What is Donald Trump's religion?

Trump worships power and strength more than anything. That's downright Nietzschean.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is Donald Trump's religion?

Ever since he explained (several times) that he's never asked God for forgiveness about anything, we know it can't be Christianity, despite his on-the-record assurances to the contrary. If there's one requirement for entering the club of Christianity, it's asking forgiveness for your sins.

So, what is it? Where do Trump's worldview, moral instincts, and spiritual beliefs truly lie?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Matthew Schmitz, literary editor of the intellectual magazine First Things, and one of the sharpest young Catholic writers today, locates Trump's Gospel in the works of Norman Vincent Peale, America's mid-century promoter of "positive thinking."

Surely you've heard of Peale's idea. It has, after all, become more famous than Peale himself. The theory of positive thinking states that all you need to feel better and happier in life is to highlight the positive things around you. Forget about the bad stuff. Don't beat yourself up or judge yourself. Oprah Winfrey has turned Peale-ism into a bigger business than Peale ever could have. The power of positive thinking is peddled by other pop-spiritual gurus from Joel Osteen to Eat Pray Love's Elizabeth Gilbert, who goes on a journey of self-discovery whose main discovery is that she shouldn't judge herself for abandoning her family to go on a journey of self-discovery.

Schmitz correctly identifies where this gospel of positive thinking can contradict the actual Christian gospel:

Where the Bible urges man to search his heart and know his faults, Peale encourages him to "make a true estimate of your own ability, then raise it ten percent." For Jeremiah the heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked, but for Peale its dark recesses are bathed in California sunshine.Thus the necessity of repentance recedes. It is important to think positively, and a negative thought, such as Domine, non sum dignus, can be injurious to spiritual health. Yet the gloomy aspect of traditional Christian practice is also the wellspring of Christian compassion. At the moment a Christian asks for forgiveness, he must acknowledge his own weakness and look mercifully on the weakness of others. In the Our Father, the Christian asks that he be forgiven, just as he in turn forgives. From the holy terror that Peale called "fear thoughts" comes the light of Christian love. [First Things]

And here's the Trump connection, Schmitz avers: Trump "has taken Peale's teaching to its logical conclusion." In Trump's case, positive thinking has convinced him that he's so awesome, he no longer (or maybe he never did) recognizes himself as a sinner, which means he doesn't have sympathy for the "losers" around him and feels free to look down on them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's a kernel of truth in this, but I'm afraid it is buried in a lot of error.

Schmitz's tirade against the gospel of positive thinking is a trope of conservative Christian discourse. Indeed, that heresy has a big pedigree in contemporary culture. But like most conservative Christian jeremiads against heresies, they fail to recognize that heresy is almost always a response to a failure of orthodoxy. (As a Catholic, I believe Martin Luther's theology is wrong, but he was certainly right to be outraged at the Church's corruption.)

If there is a heresy of positive thinking, then there is surely an equal and opposite heresy. Call it the Gospel of guilt, which anyone familiar with the Christian conservative milieu surely has encountered, and which surely has wrecked many lives.

The heralds of positive thinking are responding to a very real and very serious problem for all of us, which is self-loathing and self-sabotaging. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, the medieval monk who is recognized as a beacon of orthodoxy, once opined that it's impossible to love others — the Christian's first duty — without first loving oneself. C.S. Lewis in his own way agreed, famously pointing out that humility, a Christian virtue, is not "thinking less of oneself, but thinking of oneself less." If the current pope said this, I don't doubt he would be swiftly rebuked as peddling a postmodern Gospel of positive thinking.

Schmitz talks about the spiritual importance of the fear of hell. "Peale meant to preach a gentle creed, one that made hellfire and terror into mere afterthoughts," Schmitz writes, dripping with evident disdain. In an essay criticizing the pope's recent letter on the family, which was praised by countless Christian conservatives but left a sour taste in my mouth, Schmitz insists that we must live in "fear of God."

Meanwhile, Christian tradition has held that moral behavior accomplished through fear of hell is, in the words of Jesus when he appeared to Catherine of Siena, "slavish love," which is immature and must grow into more mature forms of love.

Don't get me wrong: The fear of hell has saved many people from making terrible decisions. But Christian conservatives like Schmitz fail to recognize how many childhoods and lives have been ruined by the Gospels of guilt and fear, and how the heresies they seem to see as alien phenomena dropped from the sky are really the products of the excesses of their intellectual and spiritual forebears.

But Christian conservatives are so obsessed with their pet peeves that they go so far as confusing Trump for Oprah. Trump's intellectual and spiritual ancestor is in no way the drab Norman Vincent Peale, but instead, the flamboyant Friedrich Nietzsche.

I'm certainly not original in thinking this. Here's my colleague from The Week, Damon Linker, making the case, and here's my Ethics and Public Policy Center colleague Peter Wehner. But it's worth repeating that Trump comes not from heterodox Christianity, but from anti-Christian paganism.

Trump worships power and strength more than anything, and he does so in a way that bears no resemblance to Peale but is totally consonant with Nietzsche's vision. While Nietzsche would find Trump terribly tacky (although the middle-class pastor's son was never as aristocratic as he thought of himself), Trump certainly has an aesthetic that Nietzsche commends to the Übermensch, a concern foreign to Yankee liberal protestant preachers. The Übermensch will make his life into a work of art, a self-creation, Nietzsche writes, a motto that Trump took to heart, he the empty core surrounded by a façade of reality TV and branding deals.

People have turned to heretical, postmodern, "feel good" forms of religion because they fulfill a genuine need that traditional forms of religion left unmet. And by railing without understanding, conservative Christians only perpetuate the cycle that drove so many people away from the faith. Mistaking Trump's beliefs for something they plainly are not because of this obsession shows that something has gone awry.

When I was a child, my mother once quizzed me: What was Judas' worst sin? Betraying Jesus, of course, I answered. No, my mother answered, his worst sin was what he did after that, which was to kill himself in guilt. He did so because he believed God could never forgive him. And that is the worst thing of all, isn't it? God can forgive anything, except if you don't ask him. Judas probably loathed himself too much to ask for forgiveness. I think that's what Jesus meant when he said it would be worse for him to have a millstone tied around his neck.

Like a good Christian, I fear hell. And I know that if I end up there, and if anyone is there with me, it will be because of excessive self-loathing, not excessive self-love. Perhaps that would be the case even, deep down, for Trump.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

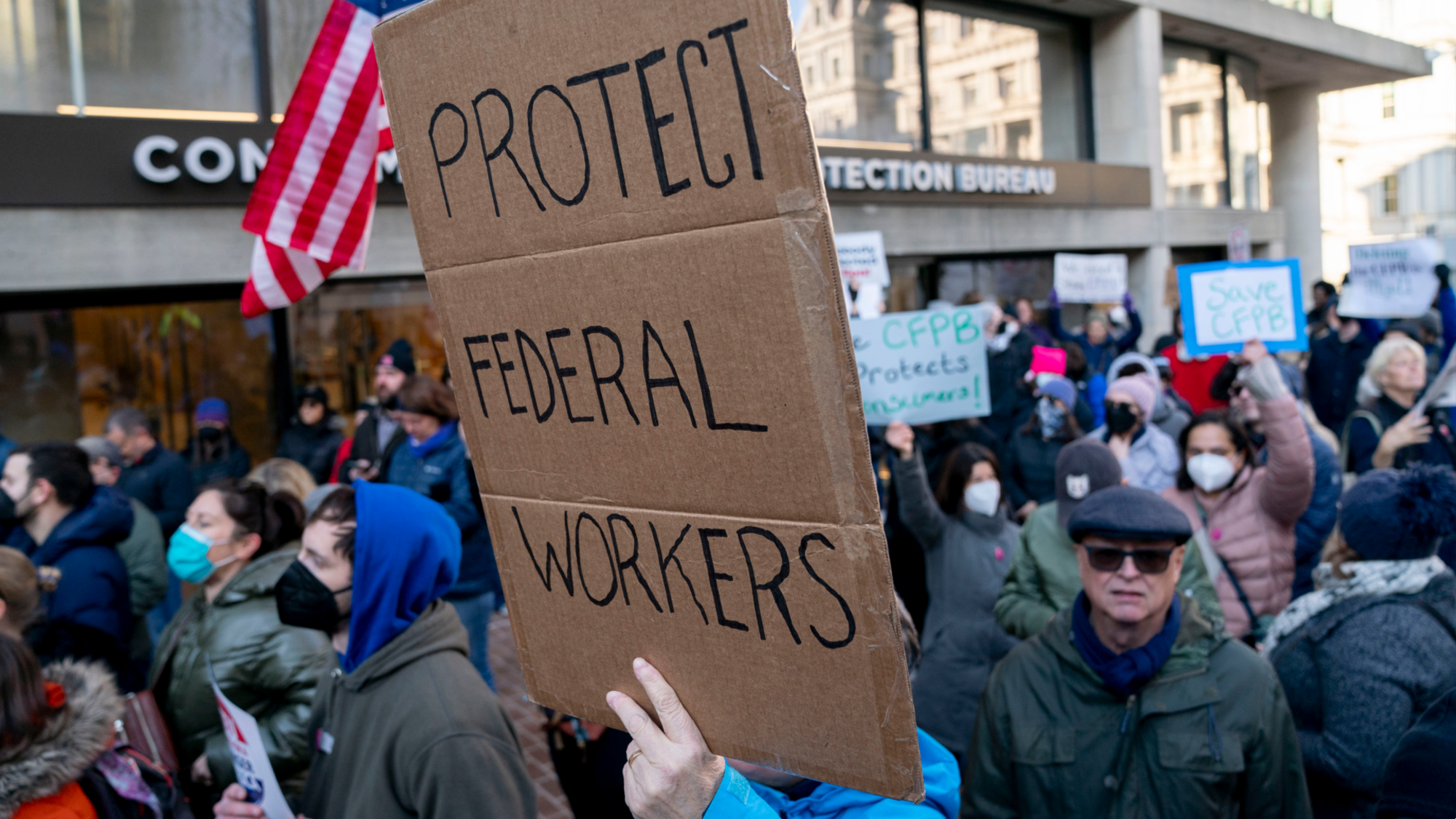

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers