Dump Trump? These 8 wild conventions show that anything is possible

Many Americans are expecting ferocity and fireworks in Cleveland. They'd have to be pretty fiery to top these crazy conventions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Anti-Masonic Party kicked off the American practice of picking a presidential nominee at a convention in December 1831. Since then, political conventions have slowly transformed from contests where party bosses, elders, and power brokers schemed and maneuvered in smoke-filled rooms to anoint their man the party's standard bearer to today's largely scripted unity parties.

But this year, you can throw out the script.

As Republicans gather in Cleveland the week of July 18 to (probably) nominate Donald Trump, and Democrats convene in Philadelphia the week after that to nominate Hillary Clinton, there are more question marks than we typically see during presidential convention season. At the very least, Trump promises to put on a good show full of unscripted moments. But his Republican opponents are still talking about fomenting a coup. Though the most likely scenario is a reluctant Trump coronation, really, anything could happen.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Don't believe us? Just look to history to remind yourself that during a political convention, anything is possible.

1. 1924 Democratic Convention (New York)

The Democrats entered the 1924 convention deeply divided between Al Smith, New York's Irish Catholic governor backed by urban and anti-Prohibition delegates, and former Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, a son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson who was championed by anti-alcohol delegates, Protestants, and the Ku Klux Klan.

With hooded Klansmen burning a cross and vandalizing an image of Smith outside the convention hall, Smith supporters came up one vote shy of approving a platform plank condemning the Klan as violent and un-American, and the subsequent shouting match got so intense that police had to be called in to break up the melee. (Smith backers, Politico says, were yelling "Ku Klux McAdoo!" while McAdoo partisans countered with "Booze! Booze! Booze!")

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After 16 days and 102 votes, Smith and McAdoo realized neither was going to win so they both withdrew, leaving John W. Davis, a federal judge and former solicitor general, to win as the compromise candidate — and lose badly to incumbent President Calvin Coolidge.

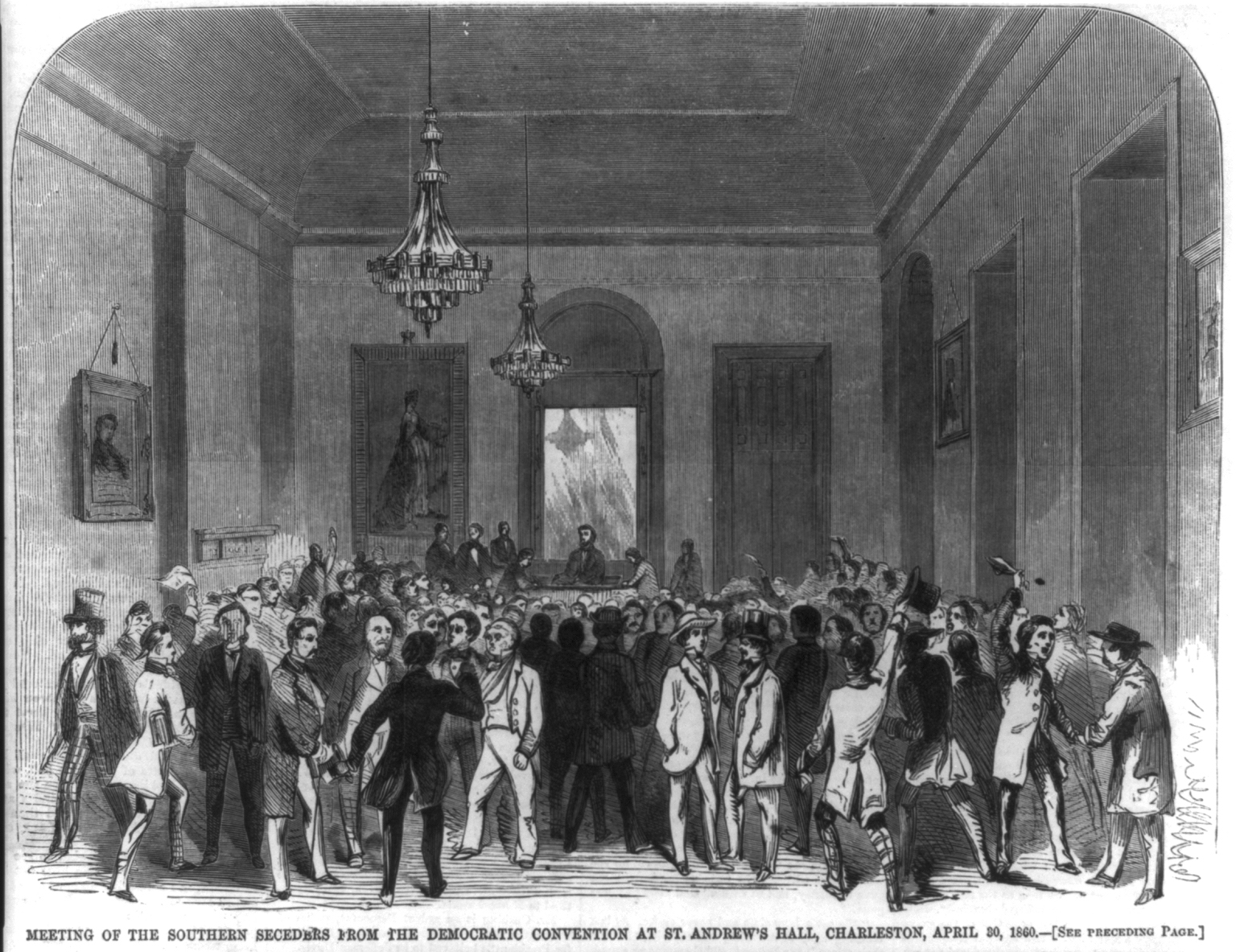

2. 1860 Democratic Convention (Charleston, South Carolina)

The Democratic Convention in Charleston is the only one in U.S. history to end without a nominee. With the party split deeply over slavery — the Northerners, backing Sen. Stephen Douglas (Ill.), were generally in favor of leaving the slavery decision up to states while the Southern Democrats wanted the party to champion a federal slavery code. When the Northern faction amassed enough delegates to kill the pro-slavery platform plank, chaos broke out on the floor. "The house was in an uproar," a reporter recounted at the time, with "a hundred delegates upon the floor and up on chairs, screaming like panthers and gesticulating like monkeys."

After 57 ballots, Douglas couldn't get the requisite number of votes to win the nomination, and after the delegates from seven Southern states walked out, there weren't enough delegates to nominate anybody, so the Democrats closed up shop and gathered again six weeks later in Baltimore. There, the Northern Democrats nominated Douglas, but the Southern faction held its own convention and nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge, a staunch defender of slavery. This was the only time a major political party ran two opposing candidates, and with a conservative third party (Constitutional Union) also running a candidate, Republican Abraham Lincoln easily won the presidency.

Before Lincoln was sworn in, a sizable chunk of the South seceded from the United States, teeing up the Civil War.

3. 1968 Democratic Convention (Chicago)

In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson announced he wasn't running for re-election because of the Vietnam War, the leading candidate to replace him (Robert F. Kennedy) was assassinated in June, and surviving anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy was passed over at the Democratic convention in Chicago for Johnson's vice president, Hubert Humphrey, who did not compete in the primary. There was some drama inside the heavily fortified convention hall, but Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley had refused to issue permits for an estimated 10,000 antiwar protesters outside, and when their protests ran into the 23,000 police and National Guardsmen Daley had deployed to keep order, things got very ugly on national TV.

At one point, protesters clashed with police outside a Hilton, and network TV news broadcast 17 minutes of it live, with the protesters taunting the cops with chants of "The whole world is watching." So were Democrats inside the convention hall, and when Sen. Abraham Ribicoff (Conn.) denounced the "Gestapo tactics on the streets of Chicago," Daley was filmed standing up, pointing a finger at Ribocoff, and yelling inaudible obscenities, including calling the senator a "Jew son-of-a-bitch!"

Humphrey narrowly lost to Richard Nixon in the general election.

4. 1972 Democratic Convention (Miami)

The chaos of the 1968 Democratic Convention led to democratic reforms proposed by Sen. George McGovern (S.D.), opening up the modern system of nominees being selected through primaries and caucuses. McGovern, representing the left wing of the party, used the new system to beat out a crowded field that included Humphrey, early frontrunner Sen. Ed Muskie (Maine), and Gov. George Wallace (Ala.). The old guard, stripped of much of their power, coalesced into an "ABM" (Anybody But McGovern) faction, but when they tried to change the rules for how California delegates were apportioned, the McGovern loyalists pushed back and stripped the credentials of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley's slate of Illinois delegates and replaced them with an unelected slate made up largely of women and minorities.

The democratic spirit was so strong that a parade of vice presidential candidates refused to bow out even after it became clear that Missouri Sen. Thomas Eagleton (who later dropped off the ticket due to leaked mental health issues) would win the nod. Their speeches pushed McGovern's acceptance speech back to 3 a.m., meaning almost nobody outside the Miami convention hall watched it. Eight years later, the Democratic Party introduced superdelegates to restore some order to the process.

5. 1900 Republican Convention (Philadelphia)

The drama at the turn-of-the-century Republican convention wasn't the top of the ticket — President William McKinley was running for re-election unopposed. But his vice president, Garret Hobart, had died in November 1899, and McKinley's top adviser, Sen. Mark Hanna (Ohio), was opposed to the man put forward as McKinley's running mate: New York Gov. Theodore Roosevelt. "Don't any of you realize," Hanna warned, "that there is only one life between that madman and the presidency?"

McKinley did not back Hanna's efforts to put forward an alternate candidate, and a reluctant Roosevelt was being championed by New York political bosses who wanted the young reformer out of the governor's mansion. McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, and Roosevelt became the youngest person ever to ascend to the presidency.

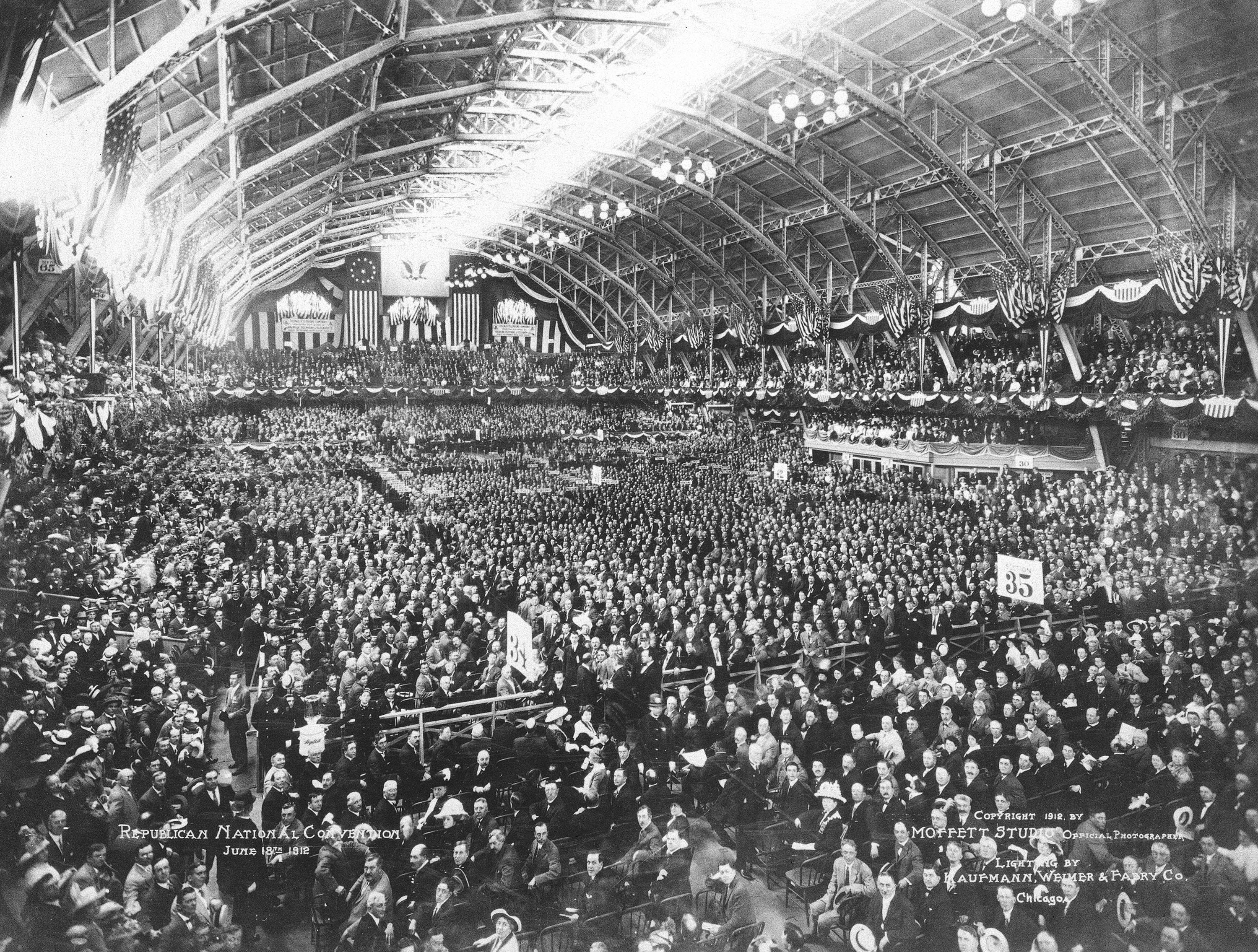

6. 1912 Republican Convention (Chicago)

Theodore Roosevelt did not run for a second full term in 1908, backing his protégé William Taft, who won the election. But by 1912, Roosevelt was disenchanted with Taft's business-friendly conservatism, so he challenged him. "On February 24, [Roosevelt] announced that he would accept the nomination, and the greatest pre-convention struggle in American history was on," writes the historian Eugene H. Roseboom in his History of Presidential Elections. Roosevelt won primaries in Ohio, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, but in Chicago, Taft used his control of the Republican National Committee to stack the convention with loyalists.

"Squads of police were present to uphold the rulings of the chair," wrote Roseboom. "Few present knew of the concealed barbed wire under the decorations around the railings to the rostrum." Roosevelt gave a thundering speech, branding the president a thief and famously declaring, "We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord!" And when the Taft delegates nominated Taft for re-election, Roosevelt formed his own Progressive (Bull Moose) Party. During the campaign, somebody shot Roosevelt during a speech in Wisconsin, and Roosevelt finished the speech with the bullet still lodged in him.

That stamina and drive boosted Roosevelt to second place, after Democrat Woodrow Wilson, and Taft became the last major party candidate not to place first or second. (Socialist Eugene Debs came in fourth at 6 percent, in the best showing for the Socialist Party to date.)

7. 1964 Republican Convention (San Francisco)

The GOP's 1964 convention was a battle between the supporters of arch-conservative Sen. Barry Goldwater (Arizona) and moderates represented by New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, whose own campaign was sunk earlier in the year due to his divorce and remarriage. "The hour is late," Rockefeller said, "but if all leaders in the moderate mainstream of the Republican Party will unite upon a platform and upon Governor [William] Scranton," who had just entered the race, "the moderate cause can be won." It couldn't.

Goldwater was a hawk who advocated military intervention in Eastern Europe and a staunch opponent of the Civil Rights Act. When the GOP delegates defeated a proposal to moderate the Goldwater stance on civil rights, by an 897-409 vote, Northeastern moderates were furious, and during a floor fight over immigration, a Goldwater backer almost caused a fistfight when he mocked Italian-Americans. "The venom of the booing and the hatred in people's eyes was really quite stunning," one moderate recalled. A leader of the New York Young Republicans said, "I felt like I was in Nazi Germany."

Rockefeller's anti-extremist speech was drowned out by loud jeering, while Goldwater declared that "extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice." He went on to lose to LBJ in a landslide.

8. 1976 Republican Convention (Kansas City)

The 1976 convention battle between President Gerald Ford (the only president never elected president or vice president) and former California Gov. Ronald Reagan is probably the last convention where it wasn't clear going in who would be the nominee when the balloons dropped. Ford arrived at the convention with more delegates and popular votes than Reagan, but not enough to clinch the nomination. Between Reagan's committed faction of delegates and Ford's presidential sweeteners, the nomination could have gone either way.

Reagan gambled that he would peel away Ford delegates by taking the unusual step of announcing a running mate, moderate Sen. Richard Schweiker (Pa.), and trying to force Ford to announce his. The Schweiker gambit backfired, alienating Reagan's conservative backers and winning him few if any Ford supporters. When Reagan's faction lost a rules vote trying to force Ford to name a running mate, Reagan's bid was done. Ford went on to lose to Jimmy Carter, whom Reagan defeated four years later.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred