The Electoral College revolt will fail. But the rebellion is still worth it.

The risks of staging an Electoral College coup are big. But the payoffs could be much bigger.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Monday, the 538 members of the Electoral College will gather in each of their respective states to formally pick the next president of the United States. Donald Trump, who won states with 306 electoral votes, will almost certainly get more than the 270 required to be president, and then Congress will ratify his final electoral tally on Jan. 6, 2017.

He is going to be America's 45th president. Anyone who hopes otherwise is deluding themselves. Because even if the electoral coup succeeded (it won't), and electors denied Trump the 270 votes he needs (they're not going to get close), the decision on America's next president would get thrown to Congress. That's right, the Republican-controlled Congress. They would pick Trump, obviously.

But here's the thing: Electors should revolt against Trump anyway.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why stage an electoral coup that would ultimately fail? Two reasons: America is mature enough now to elect presidents by popular vote, and these rogue electors might be the only chance we have to scrap the Electoral College; and Trump needs more checks and balances than most presidents, and putting his fate in the hands of Congress would give Congress leverage.

Calls for scrapping the Electoral College aren't new. In 1969, the American Bar Association called it "archaic, undemocratic, complex, ambiguous, and dangerous." The system was created in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention as "a compromise meant to strike a balance between those who wanted popular elections for president and those who wanted no public input," The Associated Press notes. The only eligible voters at the time were land-owning males, and black slaves were enshrined in the Constitution as three-fifths of a person. AP continues:

At the time, the country had just 13 states, and the founders were worried about one state exercising outsized influence. Small states didn't want states with big populations to dominate. Southern states with slaves who couldn't vote worried that Northern states would have a louder voice. There were concerns that people in one state wouldn't know much about candidates from other states. The logistics of a national election were daunting. The thinking was that if candidates had to win multiple states rather than just the popular vote, they would have to attract broader support. [Associated Press]

Most of those reasons are outdated, AP notes: "The U.S. now manages to run national elections quite well. Voters nationwide have no shortage of information about candidates. Slavery no longer exists." John Adams, America's second president, was aghast at the idea of letting the commoners elect a president, but presumably we've come a long way since 1776. The framers of America's Constitution never envisioned a popular vote, which is why they created "the Electoral College as a deliberative body chosen by state legislatures," says E.J. Dionne at The Washington Post. "So what we are doing now is neither fair nor in keeping with the founders' vision."

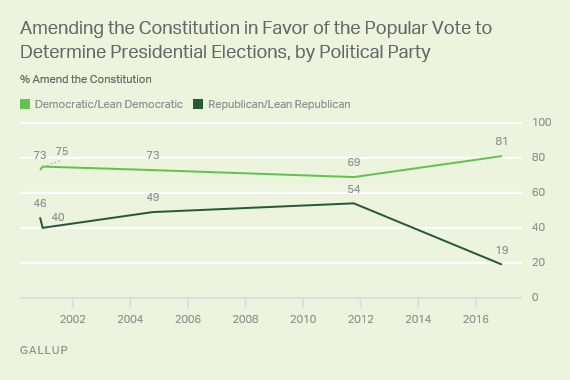

And the Electoral College isn't popular. Sizable majorities of Americans have supported repealing it every year Gallup has asked dating back 49 years — except in 2016, after Trump's election. A 49 percent plurality of voters still wanted to move to a popular vote, while 47 percent wanted to keep the Electoral College, but there was a huge partisan split:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Demonstrating the downside of giving a quasi-democratic "college" of party insiders final say over the presidency might sour the GOP's newfound love for the Electoral College.

If the 2016 electors are America's best hope to zero out their own power to pick a president, why would they risk public outrage and jail to burn the system down and spark rioting in the streets, especially since Trump would still become president? Leverage.

Trump is already setting up power struggles with Congress, and if there's any president concerned Americans want checked and balanced by people with experience in government and some fealty to the institutions and traditions of federal governance, it's Donald Trump. And if you don't think an impatient, imperious, famously litigious business tycoon who enjoys humiliating anyone who gets in his way will adopt an expansive theory of executive power, what election campaign did you watch? Trump's entire mystique stems from him sitting in a reality TV corporate boardroom set and firing people at his sole discretion.

But Trump understands power, and he has a lot of experience with negotiation. If the election is thrown to the House, Trump does not become president unless Speaker Paul Ryan and his fellow Republican members of Congress agree to it. At the very least, Trump would then owe the House a big favor. It's not impossible to imagine Trump being forced to agree to certain norms of behavior, and if he doesn't keep his end of the bargain, the House could pretty easily find grounds for impeachment in Trump's lawsuits and business conflicts of interest.

The end result is the same: Trump will be president. It is probably a ludicrous liberal fantasy to think otherwise. But it's certainly not crazy to imagine a scenario under which, when he takes office on Jan. 20, he will viscerally understand that there are three co-equal branches of government — or to hope that electors might push America to hate, with bipartisan fervor, the quixotic and antiquated system that put Trump in office.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.