Hey, moms: Please don't eat your placenta

For the love of science, put that fork down

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America is home to a small, vocal group of mothers who grant their placenta a reprieve from the medical waste bin — and devour it instead.

You heard that right. The remarkable but ghoulish organ — which forms in the uterus of every gestating woman to help transport and filter food, hormones, and oxygenated blood to a fetus — is now a post-push snack. It can be blended into smoothies, incorporated into dinner, or even dried then ground up and put in capsules. You can perform the necessary apothecary or cooking yourself, or hire a professional placenta preparer to do it for you. Advocates claim that it replaces a new mom's lost iron, supports lactation, and decreases postpartum pain and depression.

I am currently six months pregnant with one baby, plus a healthy, bouncing placenta. But I promise you that not a dollop or grain of anything that once lived in my womb will ever pass my lips. I'm not squeamish — far from it. I even demanded a full-length mirror so I could get better visuals on the birth of my first child. But there will be no noshing on afterbirth for me, unless science says it's beneficial.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And that's the problem. There is no evidence that consuming one's placenta does postpartum mothers any good. A recent scientific review by Northwestern Medicine of 10 research studies on placentophagy (the fancy word for placenta eating) revealed no data to shore up claims that ingesting afterbirth — be it raw, cooked, or in pill form — provides protection against postpartum depression, relieves post-birth pain, increases energy levels, or helps with lactation. In fact, there's not a jot of quality evidence to back any of the supposed benefits. It may even be harmful — to moms and the infants drinking their breast milk.

However, we can't completely ignore the reports from many women who've consumed their placenta and said it was helpful. But anecdotal evidence — and I don't mean to stomp on any individual woman's experience here — is of minimal use when deciding whether a treatment is effective or safe. Mothers who perceived positive results have no idea how they would have fared without that placenta lasagna. Perhaps they would have been just fine.

The placebo effect — in which benefits are felt despite the treatment itself being ineffective — could well be in play here. Which is exciting and useful only if the "medicine" — be it a sugar pill or a capsule filled with powdered placenta — is proven to do no medical harm.

The truth is, we simply don't know what damage this expelled organ, processed or raw, might be doing to our postpartum bodies — or our nursing babies. Add to this the worrying fact that there's no regulation on how placentas should be stored, processed, or dosed. Without this, women have even less assurance that what they're swallowing is safe.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Our sense is that women choosing placentophagy, who may otherwise be very careful about what they are putting into their bodies during pregnancy and nursing, are willing to ingest something without evidence of its benefits and, more importantly, of its potential risks to themselves and their nursing infants," said the review's lead author, psychologist Cynthia Coyle.

But it's no wonder that American woman are looking for DIY ways to boost their health after having a baby. Postpartum support in the U.S. is embarrassingly nominal. After a normal delivery, you're observed in hospital for a couple of days; later you might receive a phone call from a maternity nurse, who's reading questions off a sheet. Then, there's a six-week wait until you're next seen by a doctor. Considering that an estimated 50 percent of new mothers will experience some form of "baby blues" after birth, with 10 to 20 percent suffering a more severe form of postnatal depression, the supervision we receive is worryingly inadequate.

Still, I implore all new mothers to hold off on potentially harmful placenta-munching until there's a side order of supporting data to go with it.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

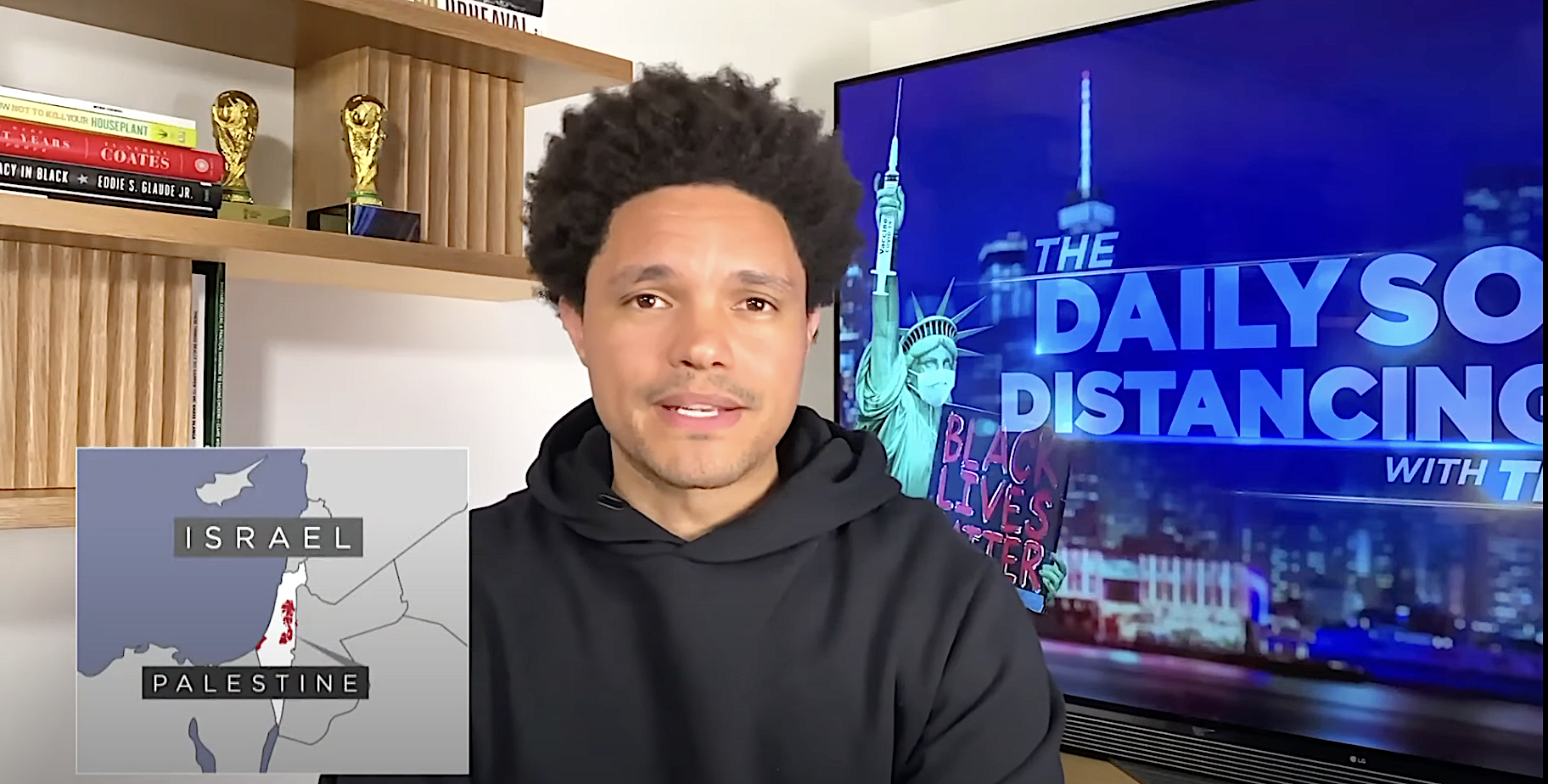

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read