The contemptuous certainty of Barack Obama

The president has all but wrecked Democrats' credibility on foreign policy. Can Hillary Clinton salvage it?

There's nothing like a good end-of-administration media kerfuffle to take our minds off the great gong show of Election 2016 — and Ben Rhodes, President Obama's very grumpy, very self-righteous, and very frank deputy national security adviser delivered.

Insiders freaked that Rhodes told The New York Times Magazine that the administration pushed narratives on favorite media outlets, especially on the Iran deal. Critics groaned when he explained the milieu of the foreign policy world by invoking novelist Don DeLillo, a symbol of the established snob who styles himself a counter-establishmentarian sage. Eyeballs popped when Rhodes concluded the country's twenty-something reporters "literally know nothing."

You may not want to care about this game of elite inside baseball, but you should. It's a sharp warning about the world we're going to face after November's election. The Rhodes affair ensures that President Obama's most immediate legacy on foreign policy will be to have trashed the White House's credibility for all too meager gain. And while Team Obama seems to think they'll have the verdict of history on their side, they've created a huge problem for Hillary Clinton.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As if she didn't already have enough to do, Clinton must now focus precious energy on proving she can be trusted to un-corrupt the foreign policy decision-making process if she wins the White House. Not only do influential Democrats and a nervous, increasingly isolationist base need to hear this — those anti-Trump Republicans Clinton wants to woo do too.

How did it come to this? It appears that President Obama decided very early on that the Beltway's foreign policy establishment was not to be trusted to do the right thing — or even to think independently about what the right thing might be. To be sure, its track record left something to be desired. Obama inherited a geostrategic mess, a weakened country that had lost the initiative, and a string of difficult choices that had to be made under intense time pressure.

His first-term choices reflected that. He resolved to buy time on Iran by opting against military action, to buy time on Afghanistan by scoring a symbolic capstone win with the killing of Osama bin Laden, and to buy time on Iraq by giving Baghdad enough rope to gradually hang itself. In the White House's judgment, at least, it all fell under the rubric of "don't do stupid stuff" — the motto Obama rather snidely shared to signal just what he thought of the establishmentarians he increasingly froze out of the policymaking process.

But if Obama's close-knit crew of foreign policy outsiders deserved some credit for gaining the U.S. some desperately needed breathing room, its inexperience and misplaced idealism caused that precious time and energy to be squandered in a string of second-term fiascos. From Libya to Syria to Yemen to ISIS to Europe to Russia and beyond, Obama's personal lieutenants made choices that repeatedly led to "stupid stuff" — and worse. And worst of all, if they've been at all humbled by the experience, they've been loath to show it — or act like it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's why Rhodes' forthright contemptuousness made such an outsized splash. It merely put a spotlight on just how deeply in denial the president's tiny circle of neophyte advisors have become about their self-imposed reversal of fortune. This crew, of which Rhodes is just one member, simply does not care that it has torched its reputation with a broad swath of D.C.'s most reasonable and experienced foreign policy makers and analysts.

This goes far beyond the crew's parlous record with Obama's defense secretaries. (All three of Ash Carter's predecessors — Bob Gates, Leon Panetta, and Chuck Hagel — left the administration throwing up their hands in disgust.) Even the plugged-in "less-than-hawkish types" who vented to The Washington Post's Dan Drezner were "pretty infuriated by the fact that Rhodes sounds so sure that he has gotten foreign policy right. At a minimum," Drezner explained, "anyone with a hand in running American foreign policy while the Russian 'reset' collapsed, the Arab spring curdled, and Syria, Libya, and Yemen disintegrated might consider whether such self-certainty is truly deserved." To a key set of mainliners, Democrats included, whom Clinton will need to rally, Rhodes' words came off as a bizarre and unseemly end zone dance on behalf of an inner circle whose deep disrespect for the foreign policy establishment is an open secret in Washington.

For the Beltway's foreign policy lifers, the attitude problems that have corrupted the policymaking process in the Obama White House offer a grim premonition of life under a Trump administration. But Team Clinton, itself notoriously insulated and ingrown (as Sid Blumenthal's Benghazi-era emails reminded D.C.), will not be playing to its strengths in trying to prove it will restore the warmth, competence, and trust that the president took away — at a moment, next year, when salvaging America's role in the world will be challenge enough.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

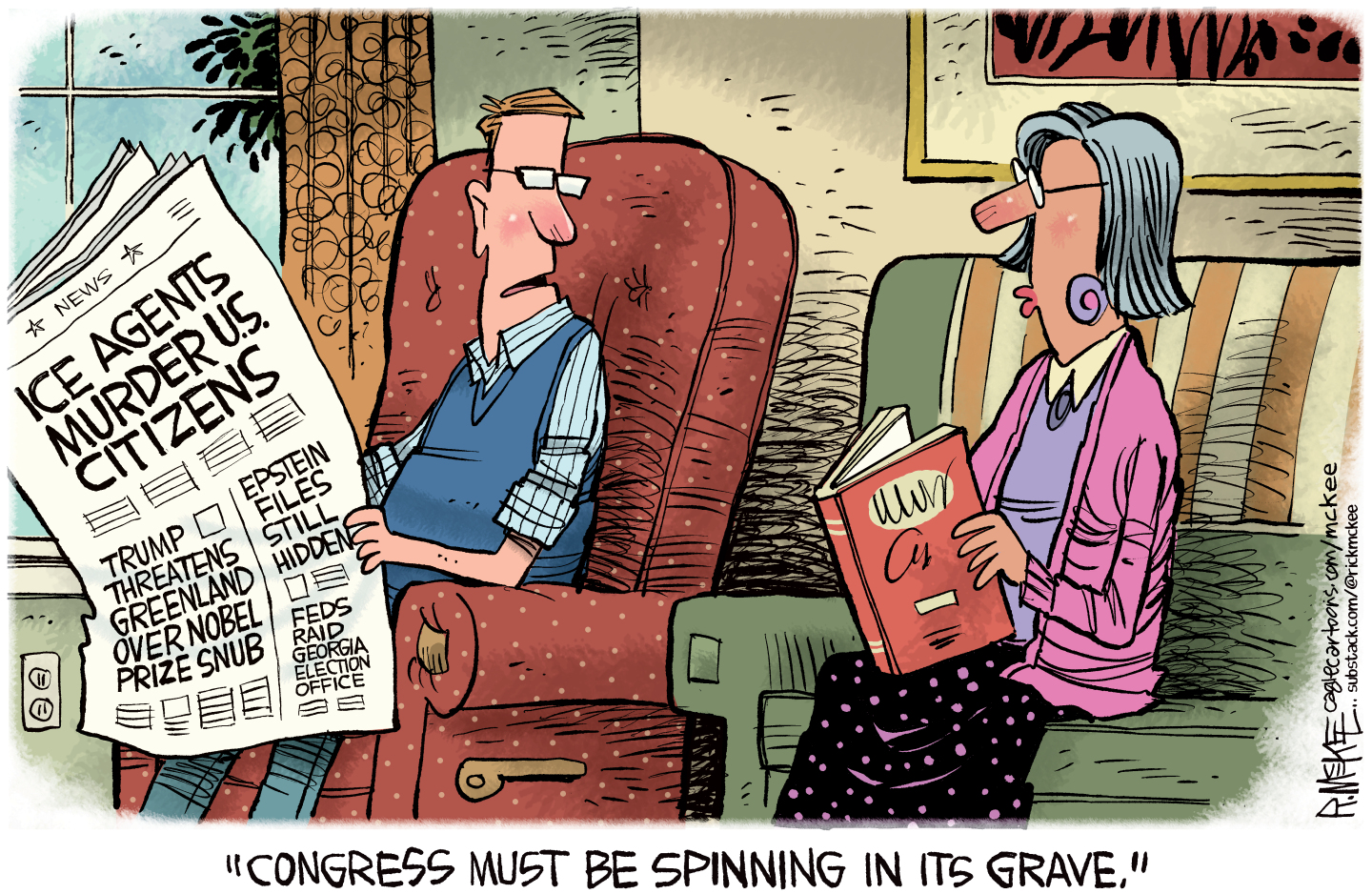

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred