How Hillary Clinton uttered the most radical truth of the 2016 election

When was the last time you heard a politician say that transactional politics can be worthwhile?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

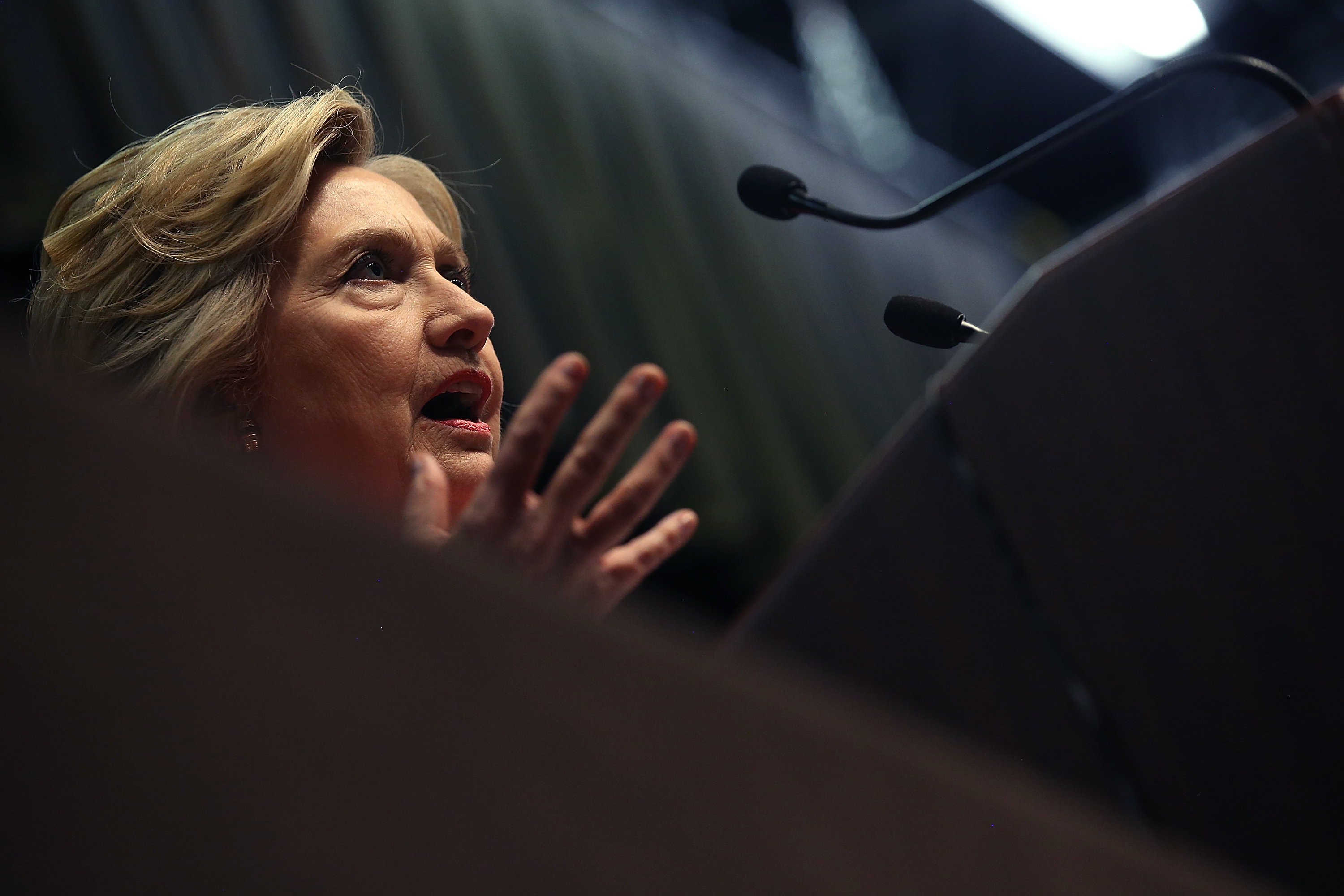

We don't usually think of Hillary Clinton as a candidate who goes around saying things that are surprisingly candid; she's the most careful of politicians, making up for her lack of improvisational political talent with diligent preparation and cautiousness. But a few days ago, Clinton said something much more radically honest than any of the sewage that spews out of Donald Trump's mouth when he's supposedly "telling it like it is," or even any of Bernie Sanders' critiques of the way our system operates. It was only because it sounded mundane that it was barely noticed.

Speaking to the New York Daily News editorial board, Clinton was asked a question about the Obama administration's 2009 stimulus package, with the questioner saying that much of the money "was divided up politically." Clinton responded, "Well, look. Politics has to play some role in this. Let's not forget we do have to play some role. I got to get it passed through Congress. And I think I'm well-prepared to do that. I was telling you about Buffalo. I got $20 million. Now I got that because it was political. But it worked. And it has created this amazing medical complex."

Clinton may not have thought at that moment that she was speaking an unutterable truth, but she was. When was the last time you heard a politician say that there's something worthwhile about politics?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most of the time, people who have devoted their lives to politics describe it as something unseemly, repugnant, even vile. They paint themselves as missionaries from the real world, nobly attempting to bring things like "common sense" to the Gomorrah of Washington, D.C., a place they can't stand to set foot in (no matter how hard they're trying to get us to send them there or let them stay). Any process, decision, or motivation involved in the operation of government can be dismissed with a sneer by saying it's "political." Worrying about "politics" is only for my opponents and other selfish, despicable characters; I'm just trying to do the right thing for the American people. The last thing I'd ever want is to become a part of the political system; I'm making the supreme sacrifice of getting elected only so I can "change the way they do business in Washington."

That kind of rhetoric has been a mainstay of our debates for a long time, but I can't recall a time when there was so much contempt for the very idea of politics. Republicans in particular are desperate for outsiders who can claim to be unsullied by the political process. This election comes at the end of a long period in which even the most long-serving politicians courted the Tea Party movement and claimed to share its disdain for the system, the establishment, the old guard, the way things have always been done.

Some might say, "Well just look at what Washington has become! Endless bickering, intractable partisanship, government shutdown crises, potential debt defaults. They can't get anything done!" Which is true. But it's also true that all those things are more a product of the contempt for politics than they are its source. The system has broken down precisely because it's been captured by "outsiders" who don't give a damn about making it work.

To a degree, those tea partiers are just an exaggerated version of the Republicans who came before; it's been said that Republicans claim that government can't do anything right, then when they get power they set out to prove their claim true. No one in Washington is more committed to gumming up the works than those who proclaim most loudly that they aren't actually politicians and they can't wait to get out of Congress.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But it isn't always partisan. Again and again we've seen how reforms that grow out of a disgust with politics end up making the system work less effectively. For instance, a few years ago, Republicans and Democrats decided together to end earmarks, the legislative provisions targeted to specific projects in members' districts. It came from a perfectly reasonable impulse — if a member can't request and receive an appropriation for her constituents, then there will be no more repeats of the "bridge to nowhere" and the taxpayers' money will be spent more wisely.

But it turned out that earmarks — which never made up more than a tiny proportion of the budget anyway — served a vital purpose. They greased the wheels of government by allowing congressional leaders to bring wavering members on board to pass budgets and move other vital legislation, by giving them a new road or park or hospital wing in their district. For a relatively modest cost, one could keep the engine moving forward (and plenty of earmarked projects were perfectly worthy). Without any carrots to provide members, legislating becomes less transactional — less "political" — and more ideological.

Or consider term limits. The idea is that legislators get too entrenched in the old ways of doing things and too concerned with holding on to their power, so what you need is regular injections of new blood. But states that passed term limits for their legislatures found they did more harm than good by depriving the legislature of experience and accountability. As Governing magazine wrote, "Numerous studies have linked [term limit] laws to poor fiscal health, arguing they actually lead to less sound policies because legislators won't have to face voter wrath later on. Others studies have found that term limits give interest groups and career lobbyists the upper hand because they've spent far more time in state capitols than the lawmakers themselves."

That isn't to say that every reform we might put under the "anti-politics" heading is a bad idea with unintended consequences. For instance, there's nothing good about politicians' unceasing need to raise money, and the few states that have instituted "clean election" systems for their state legislatures (where candidates choose to accept only small donations and get ample public funds in exchange) have found a good deal of success, with legislators freed to concentrate on policymaking. But we should remember that though politics is messy and sometimes even distasteful, you can't have a functioning government — or a functioning society — without it. Of course we should always try to make our system as clean and high-minded as we can. But it's things like corruption, waste, and inefficiency that are the real enemies, not politics itself.

I don't know if Hillary Clinton would say the same thing again if she had the chance to think about it. Perhaps she would — she is, after all, the candidate who sells herself on her mastery of the system and her belief in incremental change. But unfortunately, you can seldom go wrong by saying that unlike every other politician, you'd never stoop so low as to engage in politics.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

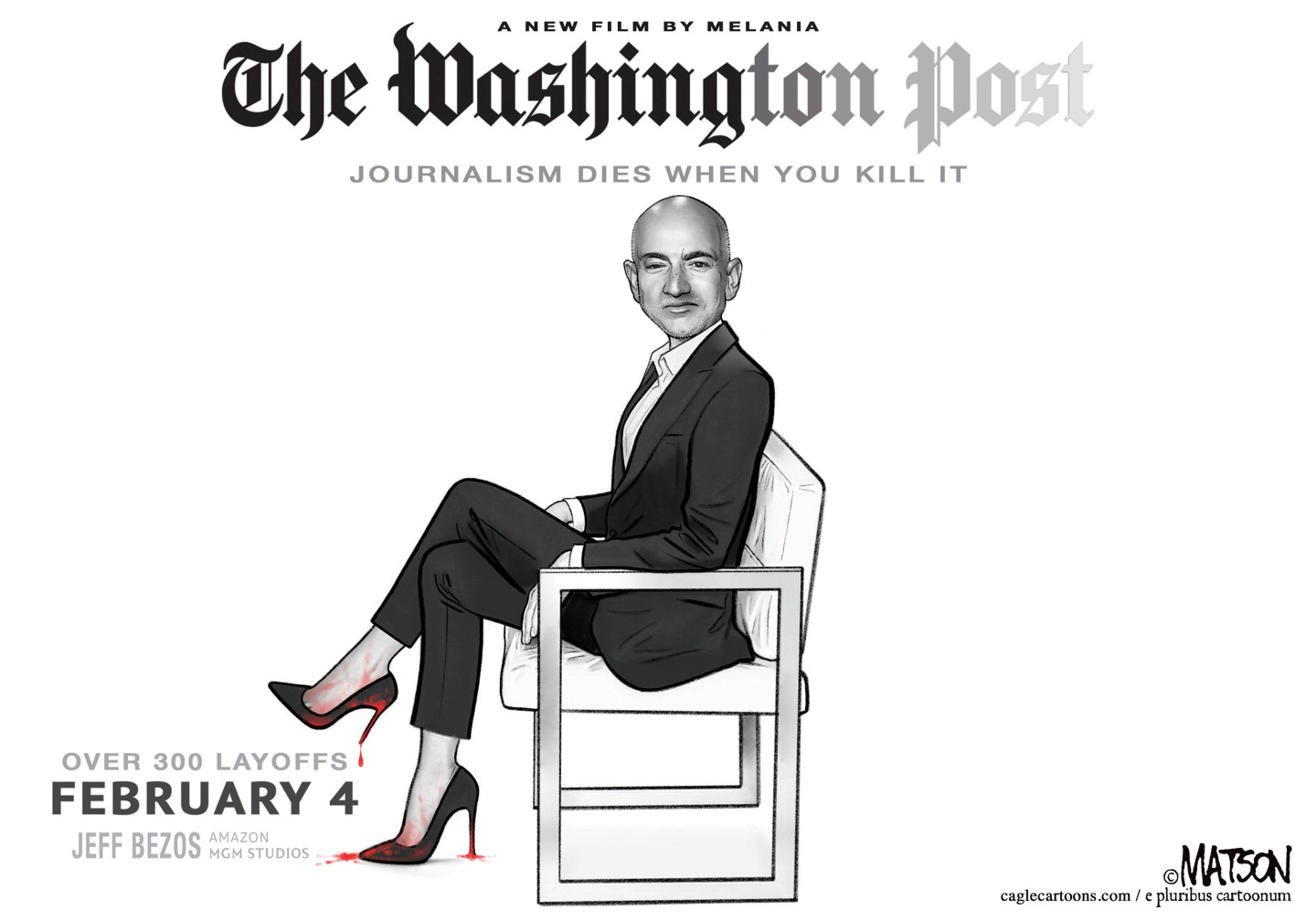

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred