This might be the end of organized labor

Oral arguments earlier this week indicate the Supreme Court may take a big whack at American unions

The U.S. Supreme Court may deliver a big blow to organized labor in America. On Monday, the court heard oral arguments in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a case whose importance to public sector unions can hardly be overstated. If the oral argument was any indication, public sector unions are out of luck.

Friedrichs concerns the constitutionality of "agency shops" for workers providing government services. In an agency shop, people working under a collective bargaining agreement negotiated by a union are free not to join the union, but are required to pay the equivalent of the union dues. That's because without the rules of an agency shop, workers could get the benefits and protections of union membership without bearing any of the costs.

In 1977, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld agency shops in the public sector, subject to some restrictions. Unions could collect dues from non-members, but only for purposes related to employment and collective bargaining. Non-members could opt out of money used for political purposes.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Republican Party, and hence a Supreme Court that has been largely controlled by Republican nominees since early in the Nixon administration, has moved far to the right since 1977. And the Roberts court has been chipping away at public sector unions. In the 2012 case Knox v. SEIU the court held that merely allowing non-members to opt out of political contributions violated their First Amendment rights. The court ruled that unions had to affirmatively get the consent of non-members to use dues for political purposes.

But that wasn't enough for opponents of labor. In 2014, in Harris v. Quinn, the court went further, arguing that agency shops violated the rights of home health care workers. In Friedrichs, the plaintiffs are essentially trying to make public right-to-work laws a constitutional requirement. The court is being asked to simply rule agency shops unconstitutional, full stop. This would starve unions of resources.

In theory, public sector unions should have had a reasonable chance of prevailing in the court. Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy have long held that the First Amendment rights of public sector employees should be minimal. In 1990 case, Scalia and Kennedy dissented from an opinion holding that it violated the First Amendment rights of public employees to be required to join the Republican Party as a condition of employment. If public sector employees can be compelled to join a political party as a condition of employment, it's essentially impossible to argue that they can't be required to pay dues for the benefits they receive from union representation.

But to be optimistic about Scalia and Kennedy assumes that they will put principle above politics. Alas, there's little reason to believe this. Most famously, Scalia and Kennedy's argument that the Affordable Care Act was unconstitutional was plainly inconsistent with Scalia and Kennedy's prior holding that the federal government could seize homegrown medical marijuana not intended for distribution. Indeed, the inconsistencies were so flagrant that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's opinion holding the ACA constitutional in its entirety cited Scalia's earlier opinion chapter and verse.

Monday's oral arguments seem to make it clear that Scalia and Kennedy will decide the case based on the interests of the Republican Party rather than on their previous First Amendment doctrines. Both were relentlessly hostile not just to the arguments made on behalf of public sector unions, but to the unions themselves. Anybody holding out a hope that they may feel constrained by their previous opinions is surely disabused of the notion now.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Scott Lemieux is a professor of political science at the College of Saint Rose in Albany, N.Y., with a focus on the Supreme Court and constitutional law. He is a frequent contributor to the American Prospect and blogs for Lawyers, Guns and Money.

-

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymandering

Gavin Newsom mulls California redistricting to counter Texas gerrymanderingTALKING POINTS A controversial plan has become a major flashpoint among Democrats struggling for traction in the Trump era

-

6 perfect gifts for travel lovers

6 perfect gifts for travel loversThe Week Recommends The best trip is the one that lives on and on

-

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?

How can you get the maximum Social Security retirement benefit?the explainer These steps can help boost the Social Security amount you receive

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

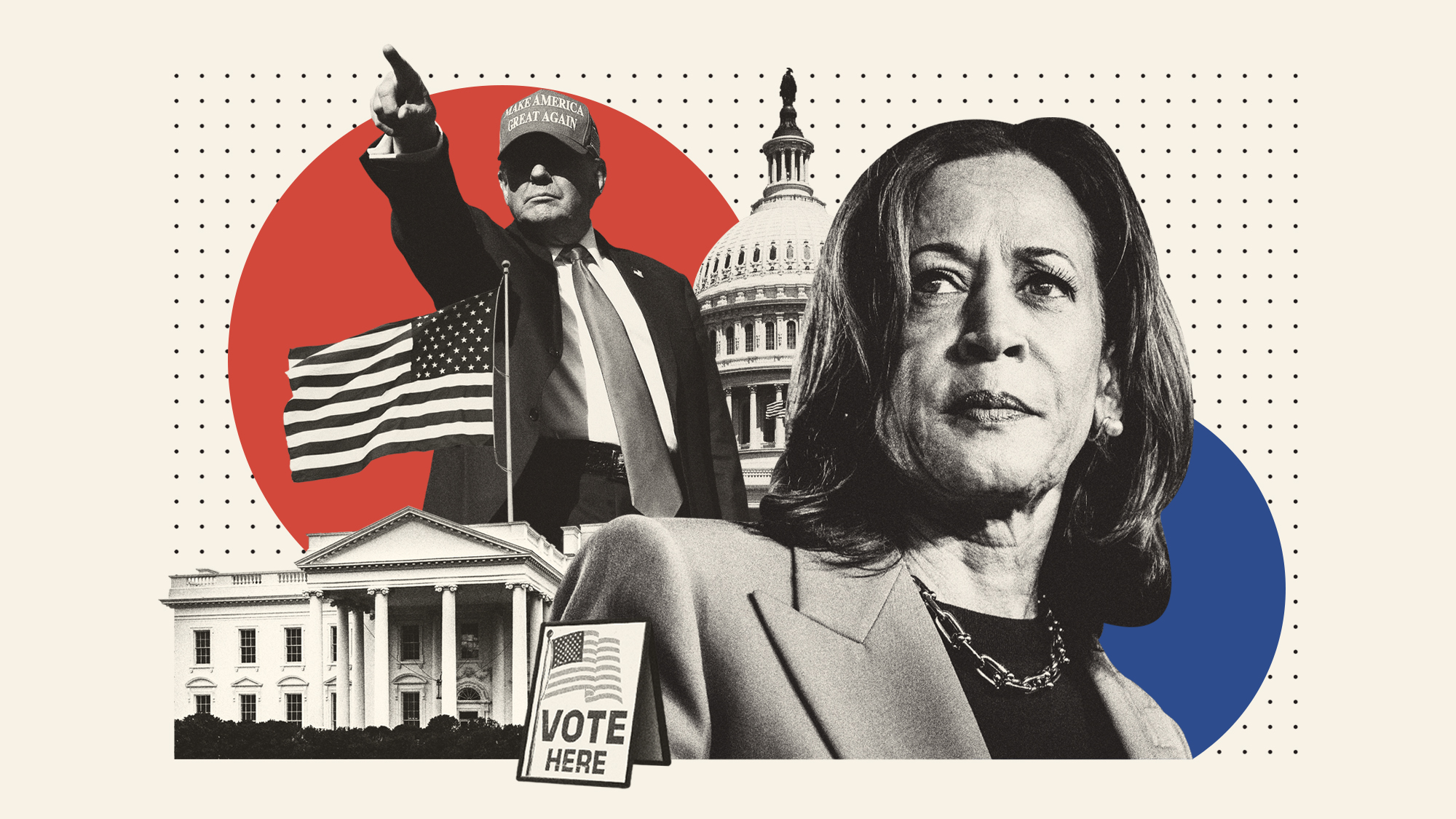

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?