The secret history of cowboy socialism

Sorry, Ammon Bundy: The West was actually won by Big Government

Few figures of American myth are more iconic than that of the American cowboy: The rugged pastoralist, squinting down from atop a faithful horse and underneath a faded Stetson. The man who can build a fire in the rain, break a horse, de-horn a bull, ride all day chasing steers, mend a fence, set a broken bone, build a cabin from cut logs, and still make it home in time to cook up a round of steaks. The man who tamed the last frontier, the great American West. He's perhaps the signature encapsulation of the American spirit of self-reliant individualism.

For an example of someone who clearly subscribes to the cowboy legend, look no further than the insurgent Ammon Bundy, leader of the ragtag militia that has occupied the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Oregon for the past few weeks, with his beard, felt cowboy hat, and flannel shirts. His demands, though kooky, are straight out of the individualist tradition as well: an end to federal interference with the West, particularly government ownership of land.

Bundy's ideas are nonsense — but they're no more wrong than the entire creation myth of the American West. Though there have been Americans who could survive completely unaided in the West — men like Kit Carson and Jim Bridger — there were only a handful of them, and most were at least half-crazed. No society on Earth has ever functioned wholly on self-interested individualism — and that holds doubly true for the West. From the very start to the present day, Big Government has been the very bedrock of the settlement of the American frontier.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Before the West could be won, it first had to be stolen. Mexico still claimed sovereignty over most of the territory, so U.S. President James Polk ginned up a quick war to steal half of the unlucky country. Even afterwards, there were still tons of Indians living in the conquered territory, so U.S. authorities had to undertake a general program of ethnic cleansing to make way for white settlers. Smallpox had done the bulk of the heavy lifting there, but extensive white settlement still required the first major domestic government program in the West: the Indian Wars.

In the West, these were a series of conflicts that began after the Civil War, as the reunited nation looked to digest the enormous territory it had recently swallowed. Not really wars in the traditional sense, they were more a series of battles, skirmishes, and massacres all driven by the same thing: white desire for land, and native desire to stay where they'd been for the last few thousand years. They all ended the same way — with the U.S. Army crushing the Indians and forcing them to sign a treaty giving up great swathes of land, which generally would be immediately breached by whites, sparking another war and another land grab.

Once the Indians had been driven out (save for a few pitiful reservations composed of the most unproductive land in the region), white settlement was stoked with the first example of genuinely socialist policy: free land. A long series of laws gave sizable chunks of land (classically a quarter-section, or 160 acres) to individuals subject to proof that they were putting it into agricultural production. Railroads also got vast chunks as a way to fund new transportation, and mining companies could claim smaller bits with mineral reserves.

This was socialist both in the "free stuff from the government" sense and the Soviet sense, in that the land programs were conceptually unworkable, catastrophically mismanaged, and riddled with fraud. For places with decent precipitation, 160 acres is more than necessary — indeed, far too much for a single family to farm without the aid of modern heavy machinery. But for ranching — and not all that much of the West is suitable for farming without irrigation projects — 160 acres is far too little, only enough for a handful of cattle.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

John Wesley Powell, first head of the United States Geological Survey, suggested a more rational approach: vary land grant size based on precipitation — smaller for rainy areas, much, much larger for drier ones — and ensure that every new homestead had at least some water. He was shouted down by angry Western politicians who refused to accept that their states could be as inhospitable as he claimed. As a result, regular people were largely frozen out of the land grants, while crooks and rich tycoons amassed huge holdings through fraud and legal chicanery.

As Marc Reisner details in his history Cadillac Desert, this is the basic problem with Western politics, even up to the present day. It has been from the very start handicapped by the reality that only extensive federal government projects could possibly facilitate the settlement and development of the region, but it has been too wedded to the cowboy mythology to admit it.

But instead of coming to terms with reality, and building quality government institutions to ensure the programs functioned properly, Western politicians simply grafted massive federal subsides onto their beloved cowboy individualism. Unsurprisingly, the result was usually poor.

After the end of the homesteading era, the government asserted federal control over the remaining unclaimed land. Some was reserved for national parks and monuments but, as Christopher Ketcham writes, the bulk of it was turned over to agencies like the Grazing Service and the General Land Office, which would eventually become the Bureau of Land Management. Under Western pressure, these were immediately captured by the big ranching barons, granting them grazing rights at a fraction of the market rate (meaning much of the management work carried out by these agencies had to be paid out of federal coffers). The effects on the land's long-term health were disastrous.

This brings us to the final and starkest example of Western socialism: the delivery of water. What people tend to forget in the age of electricity and automobiles is that the West is mostly a huge desert, some of it harsh in the extreme. Private and even state-level efforts to develop water resources sufficient to support Western agriculture and mass settlement repeatedly failed all throughout the Gilded Age, leading to the passage of the Reclamation Act in 1902. It would end with the government building, owning, and operating key economic institutions throughout the West.

Government water projects through the 1920s were largely a mess, as inexperienced bureaucrats ran headlong into the difficult realities of Western country. But the Great Depression marked a turning point. The West found in the New Deal a political movement ambitious enough to attempt the most promising water projects, which were truly massive, and momentum was further stoked by World War II's vast appetite for electricity to smelt aluminum. Practically overnight the Bureau of Reclamation was building some of the biggest structures ever attempted — Hoover, Grand Coulee, Shasta, and Bonneville dams, plus a slew of smaller projects — at the same time. These projects were generally completed under budget and ahead of schedule, and made reasonable policy sense. To this day Grand Coulee is the largest single electricity source in the entire country.

However, this moment of rational ambition was brief. After the war was over, with Western states growing in population and their congressmen occupying key committees, the old pattern reasserted itself. Western politicians — often including the most hardcore conservatives in Congress, like Barry Goldwater — demanded water projects for cities and agriculture. These were as a rule preposterously uneconomical, sometimes even designed to produce crops the government was paying farmers elsewhere not to grow (due to price-crushing surpluses). The government built them anyway, paid for some of the deficit out of hydropower revenues, and Congress contributed the rest. For half a century water projects were one of the primary venues for pork-barrel politics, papered over with a patina of John Wayne nonsense. As Reisner writes:

But even as the myth of the welcoming, bountiful West was shattered, the myth of the independent yeoman farmer remained intact. With huge dams built for him at public expense, and irrigation canals, and the water sold for a quarter of a cent per ton — a price which guaranteed that little of the public's investment would ever be paid back — the West's yeoman farmer became the embodiment of the welfare state, though he was the last to recognize it. [Cadillac Desert]

By the 1950s all the best projects had been built; by the late 1960s all the worst ones had too. Faced with a rising tide of environmentalist fury, and basically out of places to build, the water projects machine eventually collapsed. Now, after over a decade of climate change-induced drought, the West is grudgingly attempting to reorganize its hideous water system along saner lines.

It's hard going, and one reason is the cowboy political tradition represented by Ammon Bundy and his pack of revolutionary wannabes, who want to pay zero in federal grazing fees and end the federal ownership of land. Even reformist Western politicians still have to tiptoe around the fact that the federal government is simply an inextricable part of how the West functions and has been since the beginning. That Bundy has confused one of the primary spigots of rancher welfare with a rancher-smashing tyranny is only a wild exaggeration of a typical view, rooted in Western myth and broader American conservatism.

Until the West can get over its childish insistence that it can too become self-reliant, or that the federal government which supports it is somehow illegitimate, it will continue to struggle with patchy development and inept governance.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Zimbabwe’s driving crisis

Zimbabwe’s driving crisisUnder the Radar Southern African nation is experiencing a ‘public health disaster’ with one of the highest road fatality rates in the world

-

The Mint’s 250th anniversary coins face a whitewashing controversy

The Mint’s 250th anniversary coins face a whitewashing controversyThe Explainer The designs omitted several notable moments for civil rights and women’s rights

-

‘If regulators nix the rail merger, supply chain inefficiency will persist’

‘If regulators nix the rail merger, supply chain inefficiency will persist’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

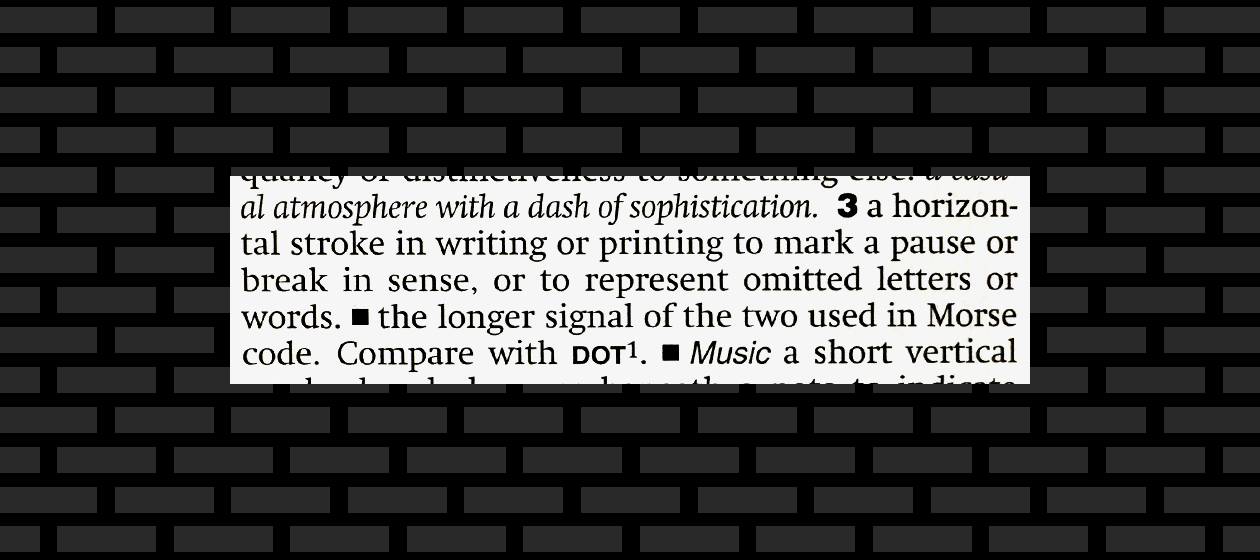

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.