Trump's path to power

Donald Trump may be the most unusual president Americans have ever elected. Armed with a keen sense of branding and a fierce will to win, he loves to defy norms, expectations, and critics.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From his picture window overlooking New York's Central Park, Donald Trump could see the public ice rink that the city government had spent six years and $12 million trying — and failing — to repair. Most people saw the shuttered rink as a maddening waste of public dollars. Trump saw an opportunity to lead.

In 1986, Trump, then a brash newcomer in New York real estate, offered to fix the rink in six months at his own expense. Trump's move was at once bold, magnanimous, and biting. In the same letter in which he made his offer to New York Mayor Ed Koch, Trump reminded the mayor that the "incompetence" the city had demonstrated in the rink project had to be "one of the great embarrassments of your administration."

Trump got the job done two months ahead of schedule and $800,000 under budget. The city paid for the work, but Trump slapped his name all over the place and generated months of adoring press. For decades to follow, the story of how he swooped in like Superman became a bedrock foundation of the Trump mythos, his carefully polished narrative of the billionaire who led by smashing through rules and expectations.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The man who has now moved from his very own gilded skyscraper on Fifth Avenue to noticeably smaller and less lavish quarters in Northwest Washington is the most unusual leader Americans have ever elected to manage their nation. He is a salesman, not a diplomat; a master marketer, not a bureaucratic manager. He is an entrepreneur who has always thrived on controversy and confrontation, bucking up against the establishment types who often sneered at him.

As president, Trump seems eager to lead in much the same ways as he has through four decades as frontman for his personal brand.

Trump brings to Washington a leadership style built on his father's success in the rough-and-tumble world of developing apartment buildings in New York's outer boroughs, and refined under the tutelage of Roy Cohn, the infamous Manhattan lawyer who taught young Donald that all publicity is good publicity and that victory comes only to those who fight back a hundred times harder than any hit they might absorb.

Trump built a real estate empire that morphed into a casino gambling business, which largely failed, driving the struggling mogul to pivot into a period of leasing his name to all manner of luxury and not-so-fancy products. Through it all, Trump spent much of his time not on the finances of his initiatives or on their daily management, but rather on cultivating his own image as a playboy billionaire who was bluntly decisive, refreshingly impolitic, and singularly devoted to all things Trump.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He rewarded loyalty (he called himself "a loyalty freak"), summarily sacked those who showed him up, and won fame and sometimes fortune as he put himself center stage in all his enterprises. "The show is Trump and it is sold-out performances everywhere," he said in 1990, soon after he appeared on the cover of Playboy.

The show — Trump has often called himself a "ratings machine" — is very much at odds with the private nature of the man, a loner who says he has few, if any, close friends, an insomniac who often leaves social events as quickly as possible, returning to his apartment to watch TV by himself through the small hours of the night.

In public, though, Trump is all business and all show, blending the two in ways that have now shattered the boundary between politics and celebrity.

As he launched his career in real estate, Trump broke with his father, who had warned him against taking on debt or working in the tough market of Manhattan. Donald longed to reach for the next level and build in midtown, and he did it by creating a business that looked bigger, bolder, and brasher than the competition. He led that business into the big time with tough, loud, showy tactics that he would hone through the decades.

Trump led by creating an image of himself as a rich playboy with fabulous connections — and by parlaying that image into actual deals with the city's rich and powerful. He led by making competitors, regulators, and bankers believe he was further along than he really was. And he led by neutralizing or even winning over his opponents by attacking, threatening, wooing, and even hiring them.

During his very first project, the rehab of New York's decrepit Commodore Hotel in the mid-1970s, Trump persuaded a New York Times reporter to write about him as "a major New York builder," though he had never built a thing and had no financing. Trump needed top New York politicians' cooperation to get his hotel project underway, and so he hired Gov. Hugh Carey's chief fundraiser, who had key political connections. It didn't hurt that Trump and his father had donated more money to the governor's campaign than anyone but the candidate's brother.

In the push for the same project, Trump sought a tax exemption from a state authority created to build racially integrated housing. The agency's chairman, Richard Ravitch, had grown up in the real estate business; Trump's father had hired Ravitch's father's construction firm to build the older Trump's largest apartment complex. Now Donald met with Ravitch and told him, as Ravitch recalled, "I want you to give me a tax exemption."

Ravitch declined. Trump repeated the request, and when Ravitch declined again, Trump said, "I'm going to have you fired." Trump, in an interview last summer, denied that account and called Ravitch "a highly overrated person."

Trump wasn't done. When city politicians who were opposed to the tax incentive called a news conference outside the shuttered hotel, Trump showed up and threatened to abandon the project if the city didn't give him tax relief. Trump had prepared for the event by directing his workers to replace the clean boards over the once-grand hotel's windows with dirty scrap wood, dramatizing the state of the midtown eyesore. The theatrical flourish had the desired impact. Trump got the exemption.

For four decades, Trump led his business empire through triumphs and disasters, through domination of the Atlantic City casino world and through six corporate bankruptcies, devoting his time and energy perhaps above all to his dealings with the news media.

The "key to the way I promote is bravado," he wrote in his best-selling book Trump: The Art of the Deal. "I play to people's fantasies. People may not always think big themselves, but they can still get very excited by those who do. That's why a little hyperbole never hurts.... I call it truthful hyperbole. It's an innocent form of exaggeration — and a very effective form of promotion."

In business and in the 2016 campaign, he alternately bashed reporters and privately treated them to praise and access. "From a pure business point of view," he wrote, "the benefits of being written about have far outweighed the drawbacks.... Even a critical story, which may be hurtful personally, can be very valuable to your business."

His longtime construction executive Barbara Res said, "Donald had a way of getting to print whatever he would say, even if it wasn't necessarily the whole and honest truth. He managed to say what he would say, and people would write it, and then it would be the truth. That was the thing with him that they call the big lie. You say something enough times, it becomes the truth."

Trump has refined the art of working the levers of public opinion to pressure those who would block his initiatives. In 1985, after he bought the Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida, Trump broke with the traditions of the wealthy enclave by chopping down his hedges to give gawkers a clear view of his castle, inviting a raft of celebrities and paparazzi, and opening the facility for wedding and event rentals.

The town council, annoyed by the increased traffic and attention, tried to impose restrictions on street use and party attendance. Trump responded by sending council members classic movies about discrimination — Gentleman's Agreement, about anti-Semitism, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, about racism — to remind them and the public about how the town had long tolerated the exclusion of Jews and blacks from private clubs in Palm Beach.

The effort to embarrass the politicians into easing restrictions on his club was successful.

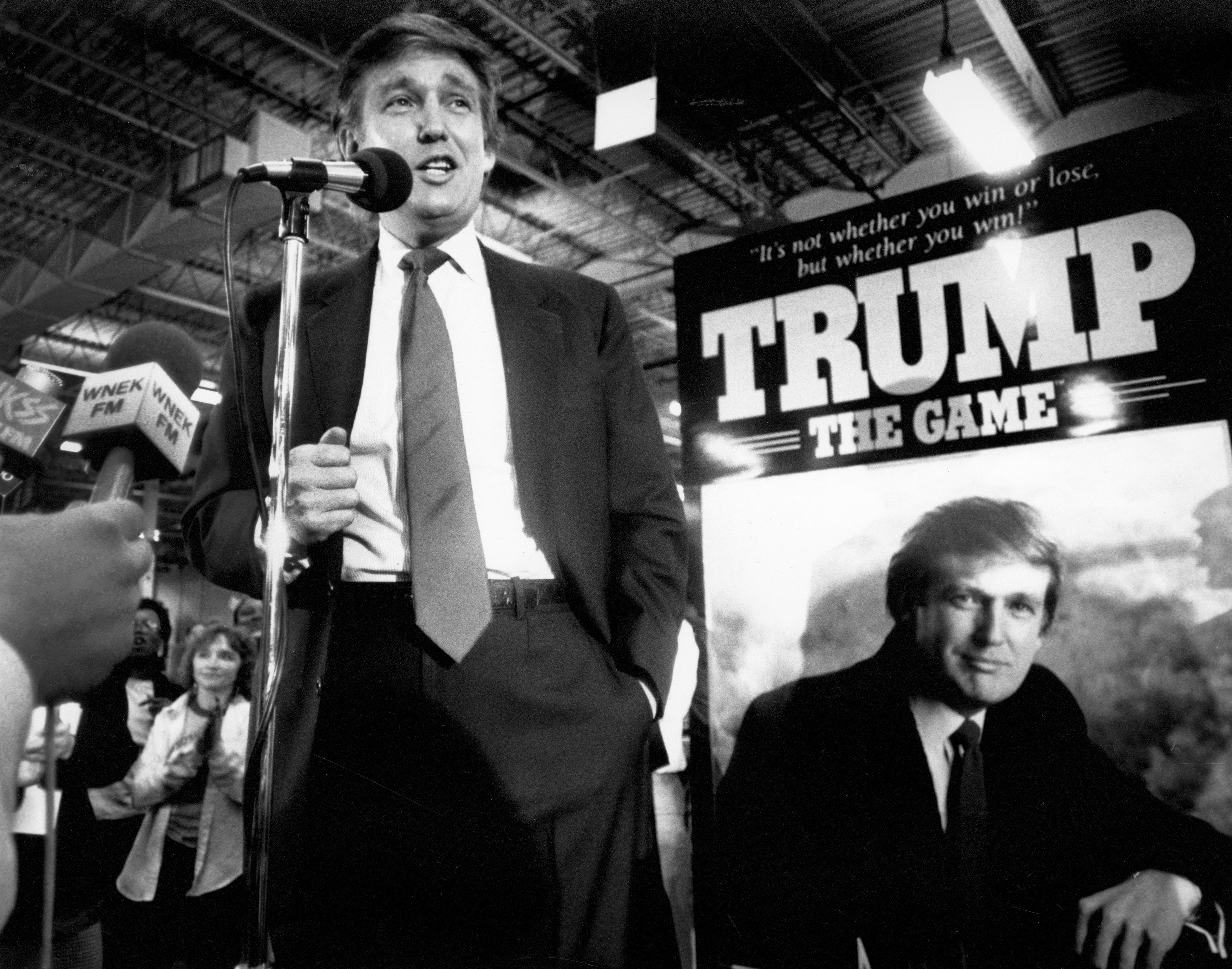

He recognized early on that his primary talent lay in marketing his brand, more than in managing day-to-day operations. In 1988, when Jeffrey Breslow, the inventor of many successful board games, visited Trump to pitch him on a Monopoly-like game that would be named after him, the game developer was prepared to get down on the floor and demonstrate how Trump: The Game was played.

But Trump had no interest in the details of the game. "I like it — what's next?" Trump said, and after the deal was negotiated, Trump volunteered to hold a press event at the plant where the product would be manufactured. His best value, he said, was in motivating the workers and winning media attention.

Trump has always measured success by the reach and power of his reputation and image. All of his ventures, in gambling, sports, TV, and politics, were designed to spotlight the message that "Trump" means ambition, wealth, and success.

He has always worked with a tiny inner circle of top executives — his campaign staff was about a 10th the size of Hillary Clinton's — remaining loyal to those who play by his rules: No one steps out on their own, all credit goes to the boss, and the message to the public is that Trump — the man, not the corporation or its other executives — is the rainmaker.

If Trump believes an executive has done something behind his back, he pounces: "You have to realize that people — sadly, sadly — are very vicious," he told an audience at a motivational seminar in 2005. "When a person screws you, screw them back 15 times harder."

He hires for loyalty but also to build a staff that looks the part — a factor he has often mentioned through the years, including during this winter's transition, when he would comment to aides about whether job candidates presented themselves in ways that would convince a TV audience that they were right for the job.

But Trump's methods for picking people can also be more subtle. Throughout his career, he has hired people who had been obstacles to his projects, both to neutralize their opposition and take advantage of their knowledge. Trump also hires to create rival power centers. Many GOP leaders thought Trump would have to choose between Republican National Committee chairman Reince Priebus and former Breitbart News chairman Stephen Bannon to set the tone for the leadership of his White House. But Trump hired both men — the establishment choice and the rogue outsider — and gave them equal billing in his hiring announcement.

When a group of tech executives visited with Trump in December, he told them: "You'll call my people. You'll call me. It doesn't make any difference. We have no formal chain of command around here."

Building such uncertainty and unpredictability into his leadership and decision making allows Trump to float possibilities, test ideas, and remain antagonistic to the powers that be — all before he puts a decision into play. Add his infamous lack of impulse control, in his predawn tweets, his thin-skinned reaction to criticism, his insulting comments about people he's already defeated, and a short attention span — he said he has no patience for reading reports or briefings — and the result is something not quite like any previous occupant of the White House.

He scoffs at deep study and goes, instead, with his gut. He believes in his instincts. He believes he will naturally do the right thing. He believes, as he wrote in his book Think Like a Billionaire, that "a narcissist does not hear the naysayers. At the Trump Organization, I listen to people, but my vision is my vision."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred