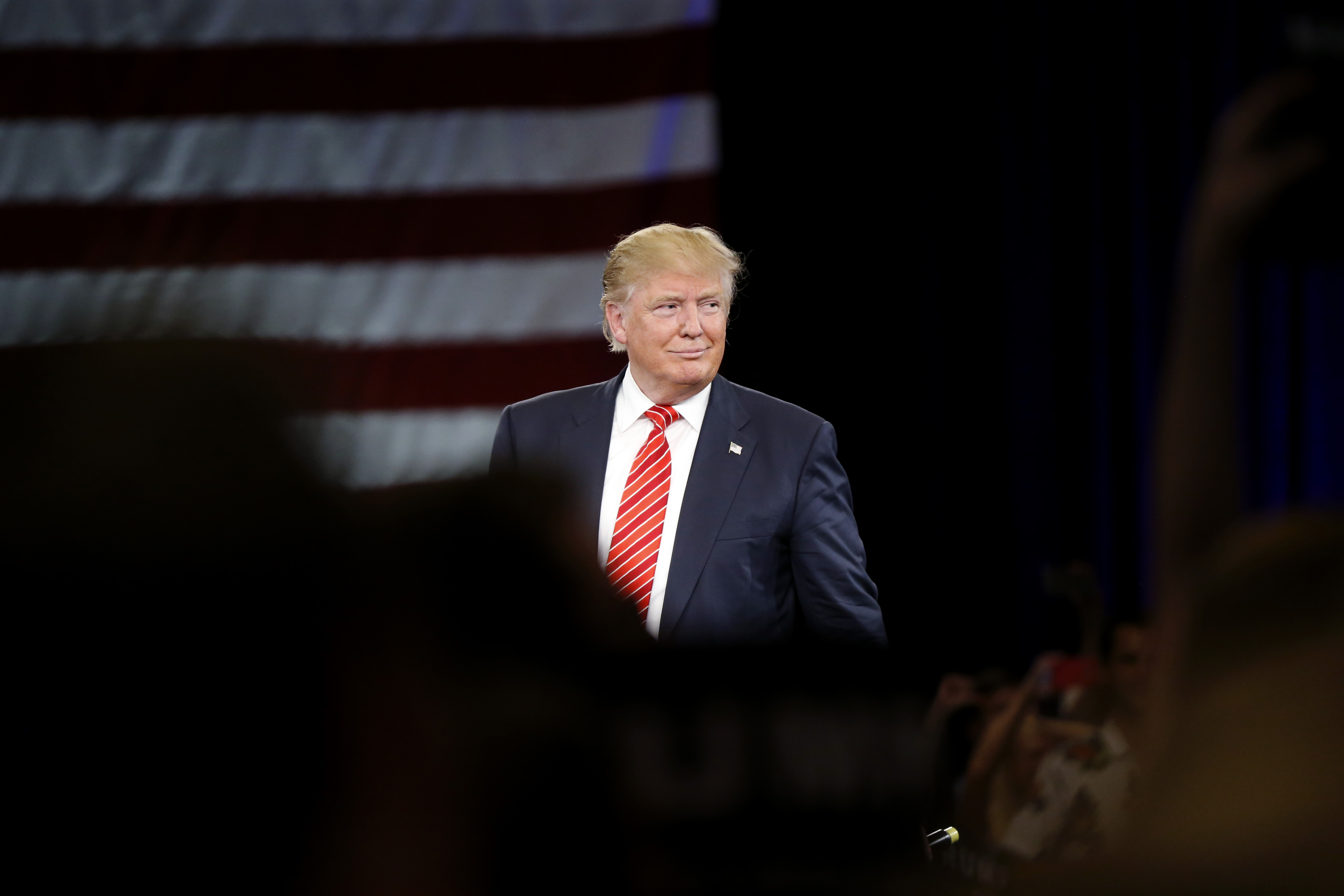

American liberals have a corrosive illiberalism problem. And Donald Trump is exploiting it.

In the age of Trump, we need true liberalism more than ever

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The provocation arrived, as it so often does these days, via Twitter.

The link leads to a Los Angeles Times article about how the University of California system is "proposing to include 'anti-Zionism' as a form of discrimination that is unacceptable on campus." Once I read the article, the provocative intent of the tweet became clear: Its author was being ironic. He didn't at all expect loud condemnations from defenders of free speech, including me. He expected us to display rank hypocrisy.

I strongly criticized the protesters whose actions led to the cancelation of Donald Trump's rally in Chicago last Friday evening. But surely I would remain silent about the prospect of institutions of higher learning curtailing the free-speech rights of vociferous critics of the Jewish State, many of whom (at least on college campuses) are on the left.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Because, the tweeter assumes, I'm not really a defender of free speech. I'm actually inclined toward a pernicious double standard — defending free speech for those I agree with while displaying indifference when those on the other side are silenced.

That sounds bad. Good thing it isn't true.

I'm a proud liberal, and a consistent one. I strongly oppose Donald Trump, the style of politics he practices, and the kind of policies he promises. Yet his admirers have every right to assemble to hear him speak at campaign rallies. The effort to stir up dissension and violence at those rallies, as happened in Chicago, is not only tactically counter-productive. It's also illiberal in aim and intent.

The same is true, on all counts, of efforts to get anti-Zionism declared unacceptable in the University of California system. I'm offended by anti-Zionism in most of its forms. Before the modern nation of Israel existed, one could debate whether an ingathering of the Jewish people in their ancestral homeland was a good idea. But with Israel's founding, that debate became as morally obscene as mulling over whether France should disband itself as a nation, scattering French men and women across the globe, or subjecting them to rule by a virulently anti-French majority within the country.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet those who wish to make the anti-Zionist argument should be allowed to do so — provided that those who disagree are also free to make counter-arguments and even to describe the anti-Zionist position as morally obscene (as I just did). This should be true everywhere, but especially on university campuses, which exist in part to foster, protect, and encourage free-wheeling argument and debate.

I hold these views without hesitation and uphold them in my writing as consistently as I can. That's because I consider them essential for the healthy functioning of a liberal society — at all times, but perhaps now more than ever.

We're living through a sharply illiberal moment in America. Following through and expanding on the logic of anti-discrimination law, which seeks to protect distinct classes of citizens from unequal treatment in public accommodations, the activist left increasingly uses a mixture of bureaucratic regulations, protest, and public disruption to get an ever-growing list of topics relegated to the category of the undiscussable. These topics must not be raised because talking about them produces offense, which amounts to a form of discrimination. Those in the University of California system who are trying to rule anti-Zionism out of bounds are merely expanding this logic one further step, to get Zionists added to the list of groups officially protected from offense.

An alarmingly large swath of the right, meanwhile, has embraced an illiberalism of its own, with the shockingly successful presidential campaign of Donald Trump its boldest expression yet. A lot has been written about the economic sources of Trump's rise, especially the decline and frustrations of the white working class. But the visceral hostility of many Trump supporters to "political correctness" is also a significant factor. Trump has openly attacked Mexican immigrants, Muslims, and other groups during his campaign, and his admirers treat these attacks as a welcome sign that as president he wouldn't allow himself to be pushed around by those who would deny his right to think and say whatever he wants.

But of course, Trump's illiberalism goes far beyond language. He demonizes undocumented immigrants and Muslims in order to lay the groundwork for blatantly illiberal government policies: the rounding up and forcible deportation of the former and the (temporary) banning of the latter from entering the United States.

It is these types of proposals that inspire protesters to disrupt and shut down Trump campaign events. In that way, illiberalism feeds off of and provokes further waves of illiberalism in endless, escalating cycles.

The liberal path shows how to break the pattern.

When a professor or student — or a presidential candidate — makes a claim or an argument that you dislike, disagree with, or even find offensive, the proper response isn't to shut him up or shut him down. It certainly shouldn't involve making insults or threats, which has become the norm in the pervasively illiberal world of social media.

Instead of seeking to drown out or silence views you reject, it's far better to respond with an argument on the other side. Show why you think the claim or argument is wrong. Dismantle it using reason and rhetoric, not force (whether physical or verbal).

What makes the contrary approach illiberal is that it treats one's own position as unambiguously true and those held by others as unambiguously wrong. And the wrongness isn't held to be an innocent mistake. It's treated as an offense, as something corrosive and insidious that can harm, offend, and corrupt. The error must therefore be given no rights. It must be stamped out, suppressed, banned.

But of course those holding the offending view often feel exactly the same way about their own positions and the unambiguous wrongness of views held by others.

A world without liberalism would be a world of zero-sum competition in which compromise and persuasion are impossible, in which metaphorical or literal force inevitably prevail, and each group either wins or loses everything in the battle.

The alternative is to look at the world through a liberal lens, practicing the art of conciliation that sustains a civil society (and keeps it from devolving into a civil war prosecuted by other means). Liberals in this temperamental sense combine any number of possible ideological commitments with an awareness that people of good will often disagree about what is right and true, and that reasoning together is the surest (and perhaps only) path to achieving, not universal agreement, but a modicum of understanding and compromise.

As a wise man once wrote, "To realize the relative validity of one's convictions and yet stand for them unflinchingly is what distinguishes a civilized man from a barbarian."

Whether at the University of California or on the presidential campaign trail, America in 2016 could use a little more civilization and a lot less barbarism.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred