The left vs. the reality-based community

How a rash of left-wing intellectuals are imagining new worlds — and losing touch with ours

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It feels just like yesterday: the crisp fall day in 2004 when I met a friend for lunch who told me about a Ron Suskind article set to appear in the upcoming issue of The New York Times Magazine that included a blockbuster quote from an unnamed source in the Bush administration (later revealed to be Karl Rove).

Describing how the White House's approach to dealing with the world differed from the way journalists like Suskind operate, the aide suggested that the latter remained fixed on trying to understand the "reality-based community." The administration, by contrast, understood that "we're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality…. We're history's actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do."

Coming as it did roughly a year and a half after the invasion of Iraq, the military's failure to find stockpiles of WMD, and the rise of an insurgency that was plunging the country into chaos while the administration's spokespeople offered nothing but half-truths and happy-talk, the quote hit with the power of a revelation. The Bushies weren't merely disconnected from reality. They were proudly disconnected from it. They saw their indifference to reality as a virtue, a sign of their capacity to conjure new realities out of thin air by sheer, stubborn force of will.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Or so countless sensible centrists, smart liberals, and hard-headed leftists proclaimed over the next week or so in a slew of articles and blog posts mocking the breathtaking hubris of the quote. My own migration away from neoconservatism was already well underway by that point, but Suskind's article played a not-insignificant role in confirming my alienation from the right and my conviction that those on the left, whatever their other faults might be, were more fully committed to basing their policy proposals on an informed understanding of reality and its unavoidable complications and constraints.

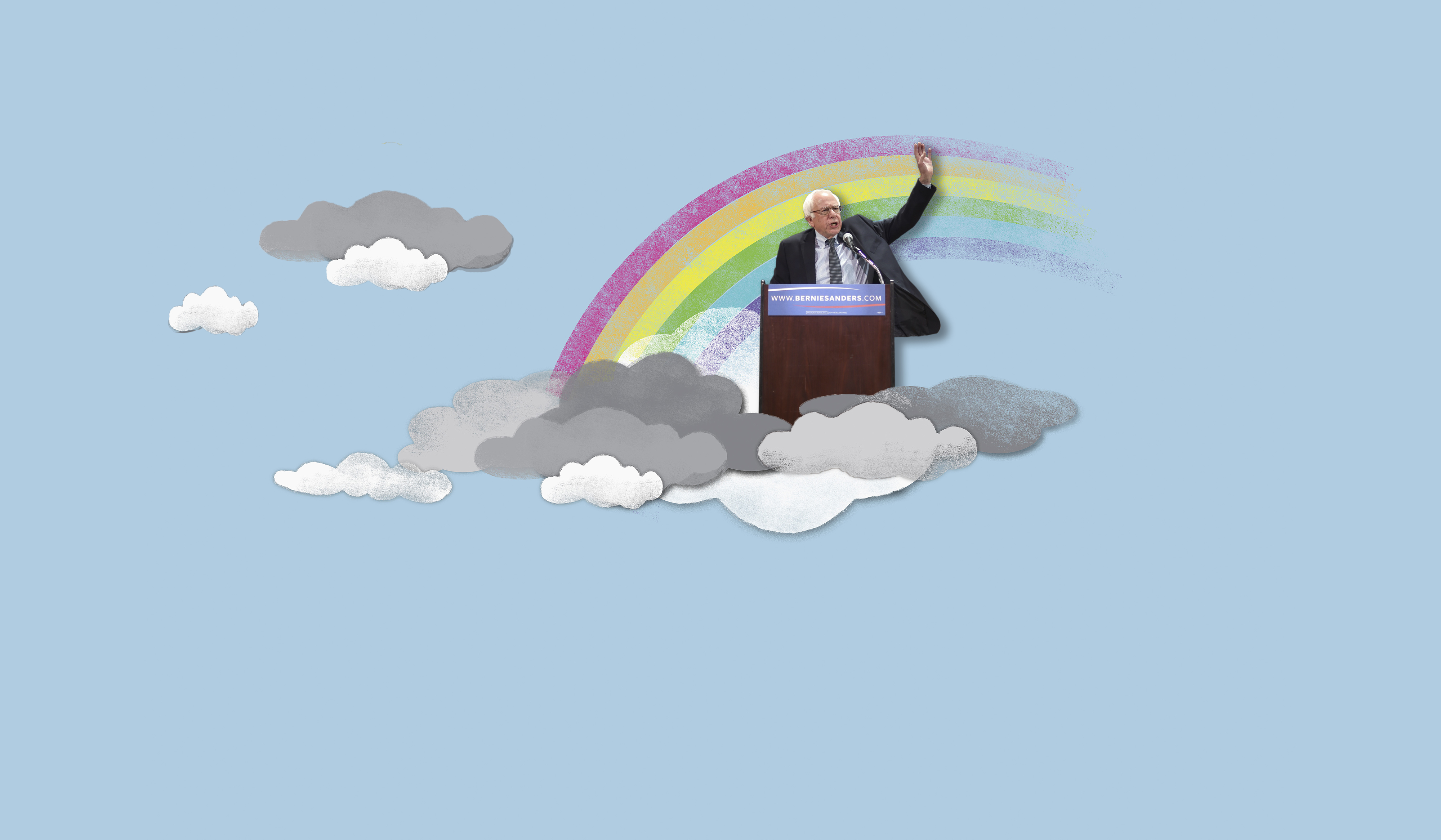

Fast-forward 11 years or so and I'm no longer so sure. From the high-flying socialist presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders to a pair of recent high-profile essays by leading intellectuals, the left appears just as ready and eager to cut itself off from the reality-based community as the Bush administration ever was.

The Sanders campaign has proposed well-meaning but impractical plans from day one: the endlessly repeated threats to "break up the banks," the promise of free college for all, the bid to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. But it's his latest plan — to scrap the nation's existing means of providing health insurance, including the hard-fought-for and still-polarizing ObamaCare reform, and replace it with a Medicare-for-all, single-payer system — that has launched Sanders into the realm of complete fantasy.

If the world could be started over from scratch, I think something like Sanders' proposal would be vastly more desirable than the wildly inefficient Rube Goldberg contraption that the U.S. is saddled with. But presidents don't get to start the world over from scratch. They start from where we are, not from where they wish we were — and in the world we inhabit, Sanders' proposal (which would be many times more disruptive and expensive than the Affordable Care Act) has close to a zero chance of passing Congress. Unless, of course, you believe the even more implausible scenario that a Sanders victory in November would also put the House of Representatives and the Senate in the hands of hard-left majorities.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is this indifference to political reality a defect or a plus? Left-wing commentator Corey Robin clearly thinks it's a virtue — and not just when it comes to presidential politics. In a provocative essay for The Chronicle of Higher Education, "How Intellectuals Create a Public," Robin argues that "the problem with our public intellectuals today is that they are writing for readers who already exist, as they exist," as opposed to "summoning" a new world, a new public, a new reality, into being.

Robin gives the example of author Cass Sunstein, castigating him for advocating a form of "libertarian paternalism," which aims to persuade the government to "nudge men and women to make better choices." This is a problem, for Robin, because it's a reform that "looks like the polity that already exists. Its setting is the regulatory state and capitalist economy we already have. Its ideology is the market fundamentalism we already pay obeisance to."

Sunstein compromises too much with reality, Robin believes — and so does Ta-Nehisi Coates in Between the World and Me, his widely acclaimed book about race in America. Sunstein and Coates "wind up in the same place," Robin insists, because they both presume that a politics of mass mobilization is futile. More than succumbing to mere pessimism, Coates is guilty of giving in to a quasi-theological form of "impossibilism." And that is unacceptable, not because Coates has based his conclusions on an inaccurate reading of American reality, but for the opposite reason — because he (like Sunstein) produces an "all too accurate reflection of the world we live in."

The intellectual isn't supposed to understand or interpret the world. He's supposed to change it.

Author Jedediah Purdy agrees. In "The New Nature," an essay published in Boston Review, Purdy proposes a radical rethinking of our assumptions about the natural world, humanity, and politics. It's a rich, dense piece of writing that readers would be well advised to work through and ponder on their own, along with the series of thoughtful responses to the argument and Purdy's spirited rejoinder.

What I'd like to highlight is the author's opening assertion that politics and economics have been "denaturalized" in our time, and that even nature itself is undergoing the same process. By this he means that all appeals to permanent, intrinsic truths or standards by parties involved in political, economic, or environmental debates have become unconvincing. Nothing is natural in the normative sense — no political or economic arrangement, and not even any specific construal of the natural world and its meanings.

All such appeals to nature are in fact conventional, artificial constructs of the human mind imposed upon the world. And Purdy sees this as a wonderful opportunity, because it holds out the possibility of a collective "world-shaping project" that would bring about a radical democratization of politics and economics, and of the relation of both to the natural world.

The problem with this way of describing the world is not merely that it's wrong. (As long as human beings have physical bodies that can thrive, be injured, and die, and as long as they live out their lives in a physical world that obeys natural laws disclosed by science, politics and economics will be hemmed in by constraints and obstacles that stand in the way of any number of potential "world-shaping projects.")

The even bigger problem with Purdy's account of things is that it renders political evaluation and judgment impossible. As Will Wilkinson writes in a brilliant critique of the essay, "Appeals to value only make sense — only count as considerations for or against anything — against a background of belief about how things really are. If our best ideas about the way the world works can't put a boundary around political contestation, then leaving the lead in Flint's drinking water makes as much sense as taking it out."

Political thinking and acting cuts itself off from reality at its peril.

By now that's something I suspect even Karl Rove would concede.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trends

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trendsthe week recommends It’s hojicha vs. matcha, plus a whole lot more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred