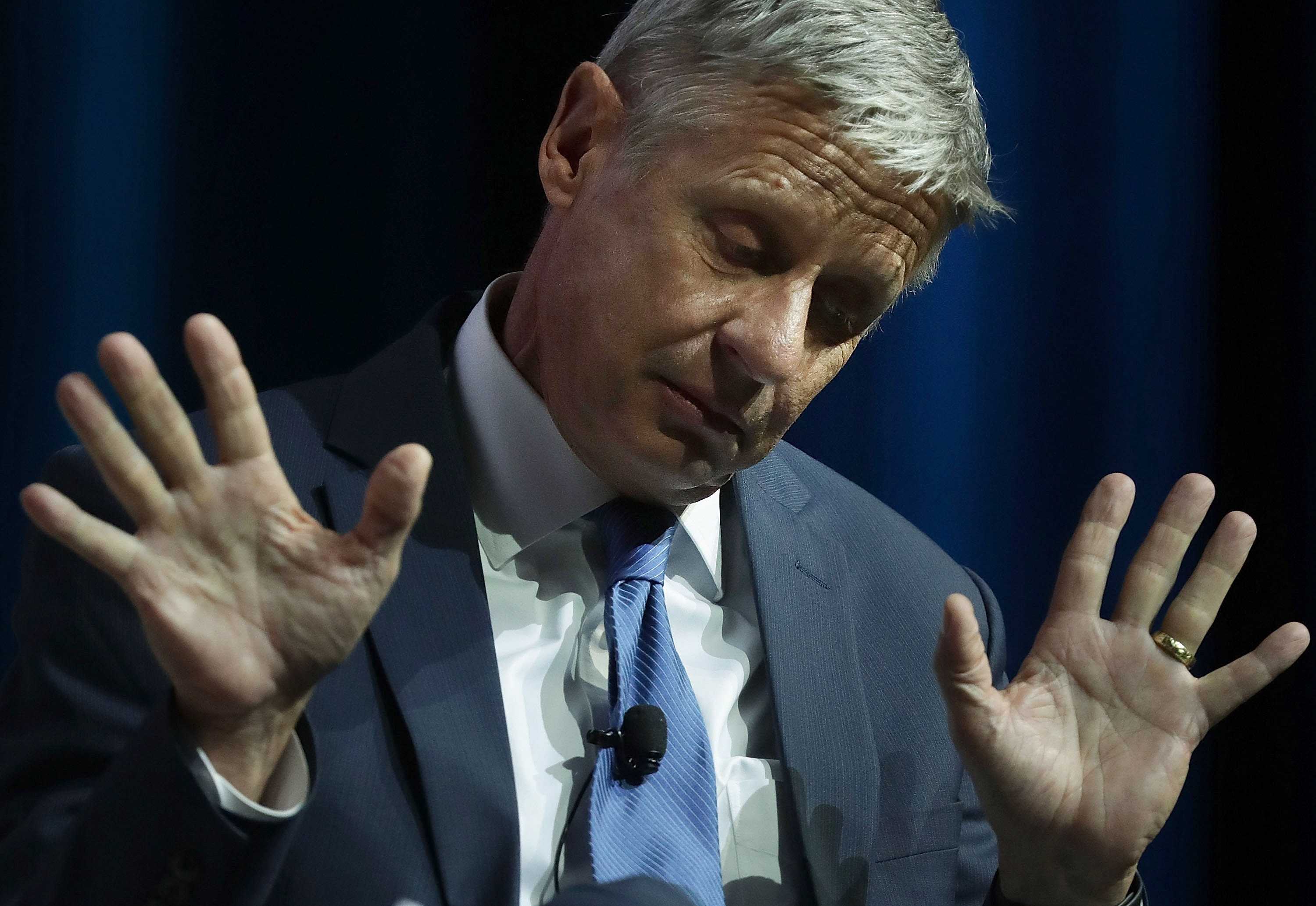

Here's what Gary Johnson should have said about Aleppo

"So, now that I know what and where Aleppo is, what would I do about it as president? I don't know. Do you?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Hello, I'm Gary Johnson, the Libertarian Party candidate for president, and I don't know what to do about Aleppo.

Actually, when MSNBC's Mike Barnicle first asked me about it, I didn't even know that Aleppo was a place — I thought it was an acronym. Which is pretty embarrassing — at least The New York Times knew Aleppo was a city, even if they weren't sure which one. But, as I learned in about five minutes from Wikipedia after I left the studio, Aleppo is in fact the site of a crucial conflict between the Syrian government and a variety of rebel groups. The four-year struggle has destroyed much of this ancient city, and resulted in more than 25,000 fatalities in the city and the surrounding province through the beginning of this year.

So, now that I know what and where Aleppo is, what would I do about it as president?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I don't know. Do you?

Hillary Clinton certainly doesn't. She was a strong advocate of intervening in the Syrian civil war from its earliest days, just as she was one of the strongest supporters of George W. Bush's war in Iraq and of President Obama's war in Libya, which she called "smart power at its best." Those countries are now, along with Syria, hotbeds of ISIS activity. She has repeatedly called for a no-fly zone in Syria, at the risk of war with Russia, even though a no-fly zone would be ineffective at protecting civilians.

Donald Trump certainly doesn't. His plan is to let Russia defeat ISIS. But Russia never had any interest in defeating ISIS, but instead focused on shoring up Bashar al-Assad in his battle against other rebel groups — the groups active in cities like Aleppo. In other words, Trump's plan to save Aleppo is to let Russia help Assad destroy Aleppo.

So I really don't know what to do about Aleppo. And in that ignorance, I've got good company.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the real question is: Should I know what to do about Aleppo? Should you?

The primary responsibility of the commander-in-chief is to protect the United States from foreign threats. Syria has not attacked the United States, and has no plans to do so. Its allies, Russia and Iran, are not imminent threats to the United States, and inasmuch as they may pose threats in the future, the survival of the Syrian regime will not materially improve their ability to threaten America's vital interests. ISIS is an exceptionally horrific excrescence, but the attacks on Western targets attributed to it are the largely work of at most loosely affiliated individuals inspired by the group. And ISIS isn't even active in Aleppo.

Syria is not a serious national security threat to the United States. Syria is a humanitarian catastrophe. Hundreds of thousands of people have died in the civil war. Millions have been displaced from their homes or fled the country entirely. That suffering makes a claim on our compassion, even if we don't know how to end its source, and we should not ignore that claim.

We should do whatever we can to help refugees escape the carnage, and, in conjunction with our allies and neighboring countries, provide funds and resources to house, feed, and care for them. We should strongly support diplomatic efforts to end the conflict as swiftly as possible, and use our leverage with both allies and rivals to subordinate their other geopolitical interests to that humanitarian aim — and be similarly willing to subordinate our own such aims. We should facilitate the repatriation of refugees once the conflict is ended — or settle them permanently among ourselves in those cases where repatriation is not a realistic option. But we should be far more eager to take refugees in than we are to intervene more deeply in a conflict that none of us should have confidence we understand how to solve. And so long as we don't know how to solve the conflict, we should do less — certainly less killing — rather than more.

Some will call that a lack of moral clarity. But I am mystified how it is more clearly moral to kill Syrians, and risk the deaths of America's fighting men and women, with neither a reasonable prospect of success nor any legal justification for such action.

Others will call it a lack of leadership. But I can't understand how leading the American people into another failed war could be preferable to staying out. Nor can I understand why we should be eager to encourage other groups, even those with very legitimate grievances, to initiate hostilities in the hopes of drawing in American "leadership" to bail them out.

My opponents and the media seem to believe that if you are running for president, you have to have an answer for every question — indeed, that you are disqualified from the office if you don't have a solution to every problem. One of my opponents thinks that if you study hard enough, you will inevitably find the answer. My other opponent thinks that blindly bluffing your way through any question is a good enough answer. But if you ask them what to do about Aleppo, they'll both say they know, and that anybody running for president certainly ought to know.

I'm the only major candidate honest enough and secure enough to admit what's true of all of us: I don't know what to do about Aleppo.

Do you?

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.