10 commonly abused psychology words — and what they really mean

Many of the psychology terms we use in causal conversation don't mean what we think they do

If you're like many people, you can be a little OCD about language, but at the same time you can go ADHD and lose the thread and use some words loosely. Like you're kinda bipolar or schizophrenic about it, ya know, and maybe you get paranoid that someone's gonna go psycho on you about it.

Well, maybe it's time to know what all these mental-health-related words are really supposed to mean, and what the disorders they name really involve.

1. OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Many people use OCD to mean "a desire to be tidy and keep things in order." Alphabetizing your bookshelf? "My OCD kicked in." Tupperware always neatly stacked? "I'm a little OCD about my kitchen." One tile out of place on a floor? "This will drive people with OCD crazy."

But OCD is not just a desire for order. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), says that OCD obsessions are "intrusive and unwanted" and its compulsions are "aimed at preventing or reducing anxiety or distress, or preventing some dreaded event or situation" but "are not connected in a realistic way" with what they're supposed to prevent "or are clearly excessive." They take up a lot of time or interfere badly with life.

DSM-5 distinguishes between OCD and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder, however. OCPD involves extreme versions of traits you probably recognize in some people — extreme preoccupation with rules and order "to the extent that the major point of the activity is lost," "perfectionism that interferes with task completion," excessive devotion to work, extreme inflexibility, miserliness, and what we often call "control-freak" behavior. If you know someone who is so stuck on getting something exactly right that it never gets done or other things get ruined entirely, or someone who insists on rules or moral principles to the point of hurtfulness or destructiveness, that person may have Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder. A key point is that it's a personality disorder. People with personality disorders are generally difficult to deal with, but they see other people as the problem.

If you just like to have everything tidy, you probably don't have OCPD, and you certainly don't have OCD.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

2. ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder)

Some people use ADHD loosely to mean "can't pay attention or concentrate." Others scoff at it as a way of prescribing pills to kids who just eat too much sugar. But it's a clinical condition, which means the real thing makes life a lot more difficult than it should be.

DSM-5 has a list of nine symptoms of inattentiveness and nine of hyperactivity and impulsivity. To qualify for diagnosis the person has to have at least six of one, six of the other, or six of each, "that have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that negatively impacts directly on social and academic/occupational activities." Also, several of the symptoms have to have been present before age 12, and several have to be present in two or more settings.

ADHD is a comparatively common diagnosis, and there are probably many mild cases of it that are never diagnosed. But getting bored when doing something most people find boring is — to use the terminology — not diagnostic.

3. Narcissist

It's common to use "narcissist" to mean "vain" or "egomaniacal" or "self-obsessed:" "OMG millennials are such narcissists, always taking selfies!" "Aw, that politician is a narcissist, always taking credit for everything and needing his ego stroked."

Much of this is just common reference to the mythological figure Narcissus, who spent so much time looking at his own reflection that he died. But there is a clinical diagnosis, Narcissistic Personality Disorder, defined by DSM-5 as "a pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts." You need at least five of nine characteristics to be diagnosed, including arrogance, exploitativeness, and a sense of entitlement.

There are public figures who are thought by many to have these characteristics, but don't expect them ever to go in and be clinically assessed. Being self-centered isn't automatically NPD, and liking to take lots of selfies isn't diagnostic. Also, "Narcissistic traits may be particularly common in adolescents and do not necessarily indicate that the person will go on to have narcissistic personality disorder."

4. Manic-depressive/Bipolar

Many people seem to think bipolar disorder is having "mood swings" or "up days and down days." Jimi Hendrix's song "Manic Depression" is about romantic uncertainty and its attendant emotional ups and downs, not quite something that could hospitalize you.

"Manic-depressive" and "manic depression" aren't technical terms anymore. The DSM-5 term is Bipolar Disorder, and it's a whole spectrum of disorders, all characterized by both major depressive episodes and manic episodes. And they don't last just a few hours or a day or two. Manic episodes involve "abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and persistently increased or goal-directed activity or energy, lasting at least one week;" this tends to include such things as extreme talkativeness, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, and risky behavior. Depressive episodes are not necessarily exactly the opposite in every way — the person may be agitated rather than lethargic — but they are generally the opposite, and strongly so.

Manic and depressive episodes resemble the happy and sad moods most of us have in about the same way an aircraft carrier resembles a yacht.

5. Schizophrenia

Some people think schizophrenia is multiple personality disorder (now called Dissociative Identity Disorder) — when a person flips between different distinct personalities. But while the term schizophrenia comes from Greek for "split mind," what it means is that different functions of the mind are dissociated from one another.

There is quite a lot of variation in the symptoms of schizophrenia, but in order for it to be diagnosed according to the DSM-5, a person must have delusions, hallucinations, and/or incoherent or frequently derailed speech, and may be catatonic, grossly disorganized, or lacking in emotional expression or volition. The symptoms have to last a long time: at least a month in full severity, and six months for associated signs.

While many people have ideas from TV and movies of people with schizophrenia as "psycho killers," the DSM-5 points out that "the vast majority of people with schizophrenia are not aggressive and are more frequently victimized than are people in the general population."

6. Paranoid

"Paranoid" is often used conversationally to mean just "worried" or "self-conscious": "I'm paranoid that I have something stuck in my teeth;" "I'm paranoid when someone asks me to hold their baby, like that I'll drop it or it'll poop on me;" "I'm always paranoid at border crossings." This has little to do with the clinical version.

Classically, "paranoia" was the original Greek catch-all term for mental illness, from para "beside" and nous "mind" — in other words, out of your mind. More recently it's become a more specific diagnosis. Paranoid Personality Disorder, in the DSM-5 sense, means "pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others such that their motives are interpreted as malevolent." This doesn't mean worrying too much that things will turn out badly. It means taking compliments as underhanded criticisms, viewing honest mistakes as maliciousness, and bearing grudges for a long time. In short, people with Paranoid Personality Disorder don't just worry that people are out to get them; they're sure that they are, and they despise them for it.

7. Psychotic

"Psychotic" is, in popular use, like an amped-up version of "crazy." People use it to describe people whose behavior or political beliefs seem wildly irrational. "Psychotic" in the DSM-5 sense, on the other hand, is a broad term encompassing a number of different disorders, including schizophrenia. What they have in common are one or more of "delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia), and negative symptoms." What they mean by "negative symptoms" is feeling less, saying less, doing less, and wanting to do less than is considered normal.

In short, the difference between what many people use "psychotic" to mean and what it officially means is like the difference between "I died laughing" and a coroner's report.

8. Psychopath

"Psychopath" is popularly used to mean someone who is dangerous and lacking in shame, remorse, or an appreciation of consequences. Various disliked public figures regularly get called psychopaths.

The DSM-5 doesn't use the term "psychopath" to refer to people. It avoids essentializing disorders: A person is not a "schizophrenic" but an "individual with schizophrenia," and not an "alcoholic" but an "individual with alcohol use disorder." But it uses the term "psychopathology" quite a lot. That's because it's from Greek roots meaning "mental illness." So it encompasses pretty much everything in the manual, not just conditions that involve remorseless cruelty.

In other words, "psychopath" isn't a clinical term, and if it were one, we'd still be using it wrong. The way most people use it is just another way of saying "nasty crazy," which is not clinical or, for that matter, particularly useful.

9. Insane

The word "insane" is not used in the DSM-5 even once. Yes, it used to be used officially. It comes from Latin meaning "unhealthy," and at one time it was a dry clinical term. But its use got polluted by popular misperceptions and prejudices. Sort of like "psychopath" and, for that matter, a number of other terms for mental illnesses.

10. Crazy

Unlike "insane," the word "crazy" is actually used in the DSM-5. Not as a diagnostic or clinical term, of course! It's used to describe something that people with some kinds of anxieties are afraid of becoming or being seen as. A person with social anxiety is worried about being judged as "anxious, weak, crazy, stupid, boring, intimidating, dirty, or unlikable;" a symptom of a panic attack is "fear of ‘going crazy'" — the manual explains that "'fear of going crazy' is a colloquialism often used by individuals with panic attacks and is not intended as a pejorative or diagnostic term."

Because of course that's how people in general use it: pejoratively. "Crazy" comes from the verb "craze," which means "crack up" (literally); crazed glass has a lot of small cracks. So a crazy person is, metaphorically, seen as all cracked up. We have in our culture a long history of derisive use of terms for mental diseases, just as we do for some kinds of physical diseases and disabilities: "leper," "cripple." A word like "crazy" shows us how we tend to respond to mental illness: with fear, meanness, or a desire to laugh it off.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

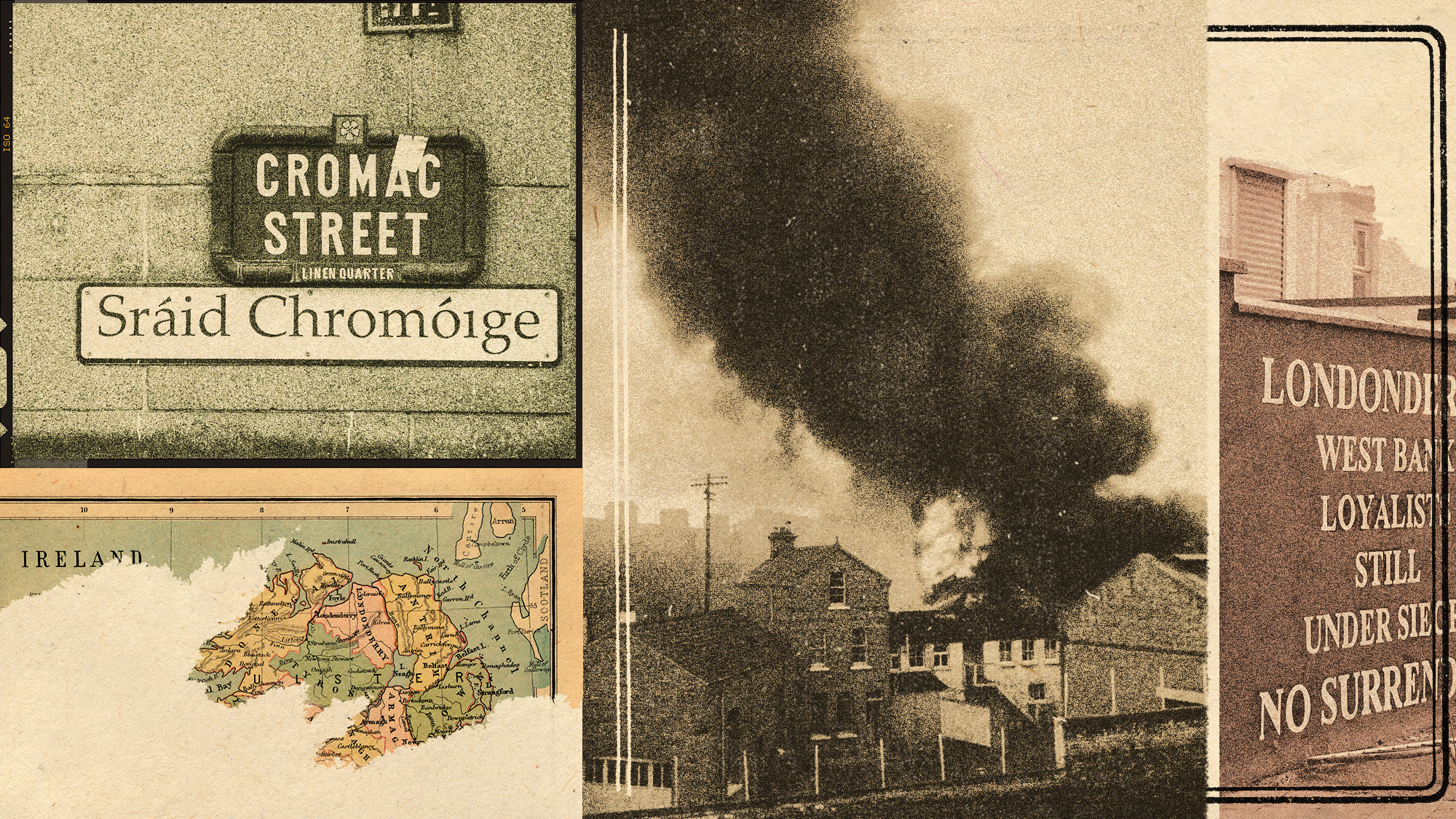

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

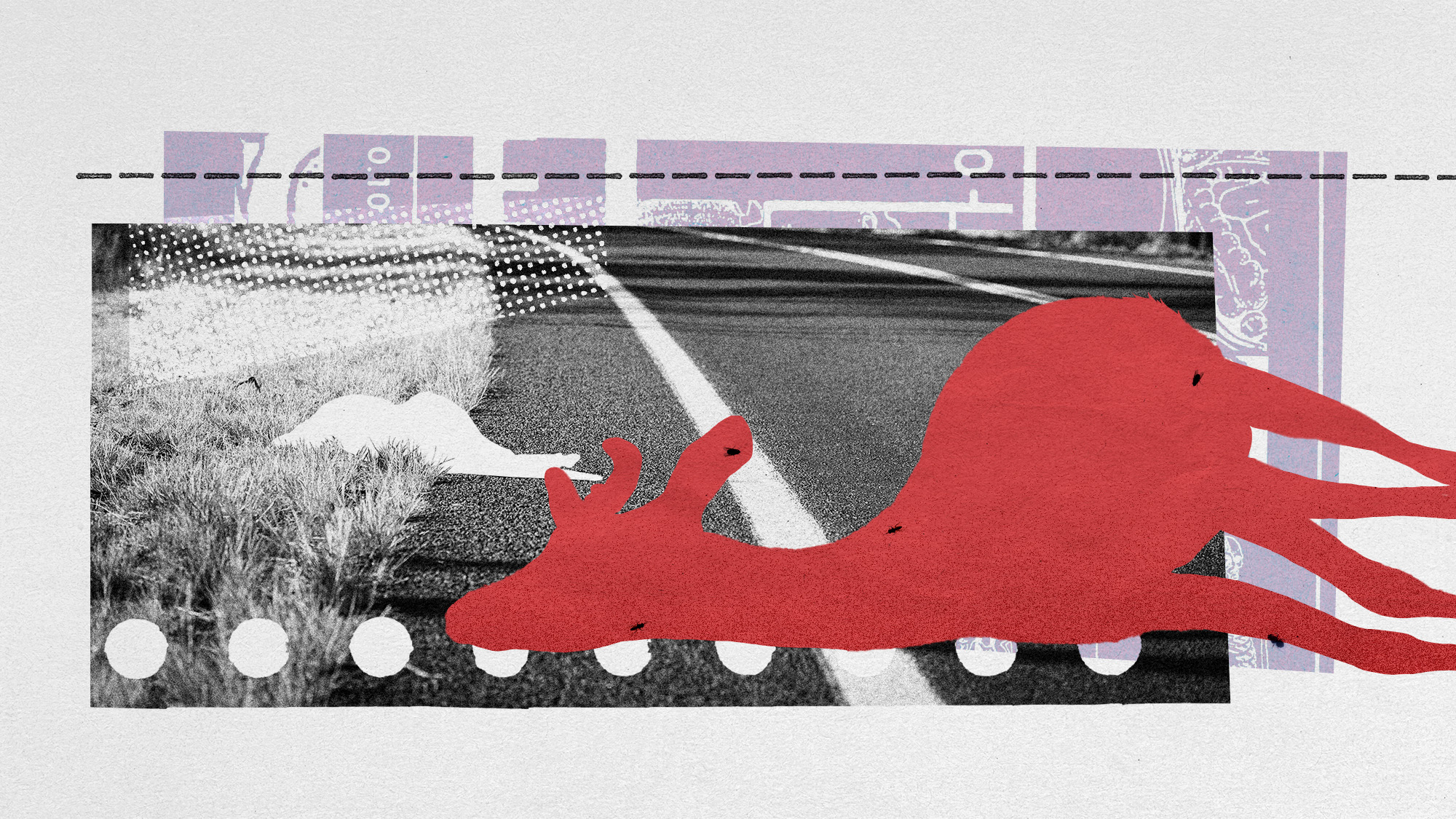

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them