Democracy vs. the mob

On the dark side of democracy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What's the difference between democracy and rule by mob?

This is a pressing question. A man who has aptly been described as "the most successful demagogue-charlatan in the history of U.S. politics" managed to accumulate enough votes to become the Republican nominee for president. Then he enjoyed a substantial bounce in the polls following a chaotic convention filled with blatant fear-mongering and an acceptance speech that set himself up as the strong-man savior of the nation.

Meanwhile, a man who became a Democrat only when he declared his candidacy for president (and has now resolved to leave the party again when he returns to the Senate) came within striking distance of winning a presidential nomination. And like petulant children, his supporters continually disrupted the Democratic convention.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Is this democracy or rule by mob?

As the British historian of political thought John Dunn has shown in a useful primer on the subject, the idea of democracy has a history — and that history can help us to gain much-needed perspective on some of the most troubling tendencies of the present political moment. While what the word "democracy" denotes has changed very little over the centuries and millennia — a form of government in which the people or "the many" rule — the way philosophers and intellectuals have evaluated it has shifted radically. What was once considered one of the worst forms of government is presumed by most today to be the only legitimate form of government.

But have we taken our reverence for the concept of democracy too far? Have we forgotten the perennial defects and dangers that political thinkers prior to the last two centuries consistently detected in democracy?

For Greeks writing in the ancient Athenian city state, democracy was simply mob rule. It was the politics of the crowd. It was devoid of reason. It was fickle, impetuous, ignorant, irresponsible, and easily manipulable by the rhetoric of sophists and demagogues who used rank flattery of base passions and fears to move public opinion whichever way they wished. This is why (as Andrew Sullivan recently explained in an important essay for New York magazine) Plato held that a pure democracy is always one step away from devolving into tyranny, the worst form of government of all: Because a sufficiently accomplished manipulator of the crowd can ride to power on waves of popular adulation and then turn himself into a tyrant.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Aristotle shared Plato's dark view of democratic government, but he nonetheless proposed that a modified form of democracy that mixed elements of oligarchical rule of the wealthy few could produce a relatively decent form of politics. In such a mixed regime, the worst aspects of each defective form of government would restrain the worst aspects of the other.

Over the next 2,000 years, Aristotle's idea of moderating the excesses of democracy in a mixed regime resurfaced from time to time — in the writings of select political philosophers in ancient Rome and the European Middle Ages; in the goals of the conciliar movement within the medieval Catholic Church. But it wasn't until the 17th and 18th centuries that a wide range of authors actively revived Aristotle's suggestions.

Spinoza, Locke, Montesquieu, the American constitutional framers, and several other participants in the transnational reform movement known as the Enlightenment aimed to adapt classical insights to the changed circumstances of modernity. They argued that institutions could be devised to mix elements of democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy, preserving the best and neutralizing the worst aspects of each pure form. This new version of a mixed regime (combining democratic election with representative institutions and various anti-democratic checks) would be uniquely well-suited to govern modern, commercially based political communities of national scope.

Or so these authors claimed.

Starting around the time of the French Revolution, the reservations about democracy that had led the leading figures of the Enlightenment to insist on checking the excesses of democracy began to give way to expressions of outright enthusiasm for the direct democratic rule of the people. Now democracy was not just an acceptable form of government with distinctive strengths and weaknesses but simply the best form of government — the form toward which all peoples ultimately aspired and that all political leaders (whether democratically elected or not) claimed to respect and champion.

In the U.S., the rapidly rising reputation of democracy translated into a series of reforms that dismantled numerous constitutional and customary restraints on direct democratic rule. And then those reforms were followed up by more recent moves to make Congress more transparent to the people and responsive to public opinion (which was now constantly monitored and publicized through polling).

Today democracy is considered the only legitimate form of government — and increasing the democratic character of any existing government an unalloyed good. But is it?

One reason why early modern political philosophers looked somewhat more kindly on democracy than their ancient counterparts is that they presumed that in the much larger political communities of modernity the demagogic manipulation of the crowd would be considerably more difficult to achieve than it had been in the comparatively tiny city states of antiquity. But by the early 20th century, technology (electronic speakers to amplify voices at massive public rallies, radio, film, television) had enabled the old defects of democracy to resurface on a vastly larger scale. In our own time, 24/7 partisan news and social media (especially Twitter) take the capacity for mass public manipulation to levels unthinkable in past ages.

Now we know that a virtual mob can even be mobilized to deliver control of a major political party into the hands of a man any political philosopher in Western history would instantly recognize as a demagogue and potential tyrant.

That raises the question of whether we may have gone too far in our one-sided adoration of democracy — and whether there are any democratically acceptable means of dispersing a mob of millions once it has formed. The difficulty of finding any principle by which to temper a democracy's excesses is one reason why Plato looked upon the form of government so skeptically and warned so ominously about its tendency to degrade into something much worse.

Was Plato too pessimistic?

We may receive a tentative answer a little more than three months from now.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

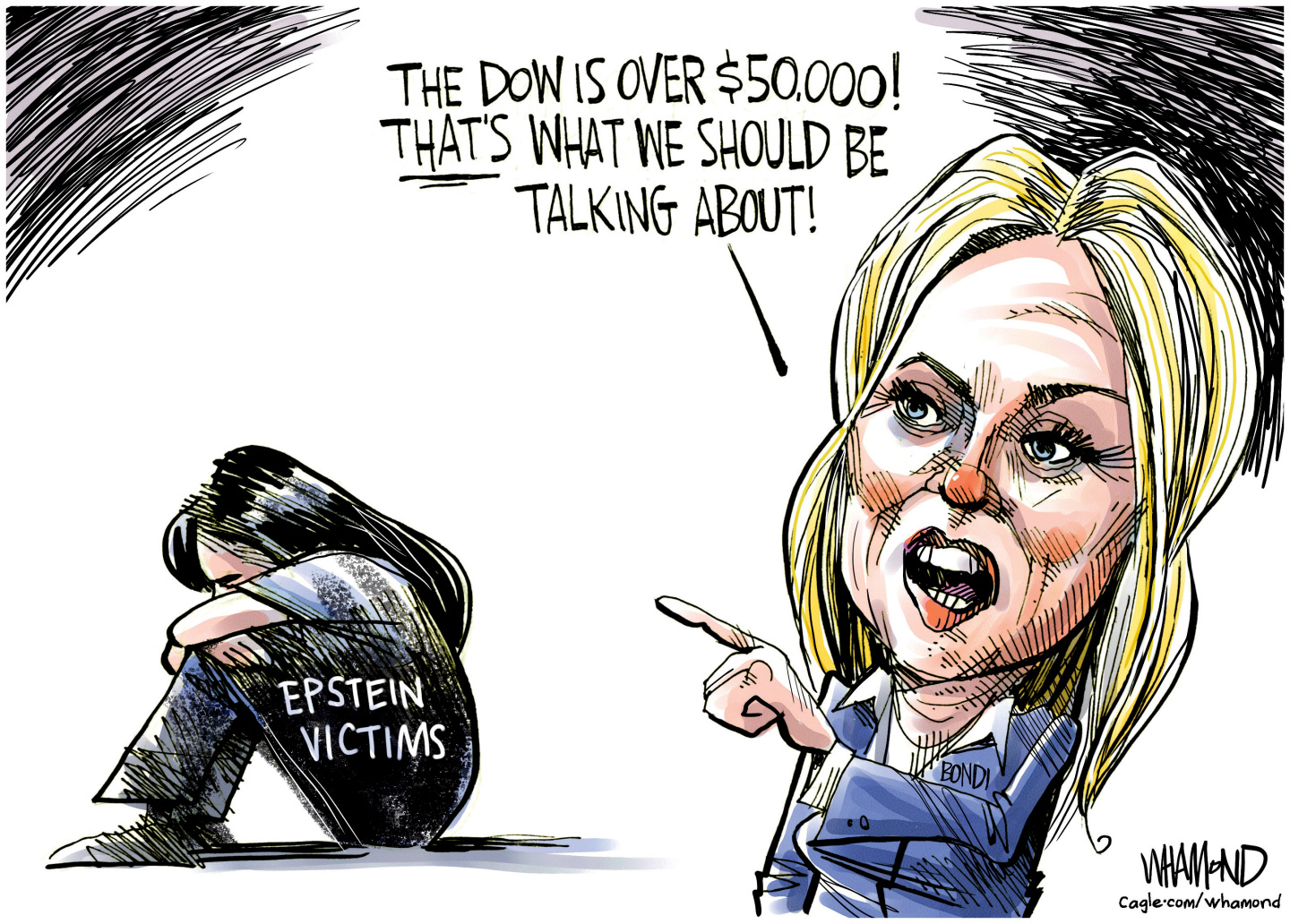

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred