partial individual experiences, memories, and subjective impressions, with all of the distortions that go along with them.

Computers, with their vastly superior memory and capacity to analyze vast quantities of information, give us insights that would be otherwise off-limits. That has very positive consequences for social-scientific research, which can now propose and test hypotheses about the shape and contours of The Aggregate — meaning society (or segments of society) viewed as a whole.

But the computer-facilitated compilation and crunching of data also presents an enormous temptation to public figures and businesses, both of which desperately want every added edge they can get their hands on.

In what might be called the classical model of retail democratic politics, the politician goes out on the campaign trail and stakes out positions based on a mixture of what he thinks the people want to hear and what he thinks is best for the country; if the message resonates with voters, they will turn out for him on Election Day. The same holds for a business-owner or entrepreneur: she offers a product or service, and success is determined by sales and whether customers show their satisfaction by returning for more and spreading good word of mouth.

Surveys go much further — into the minds of voters and customers. Knowledge is power, and survey data and analysis grant politicians and those who own and run businesses the power of knowing precisely what the people want, sometimes even before they're fully aware of it themselves.

What's wrong with that? Viewed one politician or business at a time, nothing much. The problem arises when thousands of public figures and marketing departments launch their own surveys to gain competitive advantages. The result is an over-saturated public-opinion marketplace in which citizens and customers alike begin to feel a mixture of fatigue and irritation that dilutes the accuracy of the polls, leading their trustworthiness to get called into question.

That's where we are now, and it's hard to see how we get out of it. Unless, of course, the politicians and businesspeople who've grown so dependent on data take a step back to the ways of old. But that would require a willingness to live with greater uncertainty than today's pollsters, strategists, and marketing gurus think is tolerable.

If I liked your product or service, I'll be back and tell others about it. If I didn't, I won't. If I really hated it, I'll complain to you and maybe spread the word about how awful my experience was. That's how you'll get your feedback, and it will arrive soon enough. In the meantime, leave me alone. The same holds for politicians and parties. Look out at the country, talk to smart people about it, and propose some plans to make it a little better. I'll vote for you if they sound reasonable, and I won't if they don't. That should be good enough.

And hell, as we've begun to see, the alternative isn't perfect information gleaned from a million accurate surveys. It's distorted, misleading information warped by surveys more and more often completed by resentful voters and customers.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Sudoku: January 2026

Sudoku: January 2026Puzzles The daily medium sudoku puzzle from The Week

-

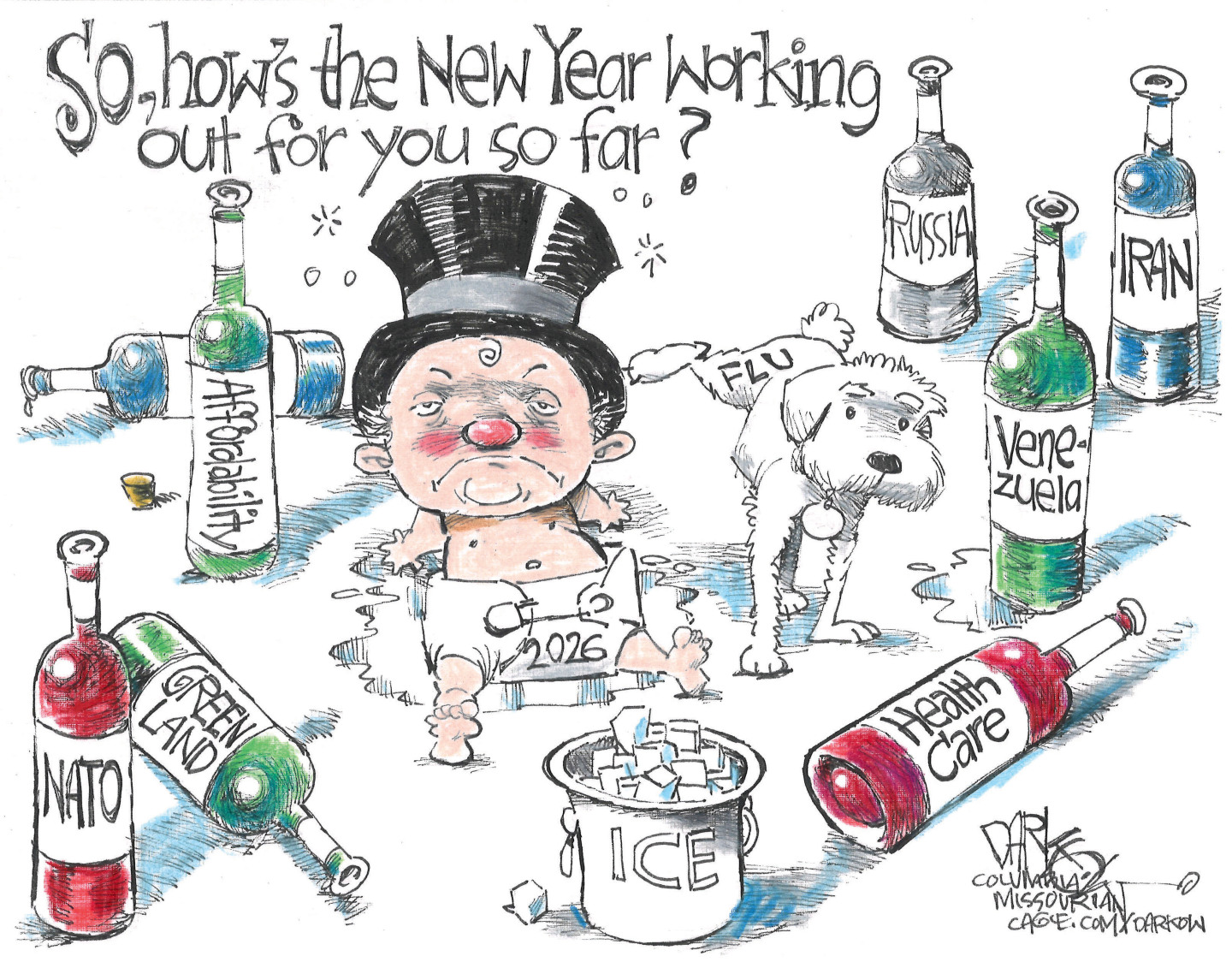

Political cartoons for January 13

Political cartoons for January 13Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include a rocky start, domestic threats, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred