Star Wars and the new economics of movie making

It's all about familiar characters and bankable franchises

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You may have heard a thing or two lately about a little movie called Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

Of course, this cinematic juggernaut has been stampeding through movie theaters and crushing box-office records like a pack of hungry rathtars. It's the seventh installment in a much-beloved space opera, and for the record, it's worth seeing.

Disney and Lucasfilm not only have two more Star Wars movies lined up to finish off a new trilogy, they're also planning two or three standalone films set in the Star Wars universe. Nor do they intend to stop there: They aim to release a new Star Wars movie every year as long as ticket sales keep justifying it, reports Wired.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The looming possibility of Star Wars forever and ever represents the final culmination of a major change in how Hollywood does business. Sequels, or movies pulled from established products and franchises, have always been a part of American cinema. But Mark Harris pointed out last year that even as recently as 1999, only four of that year's top 35 box-office hits were sequels. By 2014, it was 12 of of the top 14. From now until 2020, we'll be facing a veritable flood of continuations to major franchises like Avatar, Terminator, Mad Max, and Pirates of the Caribbean, along with films based on DC and Marvel comic book heroes.

"In 2014, franchises are not a big part of the movie business," Harris wrote. "They are not the biggest part of the movie business. They are the movie business."

Set aside the artistic merits of all this. Practically speaking, how on Earth did it happen?

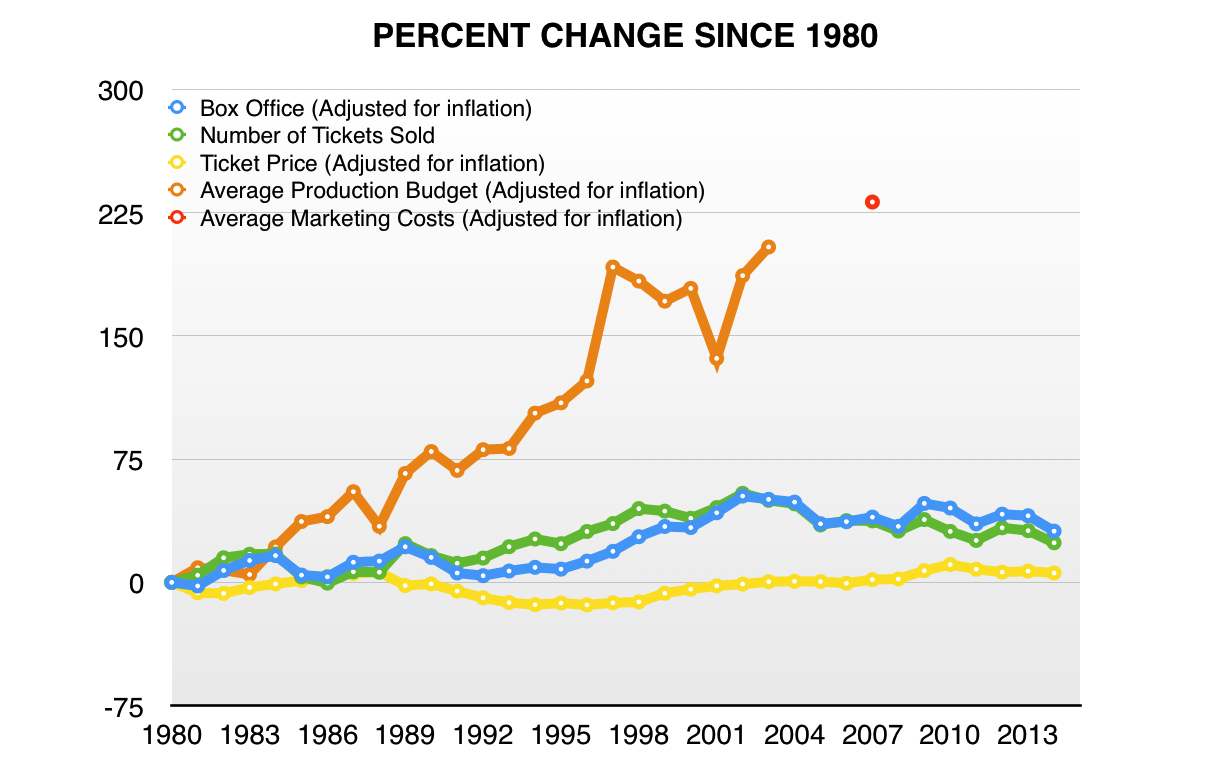

Let's begin with the basic economics. If you poke through the numbers at Box Office Mojo, domestic ticket sales rose from roughly 1 billion tickets in 1980 to a peak of 1.58 billion in 2002. They've since declined to 1.27 billion in 2014. In today's dollars, domestic box office went through a similar pattern: $7.9 billion in 1980 to a $12 billion peak in 2002, and down to $10.3 billion in 2014. Ticket sales and gross revenue topped off at 52 to 54 percent higher than the 1980 base, and are now 24 to 31 percent higher, respectively.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Despite our collective angst over the seemingly exorbitant cost of 3D tickets and high movie prices in major cities, when you adjust for inflation, ticket prices haven't changed much at all over the same period — and remain cheaper today, in real terms, than they were around 1970.

It's budgets for production and marketing (the latter of which can almost double a film's costs in some instances) that have gone through the most dramatic change. Box Office Mojo provides production budget numbers only up to 2003, but adjusting for inflation they increased by a whopping 200 percent since 1980. I could only find marketing budget numbers for 1980 and 2007, but between those two years they increased by over 230 percent.

(Graph by author, data from Box Office Mojo and The Hollywood Reporter.)

This certainly reinforces a story in which movies got more expensive, which forced studios to make less of them, which forced marketing costs way up because now each movie's success is more critical. Hence Harris' thesis is that the fundamental business point of relying on sequels and established franchises is risk avoidance.

Lots of Hollywood insiders — including J.J. Abrams, who directed The Force Awakens — lament out-of-control budgets. And while budget-busters have always been with us — Cleopatra would've cost over $200 million in today's dollars and almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox in 1963 — 45 of the 50 most expensive films ever in inflation-adjusted terms were released in the last decade.

Filmmaking involves lots of highly paid professionals, from screenwriters and directors to lighting crews, set designers, computer effects artists, and the armies of agents and lawyers behind every major star. Then there are the oodles of marketing professionals and designers behind the ad campaigns. So films become more expensive as the wages for those professionals pull away from the bulk of the country.

But that's not the whole story, and it may not even be most of the story.

What these numbers don't capture is everything that's changed around the film industry. In the mid-20th century, television was primitive and there was no home video market. People went to the movies or they went home to the nightly news. While comprehensive data is hard to come by, these days theatrical box office is a minority of the revenue for the big studios. Sales from home video, DVD, Blu-Ray, streaming, and the cash flow from licensing movies to television are all considerably larger. International markets have also exploded. It's critical how The Force Awakens plays in Europe, Japan, China, and elsewhere as much as it's important how it plays here at home. Films like Troy, Daylight, Terminator Genisys, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, and even The Counselor all did modest to poor box office domestically, but more than made up for it overseas.

Decades ago, theatrical Hollywood movies relied on an almost solely American audience that enjoyed few other options for entertainment. Today, Hollywood is trying to cash in through theaters, video sales, and digital distribution, to a multinational, multicultural audience that also has thousands of channels of cable and the internet to occupy themselves with. That explains those declining box-office revenue numbers and ticket sales.

So to survive, Hollywood now has to compete and market itself far more ferociously than it did before. And that means it needs to make movies that are easily marketable. Hello, movies with recognizable heroes, established worlds, and already beloved stories. Independent character studies don't fit the bill. Comic book adaptations and big action and comedy franchises with world-famous stars do.

Hollywood also has to make movies that are easily marketable internationally. Smart and original dramas usually have to rely heavily on the specific contexts of their particular culture, while robots, wizards, sword fights, space ships, superheroes, aliens, massive battles, and lots of explosions are a universal language.

Making movies has certainly gotten more expensive. But the world also forced Hollywood to start making more expensive movies.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.