The end of the inflation consensus

The conventional wisdom about the economy is falling apart. What will take its place?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Is there a rebellion brewing in the Federal Reserve?

On Wednesday, America's central bank released the minutes from its September meeting, which yet again ended with a decision to hold the central bank's interest rate target steady at 0.25 to 0.5 percent. But the minutes reveal ever more dissension in the ranks: Three voting members wanted to hike rates again, and even those who voted for the hold said it was a "close call" and they think a hike would be appropriate "relatively soon."

The problem for Team Rate Hike is they don't have the data on their side. They just have a story. It's a plausible story, but most importantly it's a story economic policymakers and commentators in high places have been telling one another for years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That story says as the unemployment rate falls, inflation will rise, because as the economy runs out of new people to employ, the only way employers can lure away workers from the competition is by bidding up wages — which boosts prices in turn. It also says that once inflation starts rising, it's very difficult to stop without jacking interest rates up so high that the Fed sparks a recession. Since the unemployment rate has been at or below 5 percent for all of 2016, plenty of Fed officials are getting skittish.

Yet inflation has stubbornly refused to behave in the predicted fashion. It has run well below the Fed's 2 percent target for almost the entirety of the recovery, is far from that target now, and you have to squint very hard to see any indication in the data that it's about to take off. The idea that if it does start rising it will be unstoppable is based on one freak historical confluence of forces that's very unlikely to ever repeat itself. Growth in nominal wages — one of the best signals of how much employers are competing for workers — is still well below where it was at the peak of previous business cycles.

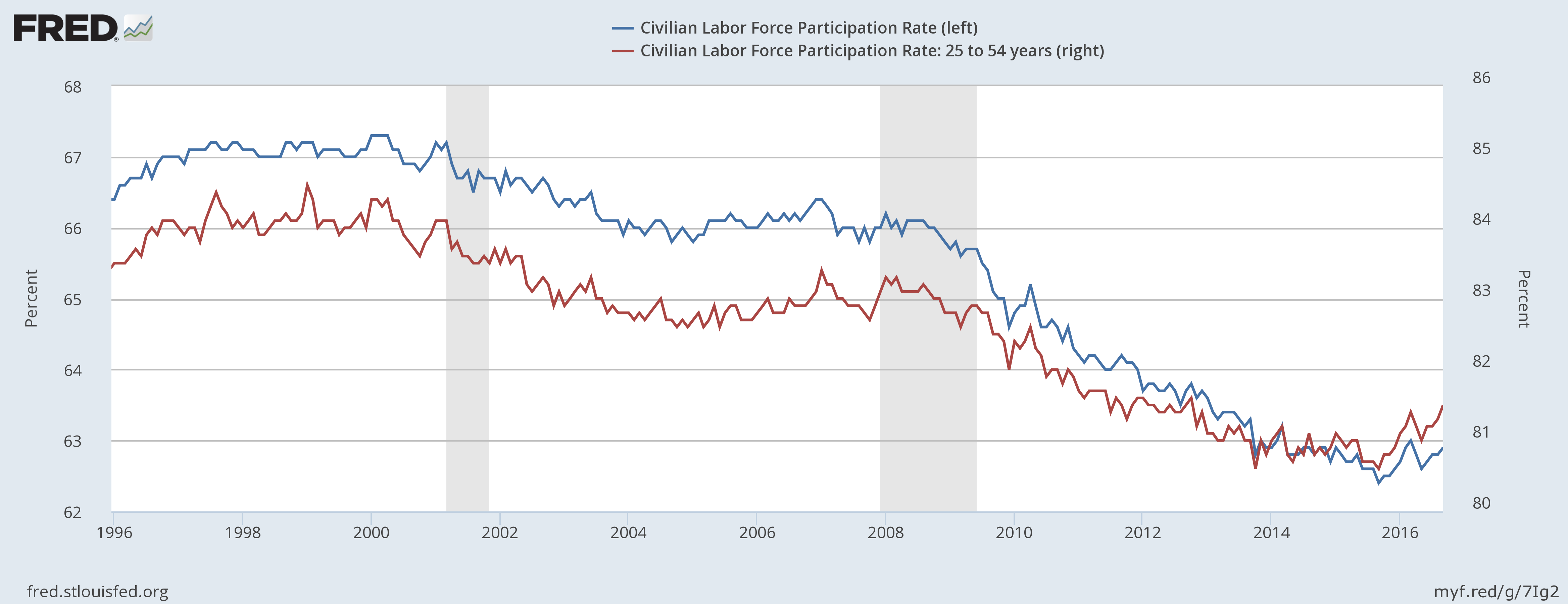

The clearest sign, though, that the economy isn't behaving like the Fed assumed it would might be the labor force participation, i.e. the portion of Americans who have a job or have looked for one in the last four weeks. After both the recessions of 2001 and 2008, the rate of participation collapsed. Some of that collapse is undoubtedly due to demographics: Retirees who are unlikely to ever re-enter the labor force have swelled as a portion of the population. But labor force participation for people age 25 to 54 — which doesn't include retirees or people in school — also collapsed and it's only just now trending back up. The participation rate for all ages has also finally stopped falling, and may be ticking up as well. (Note in the graph below that the age 25-to-54 participation rate, naturally higher than the rate for everyone, is measured on the right y-axis, while the rate for everyone is on the left.)

This backs up the case made by the doves at the Fed, that the unemployment rate downplays how many people could yet be drawn back into the workforce before inflation starts rising again. In fact, most all of the crazy stuff going on in the economy can be explained by the very simple thesis that the economy is still a long way from recovery.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The problem seems to be that many Fed policymakers and their allies just refuse to believe it.

Jason Furman, the chairman of the White House's Council of Economic Advisors, recently put out a paper on the conventional wisdom by which congressional economic policymaking has operated in recent decades: That the Fed's monetary policy is by far the best tool for fighting recessions and encouraging full employment, and that deficit spending by Congress is overwhelmingly likely to be ill-timed and ineffective, so Congress should just focus on balancing the budget.

Furman argues this consensus is on the ropes, with a new story — that deficit spending is often beneficial for the economy, and the room to deficit spend is far larger than realized — competing for attention. And again, the data backs up this new story. Furman documents rounds of recent studies that find fiscal stimulus can not only create and juice aggregate demand, but also encourage further private investment to flood in to the economy.

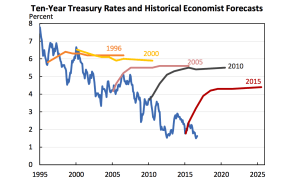

But perhaps most telling is the long collapse in interest rates, particularly on U.S. debt, which has been happening for decades. And which policymakers have repeatedly — and wrongly — insisted would reverse itself.

(Graph courtesy of Jason Furman, Chairman, Council of Economic Advisers.)

This is a sign, not of an economy at the peak of its powers, but of an economy where an enormous surplus of capital can find nothing useful to do. It can't be chalked up to Fed policy, as the Fed's share of U.S. treasuries is falling. A weak economy combined with basement-level interest rates isn't supposed to happen according to the old stories; the low interest rates are supposed to incentivize the investment that drives the recovery, which then drives interest rates back up. Yet that's the situation. The only remaining possibility is that what we're seeing is effectively a demand from the financial markets for the government to step in and deficit spend to create the new economic growth the markets can't generate on their own.

Really, the Fed's problem and the broader problem Furman notes are two sides of the same coin: If the economy was operating the way deficit hawks say it does, the stance of the Fed's inflation hawks would make sense. And vice versa.

But the story that the deficit hawks want to tell — even if it was true at one time — certainly isn't true now. The tectonic plates of the economy have shifted.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy