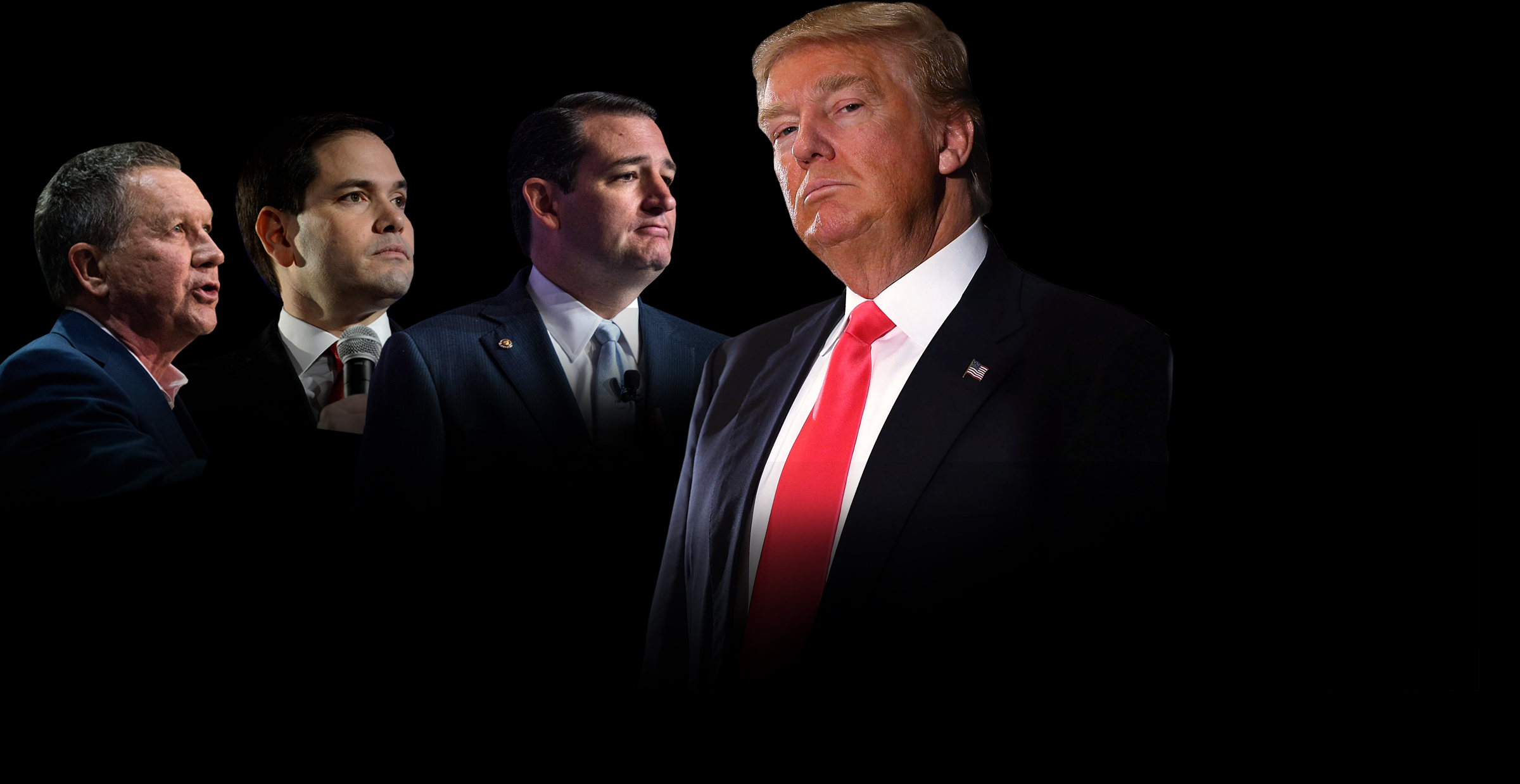

Why conservatives failed to stop Donald Trump

It's not that Trump is a good candidate. It's that conservatives can't stop their bickering for long enough to rally around someone better.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the Republican National Convention in full swing this week, it's all but certain Donald Trump will soon go from "presumptive" Republican nominee to just the Republican nominee. As a card-carrying founding charter member of #NeverTrump, the hashtag-based movement to prevent Trump from winning the nomination, this fills me with despair. Clearly, we've failed. (I know, I know. Who thought we could be stopped when we had a hashtag on our side?)

But there are many reasons why #NeverTrump never worked. The sheer number of candidates vying for the Republican nomination allowed Trump to win primaries despite having only 30 percent of the vote early on. All the candidates were waiting for someone else to attack Trump instead of doing it themselves (except for Jeb Bush, who did it in his hapless Jeb way), much to the detriment of the entire group. It was a sort of political version of the prisoner's dilemma. And by the time they finally started working together to bring him down, it was too late.

But there was a deeper problem: #NeverTrump never coalesced around an alternative candidate because the conservative movement is in a full-blown identity crisis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Despite there being many other alternatives who, while flawed, would have surely been better than Trump, conservatives couldn't get over their petty differences and rally convincingly around a single one. They all seemed to have some sort of deal-breaking problem.

Ted Cruz is a perfect rock-ribbed conservative on paper, who seems to have been built for politics in a factory somewhere. But he's got an attitude problem that makes him loathed by large segments of the Republican Party, including conservatives who otherwise agree with him on virtually everything, as my colleague Michael Brendan Dougherty aptly explains.

Marco Rubio has lifetime rating of 98 percent from the American Conservative Union. He's also, well, you've heard it all before, right? He's smart, young, telegenic, and Latino. He has a great life story. He's a sitting senator in America's most critical swing state. And so forth. But his support for comprehensive immigration reform makes him anathema to a segment of the party.

Moderate John Kasich seemed to enjoy insulting conservatives. The less said about him, the better.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At some point, there was even talk that the white knight of the Republican Party might have been Mitt Romney, who certainly seems as close to a "consensus" GOP candidate as it gets. Aside from the fact that Romney took himself out of the running, there's a deeper problem, which is that, in a year of party base revolt, nominating a man who seems to embody the establishment is probably a bad idea.

Every one of the viable candidates represented a faction of the Republican Party: evangelicals for Ted Cruz, upper-middle-class conservatives for Marco Rubio, establishment for Mitt Romney. And these factions increasingly can't stand one another. It's like a failing marriage, where the other spouse's minor flaws, which used to be a livable quirk or even cute when the union was buttressed by love, becomes a further reason to break up.

The well-known tensions at the heart of the conservative movement, between social and economic conservatives, between foreign policy hawks and realists, and so on, made it easy for someone like Trump, who had absolutely no interest in the rival factions' internecine warfare and instead could appeal straight to the gut of a relative majority of the party's working-class base, to, like a toddler, grab the strange object, shake it like a rattle, and then shatter it by throwing it to the floor.

This isn't the first time the GOP, like any political party, has encountered a setback, of course. But it is certainly the first time that it, or really any other party in recent memory, has ended up nominating a presidential candidate who happens to be so obviously unsuited to the office which he seeks, so obviously doomed in a general election campaign, and so at odds with what the party itself claims to stands for. Even Barry Goldwater, who lost in a landslide in 1964, only ticked one of those three boxes. Walter Mondale lost in a landslide, but as a former vice president, he was a consummate insider, not the total outsider that Trump is.

What is conservatism all about? White identity politics? Boosting corporate profits? I would argue it's about a certain view of human flourishing informed by millennia of learning by trial and error. These lessons have produced some of the most profound political, and even spiritual, traditions in history. Other people will have different views.

Rebuilding the conservative movement after Trump will not just require a good candidate and good policies. It will also require asking, and then answering in a resounding voice, an important question: What does it mean to be a conservative?

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 February

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

Nordic combined: the Winter Olympics sport that bars women

Nordic combined: the Winter Olympics sport that bars womenIn The Spotlight Female athletes excluded from participation in demanding double-discipline events at Milano-Cortina

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japanese heritage

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japanese heritageThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred