The most clichéd talking point in foreign policy

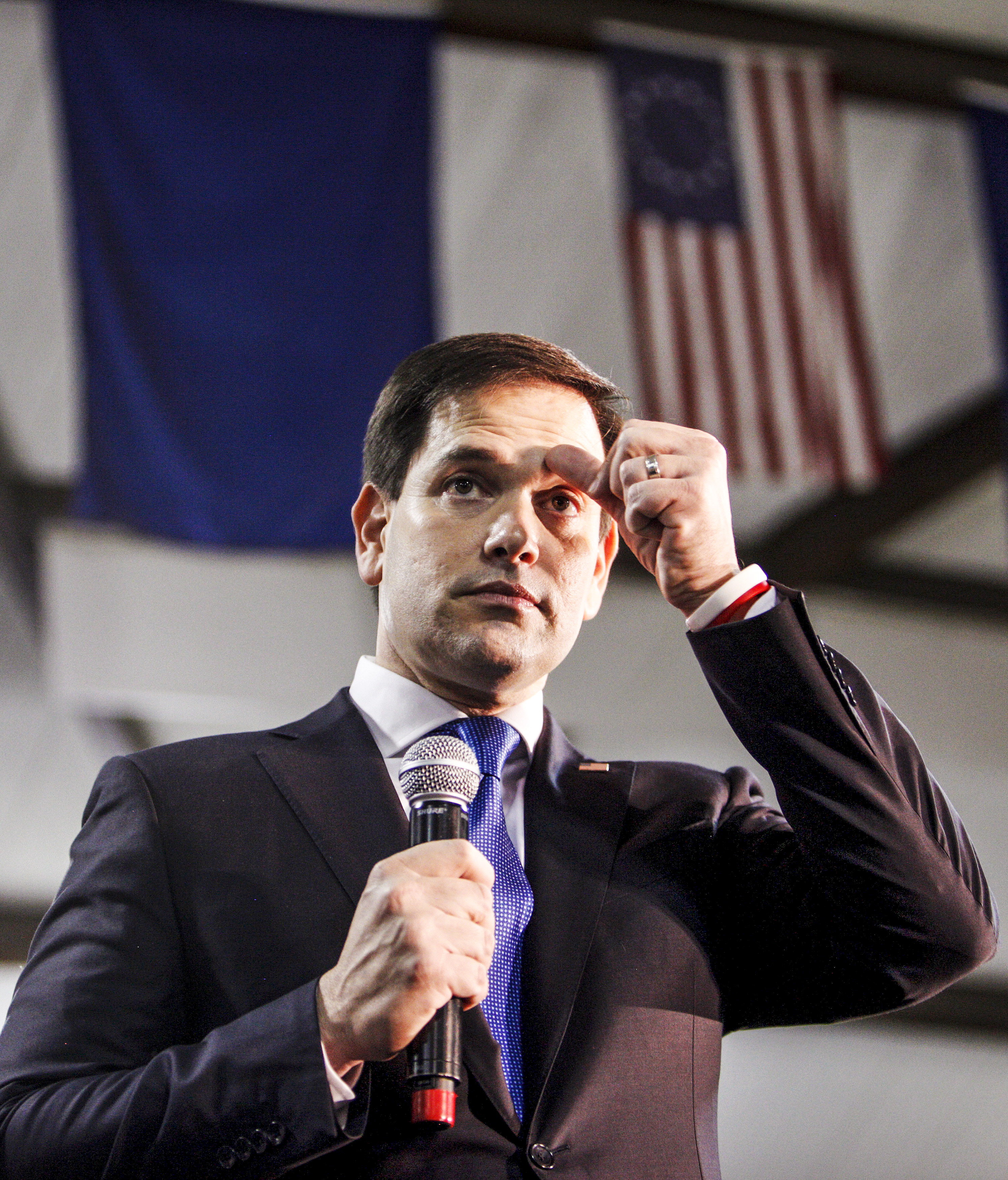

Marco Rubio really needs to stop saying 'working with'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The next president will find America in an awkward position. On one hand, we're the global hegemon, the indispensable nation, the world's policeman, the one to whom everyone turns to help solve problems from war to climate change. As such — and with the image of independence and self-reliance we cultivate as part of our national identity — we believe that we ought to be able to step in and with the right combination of wisdom and strength do whatever we set our minds to.

On the other hand, even the leaders of our more belligerent party are reluctant to do much alone in foreign policy, if that means things like a large-scale invasion of a country or two halfway around the world. As much as they offer tributes to American exceptionalism and decry Barack Obama as a weakling unwilling to let the bombs fly nearly often enough, when you listen closely to them you hear an awful lot of talk about how other countries are going to help us accomplish our goals. And that's often the hardest part.

As an example, take a recent interview Marco Rubio gave to the conservative Daily Caller about foreign policy. Like all Republicans, Rubio focuses in on Obama's alleged fecklessness, as contrasted with the strong leadership he would bring. Asked about how he would have handled the revolution in Libya, Rubio says he would have "decisively acted as opposed to dither, like the president did." And what does this decisive action involve? Not American troops, but some bombing (which the Obama administration did) and releasing money to the successor to Qaddafi's government. But here's the important part: "I would have engaged decisively. We would have ended that conflict quickly and we would have worked with the people that we were working with at the time to ensure that there was a stable national government that could have provided security and governance, as opposed to the chaos that ensued." So: decisive engagement! Which involves working with other people.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And what about Egypt, where a revolution was followed by an election where the wrong people won, and that was quickly followed by a military coup? "I would have worked with the Armed Forces of Egypt to ensure that there would have been a peaceful and sustainable transition."

"Working with" this group and that group sounds a lot like Rubio's plan to defeat ISIS, which involves building "a multinational coalition of countries willing to send troops into Iraq and Syria to aid local forces on the ground." That's a component of just about every presidential candidate's ISIS plan, both Republican and Democrat. In other words, it means getting somebody else to do what needs to be done.

There's nothing wrong with that, but it glosses over what's often the most difficult part of diplomacy: actually convincing other countries, each of whom have their own interests and their own internal political considerations, to do what we want them to do. How many times, when the discussion turns to foreign affairs, have you heard a candidate say, "I'll work with our allies" to accomplish some goal? But the complexity of that task is something that candidates almost never discuss. To listen to someone like Rubio, you'd think that "working with" some other country and getting them to do what we want is just a matter of pulling a switch, a decision that hasn't been made before now only because our current president is insufficiently decisive.

Even as Republicans pretend that the kind of diplomacy that produces unified action is easy to accomplish, they dismiss President Obama's actual diplomatic accomplishments as irrelevant, misguided, or weak. The nuclear agreement with Iran, for example, was a triumph of "working with" other countries. The administration managed not just to hammer out a deal with Iran, but to hold together the other parties to the agreement: Britain, France, Germany, the European Union, China, and Russia — not a group particularly inclined to stay in agreement on much of anything. The administration also got China to commit to lowering its carbon emissions, and signed a historic deal with nearly every country on earth toward the same goal at the recent climate talks in Paris.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Whatever you might think about the objectives of those agreements, their complexity and tenuousness right up until the eleventh hour (and beyond) demonstrate how silly it is to just say "I'll work with our allies to do this incredibly difficult thing, and that's how it'll get done."

It may be foolish to expect too much from campaign rhetoric. After all, on a whole range of subjects, candidates portray the process of governing and policy-making as easy and simple, where implacable opponents are won over with a sincere heart-to-heart, everyone's interests fall into alignment like tumblers in an opened lock, and unintended consequences are non-existent. That's what allows them to pretend they have all the answers, and our country and the world will be transformed by their inspiring leadership.

No candidate is going to say, "I'll do my best to solve this problem, but we're going to need help, and it's going to be awfully hard to get other countries to go along, so I don't know if we'll succeed." But it might be nice if every once in a while they acknowledged that nothing is as easy as we'd like it to be.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred