After Charleston, hate crime laws are more important than ever

It makes perfect sense to declare that racially motivated murder is especially repugnant to our values

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the wake of the awful South Carolina shooting, the debate about hate crimes legislation has come back to the fore.

There's a popular view, especially in certain precincts of the intelligentsia, that hate crimes legislation is somehow depraved because it represents "legislating people's thoughts." This view could not be more misguided, and betrays a basic misunderstanding of what the law (especially criminal law) is.

The first problem with this idea can be explained by a basic principle of criminal law: To have an actual crime, you need both a factual aspect and intent. (If you want to get fancy, you can use the Latin phrases: actus reus and mens rea.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The classic first-year law school example is grabbing someone else's suitcase off the carousel at the airport. Did you mistake the other person's suitcase for your own? Or did you want its contents? In either case, the observable facts are exactly the same. But in one case, you have a felony — theft — and in another you have absolutely nothing illegal. The only difference is what goes on in your head at the time of the act.

In other words, every single criminal investigation and every single criminal trial and every single criminal statute involves "legislating people's thoughts" and makes what goes on inside a person's head a key component of a crime. That's not some bizarre deviation from the normal way of doing things, it is the normal way of doing things.

If this seems vaguely totalitarian, think about the alternative. What would happen if you got thrown in jail for long sentences for doing things you never intended to do?

This basic principle of criminal law is a key element of due process. It's there to make it harder to sentence people. In many areas of tort law, the only thing that matters is fact, not intent. If you rear-end someone else's car, it doesn't matter whether you did it by accident — you still have to pay for the damage you caused. Among other reasons, that's because the stakes in civil liability are lower — mere money — than in criminal law, where people's freedom and even their lives are at stake. And so in criminal law, there are stronger due process requirements to find someone culpable.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In other words, the fact that criminal law legislates people's thoughts is not only perfectly normal, it's also a really good thing that helps strengthen due process and protect people's rights.

But there's another, more fundamental reason why "legislating people's thoughts" is totally fine: That's what the law is. It reminds me of another tired and wrongheaded cliché: that we shouldn't "legislate morality." The problem with this trope is that's all that legislation does.

Every single major law is based on a decision that "X" is bad and there ought to be less of it. It's tautological — every law is intended to reach a desired outcome. The reason that outcome is desired is ultimately a reason that is derived from moral principles. Every single law is about morality. Now, there are some things that are immoral but also legal, but the reason is because of a higher moral judgment on, say, the proper role of government.

Here's the point: A key difference between civil and criminal law is that while civil law is there to redress liabilities and material wrongs, criminal law exists to defend a society's values. That's the reason why criminal law is prosecuted by the state, whereas there is no prosecutor in civil law. A civil lawsuit requires a tort, that somebody be wrong. This is not the case in criminal law. Imagine that a homeless vagrant with no family is murdered. You can argue that nobody has been directly wronged by this except for the victim, but being dead, he can no longer bring a lawsuit. Nonetheless, the state will still investigate and attempt to prosecute the murder, because murder goes against our society's values, and therefore must be punished even when nobody alive is wronged.

And that's the real issue here. All murder is repugnant to our deeply shared values, and that is why we make it illegal and we prosecute it. Is it really that crazy to say that murder motivated by racial hatred is especially repugnant to our shared values, and therefore should be punished especially harshly?

There's nothing crazy about that. In fact, it makes perfect sense.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday party

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday partySpeed Read

-

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footage

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footageSpeed Read

-

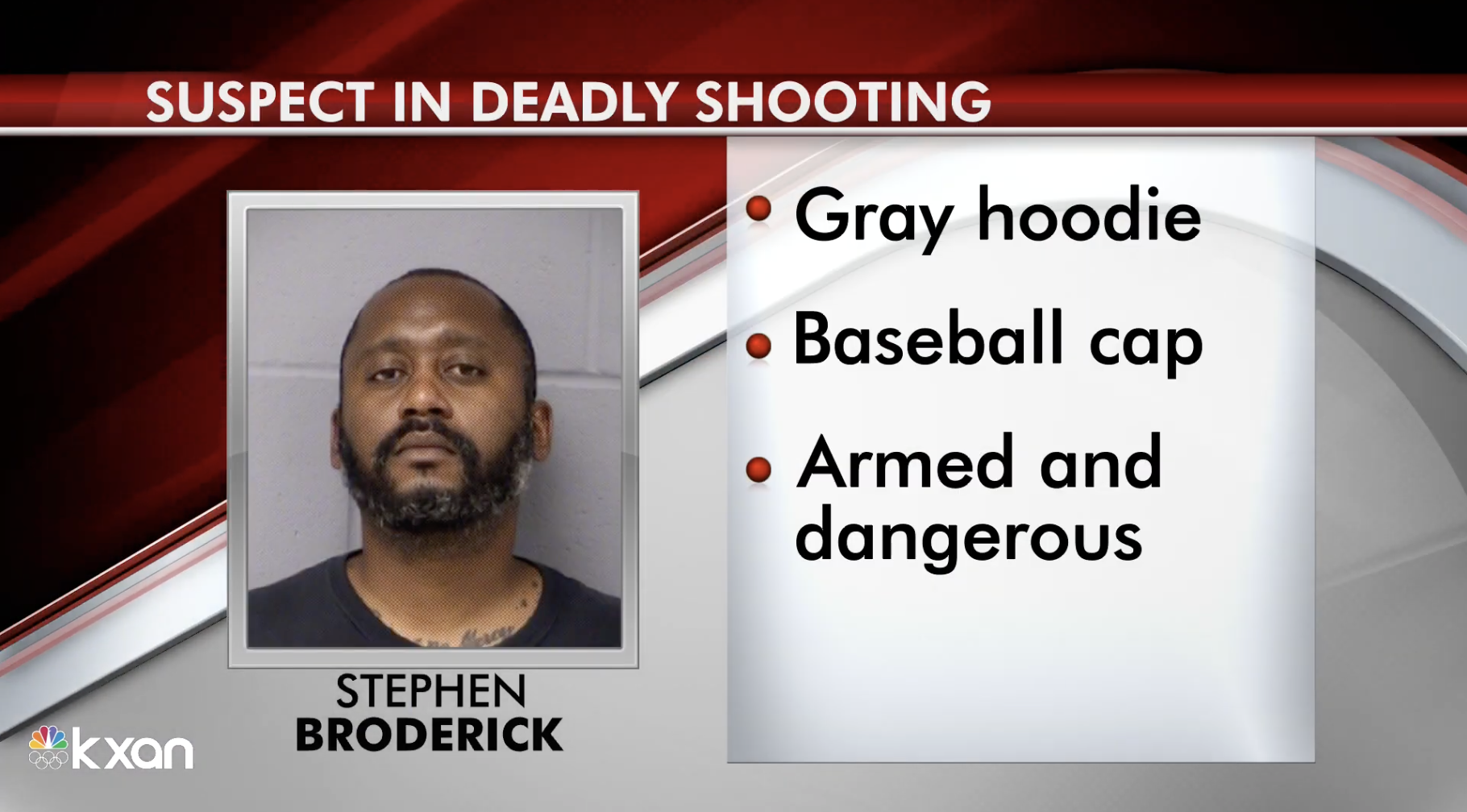

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shooting

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shootingSpeed Read

-

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shooting

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shootingSpeed Read

-

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' case

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' caseSpeed Read

-

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held back

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held backSpeed Read

-

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin Smart

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin SmartSpeed Read

-

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last year

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last yearSpeed Read